The French 18th-century chemist Antoine Lavoisier is a complicated historical figure. Scientifically, of course, he is an undisputed giant, helping usher in the chemical revolution as the field shifted from a qualitative to a quantitative approach, among many other achievements. He was also a wealthy nobleman and tax collector for the Ferme Generale, one of the most hated bodies of the Ancien regime as the French Revolution gained momentum. Those activities added to his fortune, which he used to fund his (and others’) scientific research and to foster public education. But it’s also why he ran afoul of the revolutionaries in power during the infamous Reign of Terror; they beheaded both Lavoisier and his father-in-law on the same day in 1794 as “enemies of the people.”

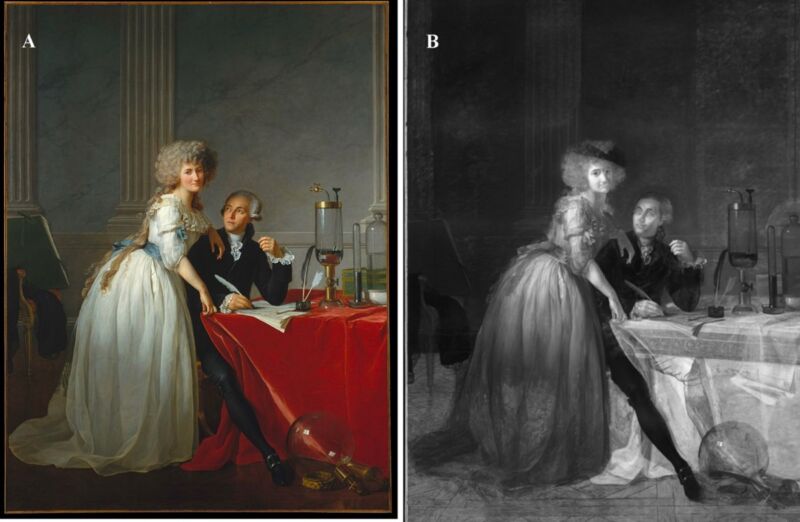

Something of that complexity is evident in a new scientific analysis of the famous 1788 portrait, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, of Lavoisier and his wife, Marie-Anne, by the Neoclassical painter Jaques-Louis David. The painting shows husband and wife posing with a collection of small scientific instruments—a tribute to their intellectual endeavors.

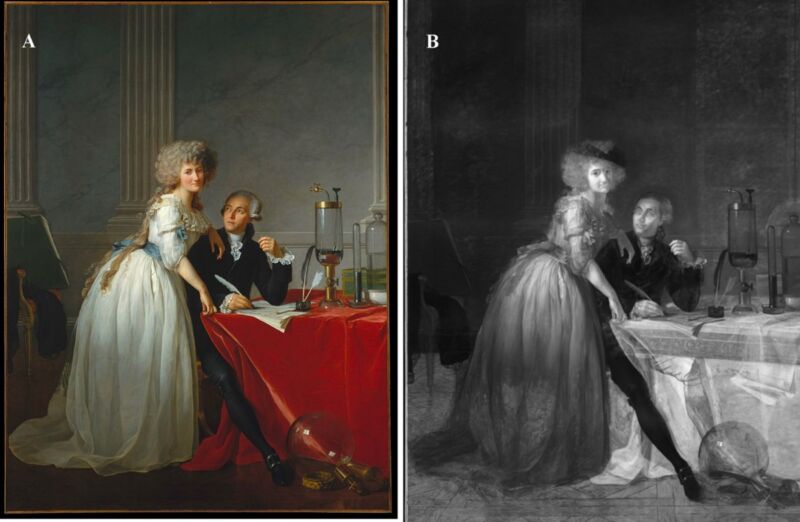

But cutting-edge analysis techniques have revealed that David originally painted a different version, without the scientific accoutrements, depicting the couple as more typical French aristocrats. He cleverly obscured the underpainting in the final portrait, most likely in response to the growing backlash against the aristocracy, according to a recent paper published in the journal Heritage Science. As the authors wrote in an accompanying online article for the Met: