Before he became an international symbol, he played a common man whose outrage over corruption elevated him to high office.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy may have briefly made US headlines a couple of years ago when Trump was impeached for pressuring him to help with Trump’s campaign, but the vast majority of Americans (including me) would have struggled to identify him a month ago.

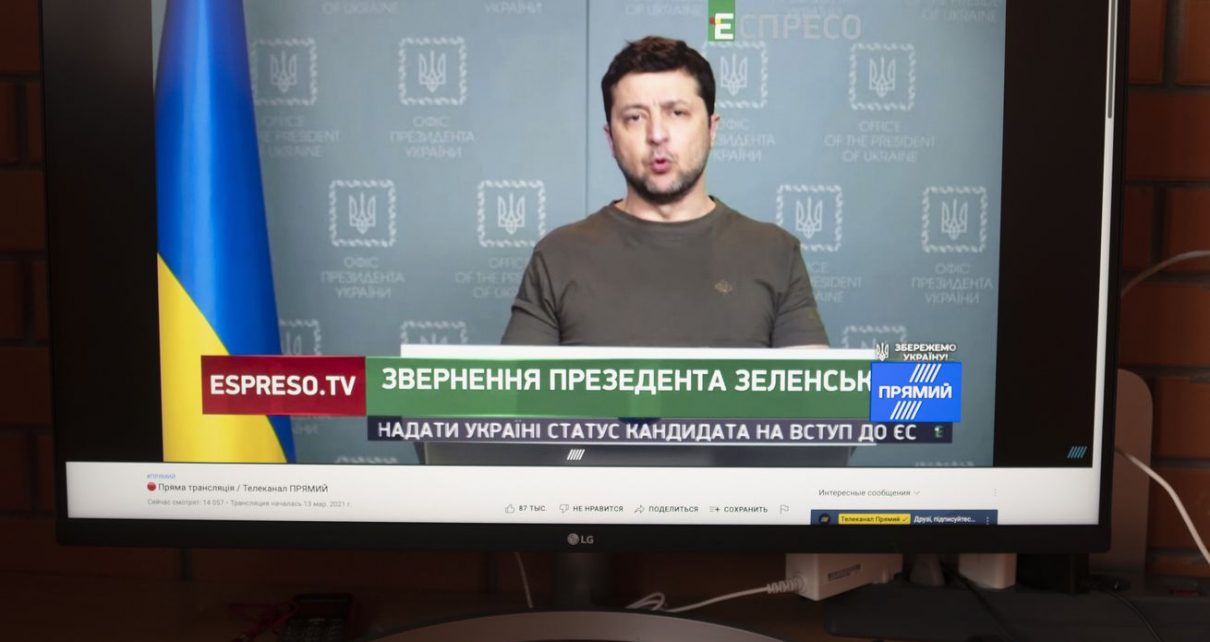

That changed when Russia invaded Ukraine and Zelenskyy made the high-profile decision to stay in Kyiv and fight for his country, releasing regular addresses to his people and making emotional appeals for the global aid that Ukraine needs to fend off the Russian assault.

When the US offered to evacuate him to safety, he refused, according to one unnamed US official, replying, “I need ammo, not a ride.” Every few days, rumors circulate that he’s fled; every time, he refutes them with a video taken at his presidential office or on the distinctive streets of Kyiv. Russia has reportedly tried to kill him repeatedly, and failed. According to one recent poll, he’s now the most popular politician among American voters — significantly more so than his counterpart in the White House.

No one expected this of Zelenskyy, who before his star turn on the world stage was an actor and a comedian. He became Ukraine’s president after playing Ukraine’s president on TV, in the comedy Servant of the People, which ran from 2015 to 2019.

But a close reading of that show offers a glimpse of Zelenskyy’s outlook toward moral courage, as well as a look at Ukraine’s national struggle and the cultural forces that shaped the nation now fighting for its survival.

In the show, Zelenskyy is a humble high school teacher whose rant about corruption goes viral on YouTube and propels him to the presidency. The show is on YouTube, and I’ve been watching it with my family since the war began. I’ve found it surprisingly moving: a funny, but fundamentally serious, meditation on how to do good in the world, saved from being corny or self-aggrandizing by the life-or-death reality that now frames it.

There’s always something salutary about watching another society’s political television, like the Danish political drama Borgen, or the thriller Occupied, about a soft Russian takeover of Norway. You can get a similar effect, albeit across time rather than space, by watching (or rewatching) older politically themed shows from the US.

Take a look at The West Wing these days and boggle, with two decades’ remove, at their heated debates over early ’00s issues like school prayer and whether Christians are oppressed in China.

We come into our own modern political debates with a strong sense of where the battle lines are drawn, which positions are reasonable, and which are unthinkable. Watching another country’s — or another time’s — television is a chance to break away from that, to get a glimpse of different sets of assumptions and where they might lead. We can come to understand that politics aren’t just about the issues, but about the systems in which they play out — and the people who make up those systems.

A servant becomes president

Servant of the People’s appeal isn’t its political sophistication (it is not politically sophisticated) or its witty West Wing-style dialogue. (The dialogue’s wit is mostly obscured for US watchers because there seems to be no particularly good English translation — the episodes on YouTube have fan-produced subtitles.)

What makes it work, instead, is its earnestness, its clarity: It is a story about what Ukraine, a country with a bloody history that is struggling toward democracy, wants to be, and the courage that will be required to get it there.

In the sixth episode of the show, the newly minted president reviews the budget and is appalled by the massive sums for luxuries for himself and all his top ministers. Fired up, he tells the prime minister that he thinks spending can be cut back 90 percent.

Meanwhile, his cab driver father and nurse-practitioner mother, who’ve lived their whole lives in poverty — like many in Ukraine, where the prewar per capita GDP was less than $3,800 — are redecorating their apartment with luxurious furniture and gold trimmings, delighted to finally get their turn at the honeypot.

When the president returns home to see the result, he realizes that corruption isn’t just about greed. It’s also motivated by a sense of deserving better and being finally powerful enough to reach for it — while forgetting that every other person in Ukraine deserves that, too. He says as much to his parents, storms out of the house, and ends up sleeping on a park bench. (Zelenskyy himself has run into some trouble on the issue, with reporting from the Pandora papers in 2021 connecting him to stakes in offshore companies; an adviser later said he used the connection to protect his interests against pro-Russia opponents.)

Absent the real-life context, this — and many moments on the show like it — would land as self-aggrandizing to the point of absurdity. But the facts on the ground today lend Servant of the People all the moral authority it could possibly want: The real Zelenskyy, no longer merely playing a leader on TV, remains in Kyiv, in grave danger.

The stubbornness and moral character Zelenskyy is now demonstrating on a daily basis is at the core of Servant of the People’s narrative. It depicts a Ukraine where ordinary, hardworking people endure constant humiliations and injustices, while the rich make themselves richer, not even thinking of themselves as part of the country they are bleeding dry.

And — airing, as it did, shortly after the 2014 revolution that installed a more Europe-friendly government — it depicts a Ukraine that is more than ready to change, to be fair, to be just, to be free, as long as one man wins the struggle within himself to fix what he could more easily be complicit in.

Mr. Zelenskyy goes to Kyiv

Ukraine, in voting Zelenskyy into office in real life with 73 percent of the runoff vote in 2019, overwhelmingly supported that story as their preferred narrative of the nation’s history and trajectory. If Ukrainians can hold off Putin’s forces and remain independent — and they genuinely might, hard as that was to believe even two weeks ago, and unlikely as it remains — it’s a story they (and he) will have made real.

And if they lose, the millions of Ukrainians who are unable to flee will fall under the control of a totalitarian state that has banned even discussing the bombs it is dropping on innocent people.

I recommend Servant of the People. The gorgeous blocks of Kyiv depicted in the show are, in many cases, no longer standing. The actor playing the lead character is now the real president of Ukraine and at real risk of death. And despite all that, or maybe because of all that, it’s some cheerful, optimistic television, at a moment when that is desperately needed.

A version of this story was initially published in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here to subscribe!