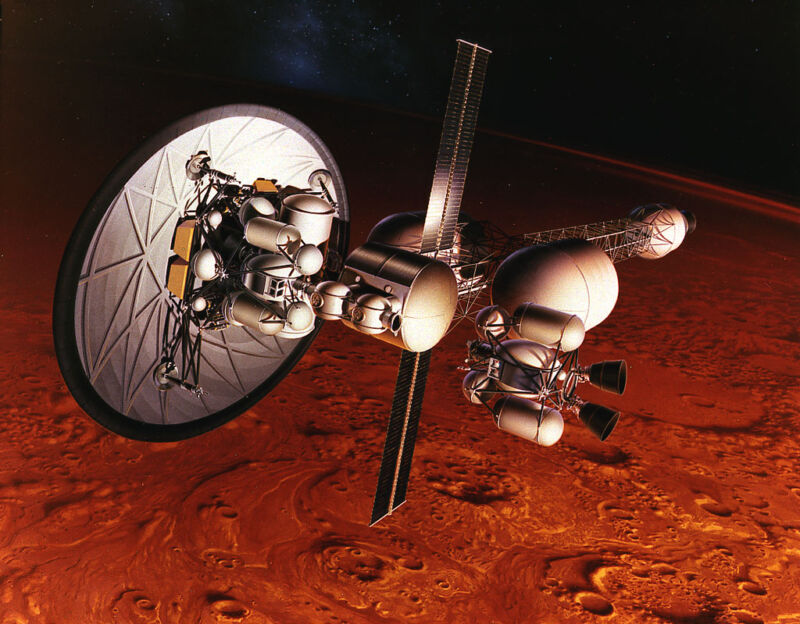

Enlarge / NASA originally studied nuclear thermal propulsion in the 1960s. Here is concept art for the Nuclear Energy for Rocket Vehicle Applications (NERVA) program. (credit: NASA)

Getting humans to Mars and back is rather hard. Insanely difficult, in fact. Many challenges confront NASA and other would-be Mars pioneers when planning missions to the red planet, but chief among them is the amount of propellant needed.

During the Apollo program 50 years ago, humans went to the Moon using chemical propulsion, which is to say rocket engines that burned liquid oxygen and hydrogen in a combustion chamber. This has its advantages, such as giving NASA the ability to start and stop an engine quickly, and the technology was then the most mature one for space travel. Since then, a few new in-space propulsion techniques have been devised. But none are better or faster for humans than chemical propulsion.

That’s a problem. NASA has a couple of baseline missions for sending four or more astronauts to Mars, but relying on chemical propulsion to venture beyond the Moon probably won’t cut it. The main reason is that it takes a whole lot of rocket fuel to send supplies and astronauts to Mars. Even in favorable scenarios where Earth and Mars line up every 26 months, a humans-to-Mars mission still requires 1,000 to 4,000 metric tons of propellant.