Toned hamstring muscles provide shapeliness to the rear thighs, something that will be more visible this summer when you hit the beach or incorporate shorts into your wardrobe. However, many women – even those who work out regularly – don’t devote as much effort to their hamstrings as they do to their quadriceps – and it shows. Weak hamstrings will take away from your overall shape and figure. Unfortunately, it’s possible to have beautifully toned quadriceps from doing countless hours of squats or leg extensions, but possess unsightly hamstrings. This is usually the result of throwing in a couple of lying leg curls at the end of a quadriceps session, when your energy level is approaching zero. The best approach to having sexy, well-toned legs is to change your training day to a non-quad day and begin to spend some time and attention to the backs of your legs.

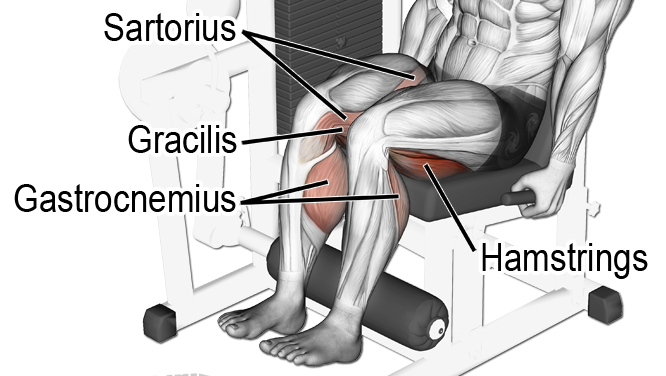

Muscles of the Posterior Thigh

The hamstring muscles consist of three muscles and part of another. The long head of the biceps femoris, semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles make up the bulk of the hamstrings, but the hamstring part of the adductor magnus is also an important accessory muscle to the major players.

The biceps femoris muscle is a two-headed (“bi”) muscle that lives on the posterior thigh (“femoris”; the femur is the thigh bone). It actually resembles the more familiar biceps brachii of the arm in general structure. The long head of the biceps femoris attaches to the ischial tuberosity on the posterior side of your hip structure. The ischial tuberosities are the bony parts that you sit on when you’re in a chair. The fibers of the short head of the biceps femoris begin on the lower one-third of the femur bone, just above the knee. Because they don’t attach to the ischial tuberosity and thus, don’t cross the hip joint per se, the short head isn’t considered to be a true “hamstring” muscle (but it has the same function at the knee as the other hamstring muscles). Both heads of the muscle fuse into a thick tendon, which crosses to the lateral side of the knee joint to attach to the fibula bone (and some ligaments) on the knee.

The semitendinosus muscle is part (“semi”) tendon (“tendinous”) and part muscle. The semitendinosus fibers attach to the ischial tuberosity and insert into a cord-like tendon about two-thirds of the way down the posterior thigh. The semitendinosus muscle crosses the knee joint posteriorly to attach to the medial side of the superior part of the tibia (the large medial bone of the leg). The semimembranosus muscle is partly (“semi”) membrane (“membranous”) and partly muscle. It begins on the ischial tuberosity of the hip and attaches to the posterior part of the medial condyle of the tibia just below the knee joint. The adductor magnus muscle primarily acts as a thigh adductor and it pulls the thigh close to the midline of the body. However, a vertical portion of the adductor magnus is called the “hamstring part” because it attaches on the ischial tuberosities and runs to the adductor tubercle on the femur. The adductor tubercle is a small prominence of bone just above the knee joint on the femur.

“True” hamstring muscles cross both the knee and the hip joints posteriorly. With this arrangement, they can both extend the thigh at the hip joint (i.e., it helps to draw the thigh posteriorly as when sprinting) and flex the leg at the knee joint (bringing the heel toward the buttock). The short head of the biceps femoris only flexes the knee, and the hamstring part of the adductor magnus only extends the thigh at the hip joint.

Seated Leg Curls

It’s difficult to activate both functions of the hamstrings in a single exercise. To get around this problem in the leg curls, the hip joint on one end of the muscle is fixed so that the muscle group is stretched, while the knee is allowed to move. Leg curls can be done standing, lying prone on your stomach, or seated. The seated version fixes the hip joint so that the knee joint is free to move. This exercise is a rather strict version of the leg curl; much like concentration curls are to the biceps brachii muscles of the arm.

1. Position yourself on a seated leg curl bench. Adjust the back pad so your knees clear the front edge of the seat. The angle of rotation on the thigh bar should be at the center of the lateral side of your knee joint. Set the thigh-stabilizing pad across your thighs, and make sure it’s not across your knees. In this position, the knee should be able to move freely. The hips will be in a flexed position because you’re in a seated position, so the knee flexion function of the posterior thigh and hamstring muscles will be activated.

2. Adjust the position of the ankle roller so it sits just above your heel, over the Achilles tendon.

3. Hold the hand grips to help to keep your upper body and hips in the proper position.

4. Start with your knees straight (or perhaps just slightly bent). Take a breath, then exhale as you flex your knees past 90°. Try to imagine that you’re trying to flex your knee with the intention of touching your seat with your heels. Keep your hips on the bench and don’t let them lift upward during this exercise.

5. Hold the flexed position for a count of two, then inhale as you slowly lower the legs to the starting position. Don’t straighten your knees completely or let the weight stack touch as it’s going down. Immediately after reaching the end of the repetition, begin the next repetition.

If you want to turn the heat up a bit (particularly during the last two sets of the exercise), try plantarflexing your feet by pointing your toes downward as you flex your knees. The ankle position has no direct effect on the hamstrings, as their distal attachment is at the knee and not the foot/ankle. However, plantarflexion decreases the effectiveness of the gastrocnemius (calf) muscles, which are able to contribute to knee flexion. This will make it much harder to flex your knee when the gastrocnemius muscles are functionally removed in this manner. However, it will really start to shape your posterior thigh and be more effective than if you didn’t plantarflex the ankle. Be aware that this isn’t an easy adaptation and in fact, can be downright painful after a few repetitions.

Stretching the hamstrings between sets is very important, as this should minimize the chances of obtaining back injures or pain resulting from having hamstrings that are too tight. Lock your knee(s) out straight and slowly pull your chest toward your thigh by flexing the trunk. Try to avoid straining your neck to do this. Hold each stretched position for at least 10 seconds, and repeat at least twice before moving to the other leg.

The hamstrings can be boring to train, and it’s hard to see the muscles contract when you’re training them, but never use these excuses to avoid hamstring work. This just means that you’ll have to concentrate and focus more on this exercise than some others. You must engage your mind and focus on performing this exercise strictly and correctly. It’s too easy to lift your hips, or move the ankles from plantarflexion into dorsiflexion as this will bring other muscles into play, so it’s important that you do the exercise strictly and under full control. Nevertheless, if you have the determination and dedication to do it right, then seated leg curls may be just the ticket you need to shape and tone the backs of your legs. It may take a few months before you notice any dramatic differences, but if you’re willing to pay your dues, your hamstrings will be the envy of the gym. With toned rear thighs you won’t look one-dimensional, and your lower body will look sexy, sleek and buff.

References:

1. Andersen LL, Magnusson SP, Nielsen M, Haleem J, Poulsen K and Aagaard P. Neuromuscular activation in conventional therapeutic exercises and heavy resistance exercises: implications for rehabilitation. Phys Ther, 86: 683-697, 2006.

2. Brockett CL, Morgan DL and Proske U. Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 36: 379-387, 2004.

3. Decoster LC, Cleland J, Altieri C and Russell P. The effects of hamstring stretching on range of motion: a systematic literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 35: 377-387, 2005.

4. Hopper D, Deacon S, Das S, Jain A, Riddell D, Hall T and Briffa K. Dynamic soft tissue mobilisation increases hamstring flexibility in healthy male subjects. Br J Sports Med, 39: 594-598, 2005.

5. Moore, K.L. and A.F. Dalley. Clinically oriented anatomy. 4th Edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. P.J. Kelly, Editor, 1999: pp. 550-575.

6. Proske U, Morgan DL, Brockett CL and Percival P. Identifying athletes at risk of hamstring strains and how to protect them. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 31: 546-550, 2004.

The post Toned and Shapely Leg Workout first appeared on FitnessRX for Women.