A startup called Core Scientific announced this week that it has raised $23 million to expand its cryptocurrency mining operations. The company, based in Bellevue, Wash., is already running crypto mines in North Carolina, Georgia, and Kentucky, and plans to open more before long.

It’s not hard to understand why. Right now, a single Bitcoin—the digital mining equivalent of a gold nugget—is worth around $20,000. Mining a single Bitcoin block brings a reward of 6.25 of them, or about $125,000.

If Core Scientific’s mining ventures are successful, the company will not just make a lot of money. It will also help to repatriate crypto production to the United States, where Bitcoin got its start.

The recent resurgence in crypto mining feels like a good-news story. Mining companies like Core Scientific are in a position to make money and create jobs in rural areas, while also ensuring more Bitcoin—which is becoming a strategic asset—ends up in American hands.

But there are also reasons for caution. The last crypto-mining boom promised similar benefits but resulted in fly-by-night companies leaving a trail of scams and environmental degradation in their wake. Will the outcome be any different this time?

Digital picks and shovels

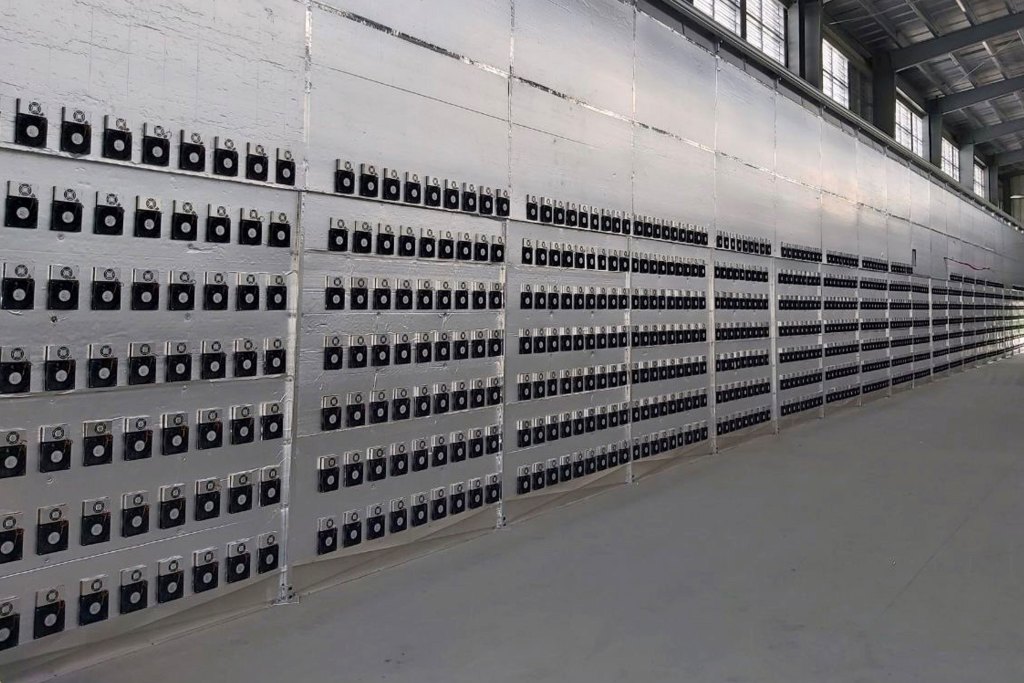

Mining cryptocurrency is different from conventional mining in some obvious ways. There’s no excavating and hauling ore. And the tools of the trade are not pickaxes and dynamite. Instead, crypto miners rely on two things to make a living: custom-designed computer chips and a torrent of electricity. A crypto-mining operation looks like this:

In order to find a digital nugget, crypto miners pit their computers against others around the world in a race to solve complex math problems. The computer that solves the problem broadcasts the solution to others on the network and, in doing so, adds a block to the blockchain—a tamperproof ledger that serves as a public record of transactions. For their trouble, the owner of the winning computer pockets the “block reward,” which is 6.25 Bitcoins in the case of Bitcoin plus transaction fees. The process is repeated every 10 minutes or so.

In the early days, when it was still viable to mine Bitcoin with a home laptop, a large proportion of crypto mining took place in the U.S. But as the computer power needed to solve the math problems increased, Chinese mining operations came to dominate.

The Chinese miners enjoyed two advantages: easy access to cheap power, including in places like Mongolia, and a domestic manufacturing base capable of cranking out so-called mining rigs—computers with custom chips made just for mining. While there are other mining operations around the globe, China remains far and away the leader, as can be seen in this chart from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance:

Now, some U.S. companies believe they can wrest some of the mining pie back from China. In the case of Core Scientific, it has struck arrangements for cheap power across five sites, spanning over 100 acres in total, in Dalton, Ga., Marble, N.C., and Calvert City, Ky. The firm has also cut deals with Chinese manufacturers to get first dibs on the newest mining rigs, and plans to mine not just Bitcoin but so-called alt coins like Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Zcash, and Ethereum.

Core Scientific is now one of the biggest U.S. miners, but its operations are part of a still larger plan. That plan is being steered by an outfit called Foundry, which is behind the just announced $23 million investment in Core Scientific. Foundry is a subsidiary of Digital Currency Group (DCG), a sprawling crypto conglomerate that recently announced it would spend $100 million on mining initiatives.

According to Foundry CEO Mike Colyer, boosting crypto production in the U.S. will serve to strengthen Bitcoin’s network by diversifying the miners who maintain it.

“The only way Bitcoin works is when it’s distributed through the world and when it’s decentralized,” says Colyer, who predicts the share of U.S.-produced Bitcoin could rise to 25% in the next few years.

Put another way, the U.S. mining ventures will help ensure that no consortium of miners can collude to manipulate the blockchain network. Such collusion requires a single entity to control over 50% of the network—a risk that is is remote in the case of Bitcoin, but which has transpired in the case of smaller digital currencies.

Foundry’s mining initiatives offer the promise of strengthening Bitcoin’s network—and, of course, giving the company a chance to make money—but may also reflect another strategic imperative. Namely, as demand for Bitcoin increases in the market, more companies may wish to have a private supply of it to facilitate trading operations. In the case of DCG, which has a giant consumer Bitcoin business, Foundry’s ventures may help facilitate vertical integration.

“Mining is a great way to accumulate Bitcoin. With the correct setup, you can mine it cheaper than you can buy it,” says Amanda Fabiano, who formerly oversaw mining operations at investment giant Fidelity and now does the same for crypto-trading firm Galaxy Digital.

The best use of power in a “carbon-challenged world”?

To get a different perspective on Bitcoin mining in North America, I spoke to Steve Wright, the general manager of a public utility in Chelan County, Wash. During the last big Bitcoin boom in 2017, Wright had to contend with a crush of mining companies asking to tap into the county’s ample hydroelectric resources.

“We had a lot of companies come in and say, ‘We’re going to do great things,’ and then they would be gone from the face of the earth,” Wright recalls. “People would say, ‘We’re here for long term,’ and then nobody would pick up the phone.”

Problems also came in the form of reckless operators who overloaded transformers, triggering fires. Meanwhile, the crypto miners who wanted to set up shop demanded the low electricity rates available to locals. For Wright, agreeing to those demands risked undercutting the profits the utility earned from selling its hydropower at higher rates to outside markets.

Wright also faced pushback from county residents who questioned whether it was ethical to expend energy on something like Bitcoin mining.

“When you have a green supply of power and you have a carbon-challenged world, people were asking if this is the best use of that power,” said Wright, whose job involves overseeing Columbia River dams like the one below.

The debate over the environmental impact of crypto mining is not restricted to Chelan County. The payment giant Square, which recently bought $50 million of Bitcoin for its corporate treasury, announced a $10 million pledge this week to support a “Bitcoin Clean Energy” initiative as part of a larger plan to become carbon neutral by 2030.

Meanwhile, other U.S. companies are finding creative ways to reduce Bitcoin’s environmental impact. Fabiano of Galaxy Digital pointed to three firms in the oil-and-gas field—Crusoe Energy, Great American Mining, and Upstream Data—that are capturing the energy typically wasted through flaring (when shale drilling rigs burn off excess natural gas) to power crypto mining.

All of this may help assuage critics who view Bitcoin mining as an environmental disaster. But firms like Core Scientific also have to overcome another public relations problem: that mining operations are run by shifty carpetbaggers who will leave local communities in the lurch.

This perception is another legacy of the 2017 Bitcoin boom when digital miners—who typically share the libertarian, borderless worldview of the larger crypto community—took towns across the country for a ride. The most famous example is Rockdale, Texas. The town became the subject of a Wired magazine feature about how a Chinese firm, Bitmain, touted a new Bitcoin venture that would help replace jobs and revenue that had been lost when an Alcoa plant closed. Rockdale town officials put on lavish dinners to make the mining executives feel welcome but, as happened in Chelan County and elsewhere, they vanished into the night.

As for jobs, cryptocurrency mining operations may provide a handful of new positions for local residents. But Wright says the employment opportunities are nothing like what a recently closed aluminum plant used to provide—meaning his county has less reason to roll out a welcome mat for crypto companies.

Colyer, the Foundry CEO, acknowledges the crypto-mining industry must overcome deep levels of mistrust. But he insists ventures like Core Scientific are a different breed from past fly-by-night operations.

“In 2017, there were lots of people making huge promises, running around the company, and scaring local governments. A lot of those people have disappeared, and the companies that are left are legitimate,” he says.

But even if the North American mining companies can overcome public skepticism, they will also have to prove they can succeed in a venture that has mostly been defined by failure.

Relying on Chinese chips

A successful crypto-mining operation requires the use of new machines built with ASIC chips—a type of computer chip custom-built for a specific purpose. In the case of Bitcoin mining rigs, the chips are specially designed to crunch the math problems that build the blockchain.

This raises an obvious question: If a company can manufacture the best mining rigs, why would it sell them rather than set up a Bitcoin-mining operation of its own?

And indeed Bitmain, one of the two Chinese companies that makes most of the machines, has faced past accusations of passing off used mining rigs as new. Meanwhile, the company is the subject of an ongoing class action lawsuit that claims it surreptitiously mined Bitcoins purchased by its customers.

The allegations are unproven, and Bitmain denies wrongdoing. But the situation appears to pose a risk for the likes of Foundry and Core Scientific, which are not only undertaking their own mining operations but plan to supply machines to other companies.

Colyer of Foundry says that such concerns were valid in the past but that the mining industry has evolved to eliminate self-dealing by the Chinese manufacturers. One reason, he says, is that the manufacturers have come to recognize that distributing mining power across the globe benefits the broader Bitcoin economy.

Fabiano, the mining expert with Galaxy Digital, says the industry has become more trustworthy in part because there is now intense competition between Bitmain and the other big manufacturer, MicroBT.

But Fabiano adds that accessing state-of-the-art mining rigs, which can cost between $2,600 and $2,800 apiece, has become difficult as a result of supply chain issues. She notes that the companies obtain their chips from Taiwan-based TSMC and Samsung, and that those companies have hundreds of other clients—including the likes of Apple—that may receive priority over Bitcoin companies. The upshot, says Fabiano, is that new machines may not be available until next July.

In the long term, Core Scientific executives predict that chipmakers like TSMC may set up production in the U.S. and provide a domestic source of mining equipment. But Fabiano suggests that China will always have the manufacturing edge and that Colyer’s prediction of the U.S. obtaining a 25% share of mining capacity is optimistic.

The bottom line is that aspirations for a booming crypto-mining industry in the U.S. is risky and fraught with uncertainty—much like Bitcoin itself.

More must-read finance coverage from Fortune:

- Why aren’t we in another Great Depression?

- The IRS effectively canceled the tax break that made PPP loans so valuable

- A $100 million “virtual power plant” could put an end to California’s power woes

- Robinhood’s next adventure: Stealing market share from the rich

- Commentary: The 20 most important personal finance laws to live by