The US is rejoining the Paris climate accord and the World Health Organization on day one.

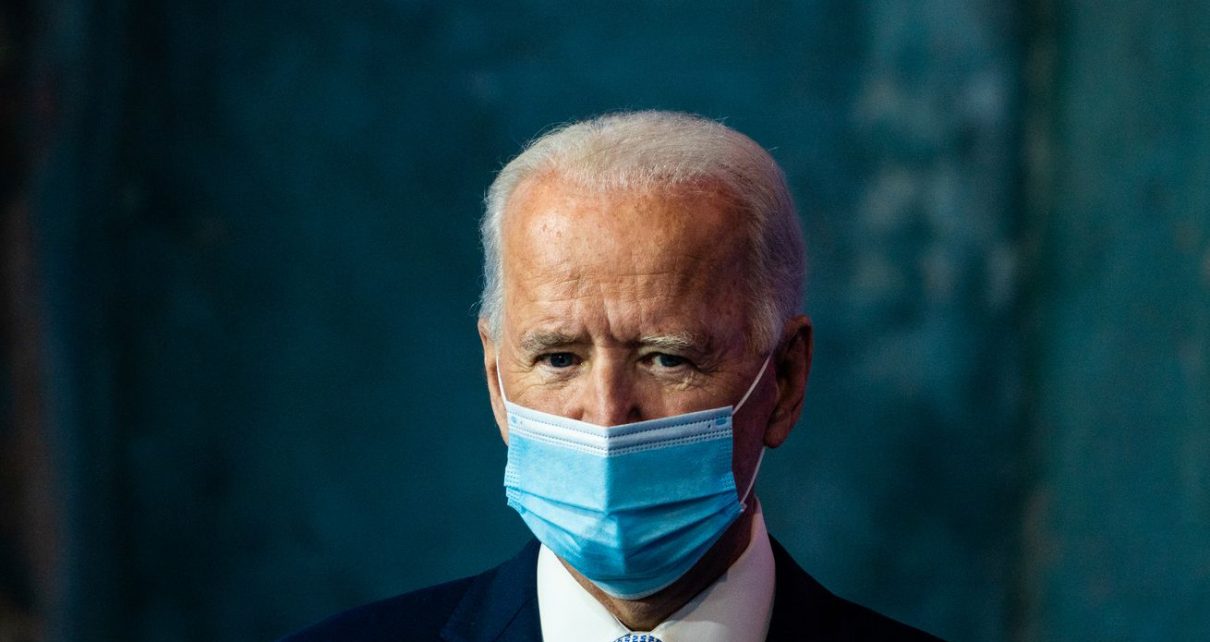

President Joe Biden’s international rebuild has begun.

Biden, in the first hours of his presidency, rejoined the Paris climate accord and is expected to recommit to the World Health Organization, fulfilling promises he made during the campaign.

He is also taking the first steps toward achieving his larger foreign policy agenda of restoring American leadership abroad.

But these day one orders are the easy part. Now Biden begins the difficult task of rebuilding trust among allies, and trying to prove America can be a reliable partner.

Over the past four years of the Trump administration’s “America First” foreign policy, other countries have taken leadership roles on climate change, and other powers, like China, have moved to fill the vacuum left behind by the United States in international institutions.

Biden also confronts public health, economic, and racial reckoning crises at home, along with the fallout from the startling attack on US democracy earlier this month.

The world watched the Capitol siege on January 6, and witnessed a US political system in disarray. It framed Washington as far from a stable partner. But with Biden’s announcements on the Paris deal and the WHO, the US is showing that it’s trying to start somewhere.

The US’s recommitment to Paris will give the deal its first real chance

Trump announced the US withdrawal from the Paris climate accord in June 2017, fulfilling a campaign promise of his own. The nonbinding treaty sets standards for emission reductions in an effort to keep the global temperature from warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius. A total of 189 countries are party to the agreement.

Based on the terms of the treaty, the US couldn’t officially step away from the deal until November 2020, though the Trump administration did indeed formally withdraw last year.

Biden is reversing that, and it’s a fairly easy reentry: The president writes a letter saying the US wants to get back in, and in 30 days, they will again become party to the treaty.

“That’s obviously, in and of itself, an important threshold, because it brings us back into the single collective international body dedicated to meeting the climate challenge,” Peter Ogden, vice president for energy, climate, and the environment at the United Nations Foundation, told me.

Ogden said the US will ultimately have to recalibrate its 2030 targets. That will involve domestic policy considerations, as it requires states, localities, and, most of all, businesses to achieve the benchmarks for curbing emissions.

Those targets are also incredibly important, Ogden said. “It will be both a practical guide for other countries who are looking to understand the kind of actions that the United States intends to move forward with,” he said. “But it’s also going to be an important guide for other countries, who are also looking at their own targets.”

Biden has said climate change will be a priority of his administration; he appointed John Kerry, former secretary of state, as the administration’s “climate czar.” The administration is reportedly considering convening a global climate summit. Rejoining Paris is, symbolically, the first act of Biden’s promise to make climate considerations a big part of his policy priorities.

More broadly, on climate change, the Biden administration can set the example of global leadership it wants, and collaborate with other partners, such as the European Union and the United Kingdom, who have continued to press forward with climate targets. The US, historically, has been the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, and a real commitment to from the US on climate change, as Ogden said, would serve as Paris accord’s first real test.

The Biden administration will recommit to the WHO — and global vaccine distribution

Alongside the global threat of climate change, the coronavirus pandemic is still raging. Containing the pandemic, and undertaking a global vaccination campaign, will require unprecedented resources and coordination.

Which is why Biden’s second step — a planned recommitment to the WHO — is also critically important, for fighting the pandemic and for other global health priorities.

The Trump administration blamed the WHO for its handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, and accused the agency of being a “puppet of China.” In July, the administration sent the World Health Organization notice of its intent to withdraw, which would have taken the US out of the body a year later, in 2021.

Biden just needs to rescind that withdrawal. But as Alynna Lyon, a United Nations expert and professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire, told me last year, the US’s reengagement with the WHO is not as simple as it sounds.

The Trump administration’s threat of withdrawal severely threatened the overall funding of the WHO, which forced other countries, like China, to pledge to make up for the shortfalls. The Trump administration also tried to gum up existing cooperation with the WHO, including trying to block contact between WHO officials and US officials this fall.

As Lyon said, the US is going to have to retool its relationship with the organization; it can’t just expect things to revert to back to the pre-Trump era. Other countries, specifically China, have filled the void left behind by the United States.

“They’ve had a seat at the table, they’re writing the checks, they are able to shape and frame and spin what the priorities are,” she told me in December. “The US is late to the game on this. It’s very difficult for the US to just kind of waltz back in and say, ‘We’re back.’”

The Biden administration is taking another step to show it wants to work with other countries on global health. On Tuesday, Antony Blinken, Biden’s pick for secretary of state, said during his confirmation hearing that the United States would join Covax, the WHO-linked initiative to deliver and equitably distribute the Covid-19 vaccine worldwide, specifically to lower-income countries. China joined the initiative at the last minute last year, and many of the US’s partners have made financial commitments to the program. Russia and the US were the two big holdouts, until now.

So getting back into these global bodies is a good first step. It does send a powerful message to America’s allies and adversaries alike. But it’s also impossible for the United States to just turn back the clock.

Biden has said “America is back.” But what is it coming back to?

Blinken also said at his confirmation hearing Tuesday that “humility and confidence” should be the flip sides of American leadership.

That humility should include a very obvious recognization that the world has changed in the past four years, and the multilateral institutions like the WHO have changed with them. Biden’s administration also needs to sell this vision at home, learning the lessons from the Trump years that it’s not a given that the US will be — or that the American public will want to see it be — the one setting the international agenda.

The recommitment to the Paris climate accord and the World Health Organization are, symbolically, the Biden team’s first olive branches to the rest of the world. “America is back” — if the world will have it.