Washington and Tehran will meet indirectly in Austria next week as part of a gathering to keep the Iran nuclear deal alive.

After months of nearly no movement, the US and Iran will finally have their first real chance to revive the 2015 nuclear deal next week.

On Tuesday, officials from Iran, the European Union, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany will meet in Vienna, Austria, to discuss how the US — which withdrew from the multilateral nuclear accord in 2018 under President Donald Trump — can return to the pact known officially as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). It’s a deal many would like to keep alive since it severely curbs Iran’s nuclear development in exchange for sanctions relief.

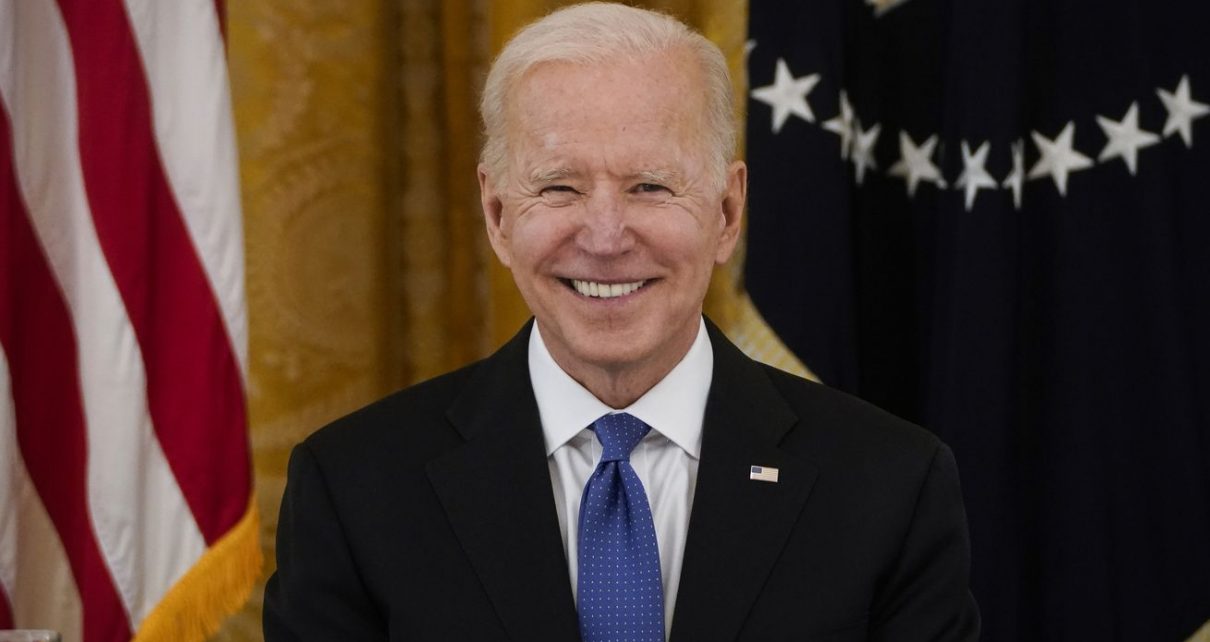

State Department spokesperson Ned Price confirmed to me that the US will be in attendance “to identify the issues involved in a mutual return to compliance with the JCPOA with Iran,” he said. Officials from President Joe Biden’s administration won’t speak directly to the Iranians, but they will meet the other parties.

“The primary issues that will be discussed are the nuclear steps that Iran would need to take in order to return to compliance with the terms of the JCPOA, and the sanctions relief steps that the United States would need to take in order to return to compliance as well,” he continued, adding “we don’t anticipate an immediate breakthrough … but we believe this is a healthy step forward.”

Analysts agree. “It’s promising that experts groups will be meeting to discuss the key issues of sanctions relief and nuclear rollback,” said Eric Brewer, an expert on Iran’s nuclear program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, “but I’d caution that we’re not out of the woods yet.”

The Iran deal is on life support. This meeting may help bring it back to life.

Next week’s session, first reported by the Wall Street Journal, is a big deal and comes after months of posturing by Washington and Tehran.

At the heart of the Iran deal was a simple trade: Tehran would severely restrict its nuclear development in exchange for much-needed sanctions relief from the US and other signatories. But the US broke the pact and reimposed its sanctions after the Trump administration three years ago, leading to a dramatic collapse of Iran’s economy made worse by the pandemic.

In response, Tehran violated its terms as a pressure tactic. Among the provocative moves, Iran began enriching uranium at levels beyond caps outlined in the accord.

That led to a standoff after Biden entered office. Even though the new administration signaled a desire to return to the deal, they said Iran would receive no sanctions relief until it came back into compliance with the agreement. Tehran, meanwhile, said the US had to lift the financial penalties first both as a sign of goodwill and out of fairness since Washington withdrew from the accord.

Biden’s team made multiple efforts to break the deadlock.

In February, for example, Washington accepted an offer to hold informal talks with Tehran brokered by the European Union. But Iran rejected the opportunity, with one official saying the “time isn’t ripe for the proposed informal meeting.”

And last month, according to Politico, the US proposed that Tehran stop enriching uranium and halt work on advanced centrifuges in exchange for partial sanctions relief. But once again, Iran refused the offer.

All that bodes poorly for next week’s meeting, especially since the US and Iran won’t interact directly, a move Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif deemed “unnecessary.” Price, the State spokesperson, told me “the US remains open” to such direct chats.

What seems more possible is Washington and Tehran could leave Austria with a better understanding of how both sides expect the Iran deal’s revival to proceed.

“At this point, it sounds that they are less interested in initial gestures than in defining what a comprehensive return to compliance would look like,” an unnamed US official told the Wall Street Journal on Friday. “We have no problem with that as it is consistent with our own initial view.”

But even then complications abound, said Brewer, who worked on Iranian nuclear issues in the last administration’s White House.

“Think of it as two chunks of time. There’s the time it will take for the US and Iran to reach agreement on what constitutes compliance, the steps involved, and the sequence,” he told me. “And then once that is agreed, [there’s] the amount of time required to implement the plan.” Part of that implementation process involves verifying that Iran has in fact ended its nuclear advancements, and perhaps even a direct US-Iran meeting to finalize terms.

Put together, there likely won’t be an all-encompassing pathway forward agreed to in Vienna next week. But the talks could signal the end of the standoff and a beginning of the road back to the nuclear pact.