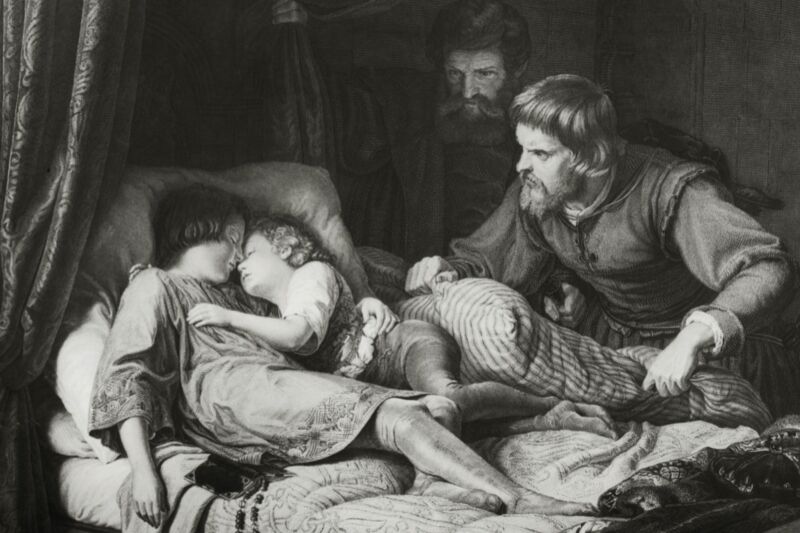

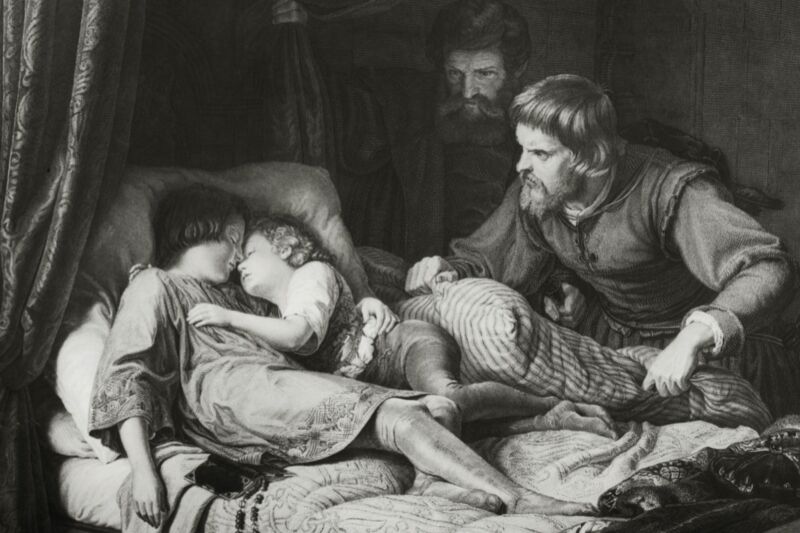

Enlarge / Vintage engraving (1876) depicting the murderers of the “Princes in the Tower”: King Edward V and his younger brother, Prince Richard, Duke of York. New evidence has emerged that Richard III did indeed order the murders. (credit: Getty Images)

England’s King Richard III is at the center of one of the most famous assassination legends in history, immortalized in one of William Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies. It’s quite the tale: a power-hungry duke seizes the throne when his brother unexpectedly dies, and he orders his young nephews (one the rightful heir) murdered in the Tower of London to cement his claim to the throne. But was he really a murderer? The debate over Richard III’s presumed guilt has continued for centuries. Now a British historian has compiled additional evidence of that guilt, described in a recent paper published in the journal History.

The so-called “princes in the Tower” were the sons (aged 12 and 9) of King Edward IV, who died unexpectedly in April 1483. Edward’s elder son and heir (now technically King Edward V) and the younger sibling (Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York) were originally brought to the Tower of London in May by their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, ostensibly to prepare for Edward’s formal coronation. But the coronation was postponed until June 25 before being postponed indefinitely. Gloucester assumed the throne instead as King Richard III, and he had Parliament officially declare young Edward and his brother illegitimate the following year.

Although no bodies were produced at the time, historians largely agree that the princes were likely murdered in late summer of 1483. Two small human skeletons were found at the Tower of London in 1674, but there is no conclusive evidence that these were the princes, despite a perfunctory examination in 1933 concluding that the remains were those of children roughly the same ages. Two more bodies that may have been the princes were found in 1789 at Saint George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. Forensic scientists have been unable to gain royal permission to conduct DNA and other forensic analysis on either set of remains in order to make a proper identification.