Our mission to make business better is fueled by readers like you. To enjoy unlimited access to our journalism, subscribe today.

U.S. President Donald Trump last week signed into law the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, allowing the U.S. to remove foreign firms from U.S. stock exchanges if they don’t comply with auditing requirements.

The legislation is aimed at Chinese companies. Its bipartisan sponsors—Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) and Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.)—say the law will protect Americans from being “cheated” and “exploit[ed]” when they invest in Chinese firms that trade on U.S. exchanges.

Before Trump signed the bill into law, it passed both the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives with unanimous support—a clear show of how anti-Beijing legislation has united Democratic and Republican lawmakers like little else has.

Subscribe to Eastworld for weekly insight on what’s dominating business in Asia, delivered free to your inbox.

A government watchdog earlier this month ranked this Congress, the 116th, the “least productive in history.” The COVID-19 relief deal that Congress struck on Sunday—and is now in doubt—is a prime example of the dysfunction; it took lawmakers eight months to find common ground. But legislation taking aim at Beijing’s growing influence has sailed through both chambers this year.

That’s because Washington “increasingly views all Chinese firms as arms of Beijing’s political and geopolitical ambitions,” said Michael Hirson, practice head of China and Northeast Asia at political risk consultancy Eurasia Group. “The reality is more nuanced, but subtleties are lost in the China debate today,” Hirson said, since Capitol Hill is now dominated by a “prevailing consensus about being tough with China.”

A “generational” shift

It wasn’t always this way.

For decades, the U.S.-China relationship has been one of general cooperation with periods of disagreement, says Dane Chamorro, partner at the Asia Pacific practice of risk consultancy Control Risks. The new normal is the reverse—”a largely contentious [relationship] with only episodic collaboration,” Chamorro said, calling the change a “generational” shift.

One reason for the evolution is China’s economic and technological progress that has made it more competitive with the U.S., says Hirson.

In the past few years, China has made advances in robotics, artificial intelligence, 5G wireless networks, and surveillance technology. Chinese companies like Huawei and Xiaomi dominate the global smartphone market, and China has emerged as a global leader in e-commerce, electric vehicles, and digital payments.

“The tensions that we see now in capital markets, including the delisting issue, is driven in part by the tech rivalry and [U.S.] concerns about funding China’s next-generation national [tech] champions,” Hirson said.

On Dec. 3, a day after the U.S. House of Representatives passed the delisting bill, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying called the act a “concrete example of [U.S.] political suppression of Chinese companies in a bid to contain China’s development.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s promotion of “civil-military fusion,” a state-led initiative to increase collaboration between the private sector and China’s military, also “has fueled the narrative in Washington that all Chinese companies are arms of Beijing’s geopolitical aims,” Hirson said.

Then there’s the Trump effect.

On the 2016 campaign trail, Trump’s message was rife with harsh criticism of China. As President, he packed his administration with “China hawks,” officials and advisers who deem China a threat to the U.S. and advocate policies to counter that perceived threat.

The Trump administration has pursued a trade war with China; imposed visa restrictions on Chinese Communist Party affiliates, Chinese students, and Chinese journalists; and attempted to ban hugely popular Chinese-owned apps TikTok and WeChat.

The administration’s aggressive campaign against China has shifted the conversation in Washington, said Hirson. “Both parties in Congress are far less inclined than in the past to favor the interests of the business community in China over perceived issues of national security and ideological competition with Beijing.”

Chamorro argues that U.S. lawmakers’ souring attitude toward China predates the recent proliferation of China hawks in U.S. policymaking. He sees Xi as the main impetus. Ever since the Chinese President assumed office in 2012, he’s engaged in “a more aggressive foreign policy” than his predecessors. For instance, China laid territorial claims to disputed islands in the South China Sea, alarming U.S. lawmakers.

The monthslong protest movement in Hong Kong in 2019 that captured global headlines, and Beijing’s subsequent imposition of a controversial national security law in the territory, also deteriorated U.S.-China relations and solidified bipartisan consensus on China matters.

Bipartisanship on China

The cross-aisle determination to counteract Beijing was on full display during the 2020 presidential election, when each campaign tried to prove its “tough on China” credentials and paint the other as subservient to Beijing.

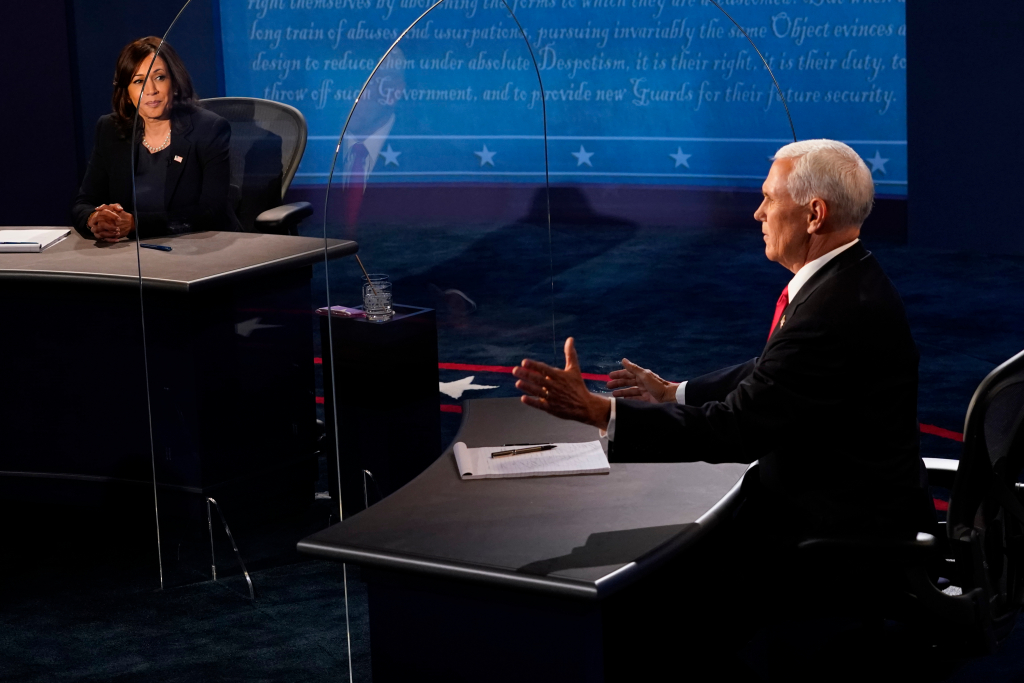

In October, during the vice presidential debate, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) accused the Trump administration of losing 300,000 U.S. jobs in the “so-called trade war with China,” and Vice President Mike Pence called Democratic nominee Joe Biden a “cheerleader for Communist China.”

Campaign ads carried similar messaging: A Trump spot said Biden “stands up for China,” while a Biden ad said Trump “rolls over for the Chinese.” Each ad featured an image of the rival candidate alongside Xi.

The campaign rhetoric is proof that even though U.S.-China relations sunk to their lowest point in decades under Trump, the bipartisan mood toward Beijing is unlikely to change when President-elect Biden assumes office in January, analysts say.

In addition to the delisting bill, other anti-Beijing pieces of legislation have passed Congress with similar levels of bipartisan support this year, especially bills related to Beijing’s tightening grip on Hong Kong and treatment of the Uighur ethnic minority in the Xinjiang region.

Earlier this month, a bill to expand U.S. refugee status to Hong Kong residents passed the House without opposition. In July, the Senate unanimously passed an act that sanctions Chinese officials Washington says have violated Hong Kong’s autonomy and penalizes financial institutions that do business with those officials.

In May, a bill that sanctions individuals and entities responsible for alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, where China’s government has been accused of surveilling and detaining Uighur people and other minorities, passed the Senate unanimously and then passed the House with just one dissenting vote. Trump signed the bill into law in June.

Clamping down on risk

At the same time, analysts say, lawmakers’ support for the delisting legislation stems from a real desire to protect U.S. investors from risk.

Under the new law, U.S. exchanges must delist firms that don’t provide the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) with audit reports for three consecutive years. The Chinese companies on U.S. exchanges that could be delisted have a combined market capitalization of $1 trillion, which represents around 3% of the total equity market cap in the U.S., according to a June report by investment bank China Renaissance.

The law applies to all foreign firms on U.S. exchanges, but it targets Chinese firms in particular because China’s state secrecy laws don’t let Chinese companies share certain financial information outside of China’s borders. The U.S. law also requires firms to disclose whether any of their board members are Chinese Communist Party officials.

Congress has pressed the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and PCAOB, which the SEC oversees, for years to reach an agreement with Chinese regulators that would allow the U.S. to review the audit papers of U.S.-listed Chinese firms, Hirson said. The new delisting law addresses this demand. In a political environment less hostile to Beijing, Congress may have pressured the SEC to take action on the auditing impasse “in a more gradual manner,” rather than through a law of its own, Hirson said.

When the bill passed the House on Dec. 2., bill sponsor Sen. Kennedy said in a statement that “U.S. policy is letting China flout rules that American companies play by, and it’s dangerous.” Fellow sponsor Sen. Van Hollen criticized “seemingly legitimate Chinese companies that are not held to the same standards as other publicly listed companies” in his own statement.

Both senators said the law would protect retirement savers from fraudulent companies, and Van Hollen said Americans who invest their retirement funds in U.S.-listed Chinese companies have been “cheated out of their money.” However, the risk to retirees is relatively small. Chinese equities and bonds accounted for 0.6% of total U.S. retirement assets under management in 2019, according to a May report from China Renaissance.

Bruce Pang, head of macro and strategy research at China Renaissance, argues that the risk of investing in Chinese firms listed on U.S. exchanges has stayed the same for years and the new restrictions are “more politically motivated.”

The law’s supporters argue that the lack of financial information about U.S.-listed Chinese companies puts U.S. investors with shares of these companies at risk. But existing SEC policy already makes investors aware of the limited transparency. It requires firms with operations in China to disclose to potential investors that American regulators can’t inspect audit papers in mainland China; firms must include it as a risk factor in their listing applications if they go public on a U.S. exchange.

Still, big scandals helped the delisting legislation gain traction; the Luckin Coffee saga was chief among them. In July, Nasdaq delisted the Chinese coffee chain after Luckin said an internal investigation had revealed substantial sales fraud.

The SEC is currently investigating New York Stock Exchange–listed Chinese education firm GSX Techedu for allegedly falsifying its sales. (GSX denied short-sellers’ fraud allegations and said it is cooperating with the SEC probe.) In November, San Francisco–based short-seller Muddy Waters Research—which shorted Luckin and GSX earlier this year—accused Nasdaq-listed Chinese media platform JOYY of fraud. (JOYY denied the allegations.)

U.S. exchanges are still attractive to many Chinese firms. But the new law is one more reason Chinese firms seeking capital may look elsewhere. “It increasingly makes less sense for Chinese firms to list in the U.S., particularly for firms in strategically important sectors such as technology,” Hirson said.

Because the new law can be framed as addressing U.S. national security concerns, and because of “the very real problem of lack of transparency” among many U.S.-listed Chinese companies, said Chamorro, “it’s something that, from a domestic political perspective, would be very hard not to support.”

More must-read stories from Fortune:

- Everything to know about the stimulus deal—including $600 checks and $300 unemployment benefits

- Biden wants to change how credit scores work in America

- COVID vaccine recipients may still be infectious. When will we know for sure?

- How Hawaii’s COVID-19 testing program could serve as the blueprint for a broader reopening of international travel

- Trump pardons: 7 high profile people who may get one