“Whatever has happened, whatever is going to happen in the world, it is the living moment that contains the sum of the excitement, this moment in which we touch life and all the energy of the past and future.”

It is such delicate work, such devoted work, the work of contouring the personhoods of persons who have imprinted the world with nothing less than revolutions of the mind, yet have left only faint traces of themselves as persons, unselved first by the nature of their revolutionary ideas — vast, abstract, lightyears beyond the solipsisms of the self — and then unselved again by the selective collective memory we mistake for history and its perennial failure at a foothold in the abstract beyond personhoods, beyond identities, beyond the narrow and unimaginative bounds of so-called human interest. There is quiet heroism to this work of rescuing from obscurity and erasure lives understanding which helps understand the entire eras in which they were lived and the fundaments of sensemaking the following epochs have taken as givens.

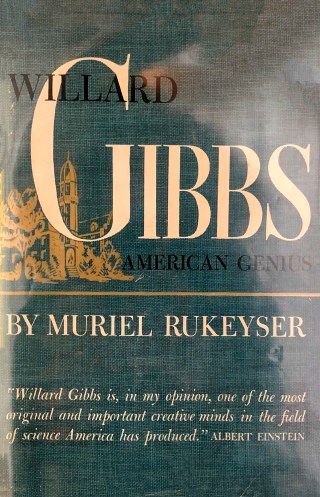

Such is the work Muriel Rukeyser (December 15, 1913–February 12, 1980) did with Willard Gibbs: American Genius (public library).

Rukeyser’s own genius came abloom in the dawn of her twenties, when her debut poetry collection, Theory of Flight, earned her the Yale Younger Poets Award — America’s longest-running literary accolade. She was not yet thirty when she composed her staggering more-than-biography of the father of physical chemistry, Willard Gibbs (February 11, 1839–April 28, 1903) — this odd and world-shifting bridge figure between classical mechanics and quantum physics, celebrated as the greatest mind of the nineteenth century, lauded by Einstein as one of the most original and important thinkers America ever produced, prophesied to outlive in remembrance all of his contemporaries except perhaps Lincoln, yet almost entirely forgotten by Rukeyser’s time.

Like Eddington, Gibbs was a quiet, reserved genius — “silent, inhibited, remote,” Rukeyser tells us — queer by all reasonable deduction; he never married and lived out his life in his sister’s home. Like Newton, who accomplished the greatest leap in science within the solitude of his plague quarantine, Gibbs imagined his revolution within the chamber of the mind, within a dense solitude — “in silence, in isolation, in the years of rejection directly after the Civil War, when abstract work was wanted least of all, when the cry was for application and invention and the tools that would expand the great growing fortunes of the diamond boys.” And yet there he was, living “closer than any inventor, any poet, any scientific worker in pure imagination to the life of the inventive and organizing spirit of America.”

Rukeyser’s enchantment with Gibbs became the crucible for her lifelong stewardship of the parallels between poetry and science, her astute and abiding insight into how they help hold “the giant clusters of event and meaning that every day appear” and in doing so “equip our imaginations to deal with our lives.”

Published in 1942, Rukeyser’s majestic 446-page masterwork of antierasure grew from the seed of a fascination first germinated with her poem “Gibbs,” written as WWII was beginning to cast its umbra of terror over all that is bright and beautiful in the human spirit, unpeeling from the hallways of time the image of every genius who ever lived as an irrelevance to this apotheosis of dumb destruction. It is always the poet’s task to defend the relevance of radiance, whatever its shape and subject, and so she did. From the life of Willard Gibbs, Muriel Rukeyser drew something larger, vaster, more radiant than his life, than any life — a celebration of life itself, of the living mind and its deathless imagination and the power of that imagination to irradiate the world with the wonder of possibility. It is the connective tissue of her thought, the poetic musculature of context and concept propping up the skeleton of the dead scientist’s life, that renders Rukeyser’s book a revelation from the opening page:

Whatever has happened, whatever is going to happen in the world, it is the living moment that contains the sum of the excitement, this moment in which we touch life and all the energy of the past and future. Here is all the developing greatness of the dream of the world, the pure flash of momentary imagination, the vision of life lived outside of triumph or defeat, in continual triumph and defeat, in the present, alive. All the crafts of subtlety, all the effort, all the loneliness and death, the thin and blazing threads of reason, the spill of blessing, the passion behind these silences — all the invention turns to one end: the fertilizing of the moment, so that there may be more life.

Writing from within the savage wastefulness of a particular moment in a world unworlded by its most destructive war yet, Rukeyser insists on the irrepressible aliveness that consecrates the present, any present, and that springs from the indivisibility of the life of the body and the life of the mind:

Spring, and the years, the wars, and the ideas rejected, the swarming and anonymous people rejected, and the slow climb of thought to be more whole, the few accepted flames of truth in a darkness of battle and further rejection and further battle. We know the darkness of the past, we have a conscious body of knowledge — and under it, the black country of a lost and wasted and anonymous world… jungle-land, wasteful as nature, prodigal.

Our living moment rides this confusion; it is torn by the dead wars; seizes the old knowledge; speeds on the imagination of the living and the dead, and passes, fertilized. But the hidden life today continues among all the silence, and in the midst of war. The hidden life of the senses, the vivid, speculative life of the mind. The man over his table, glass shine of the test-tubes reflected in the eyes; the woman staring into her thought of the child not yet born… We see, in this moment of the world, the lives of many people brought to a time of stress. The streams are challenged, all the meanings are again in question.

In a sentiment which Octavio Paz (whom Rukeyser translated) would come to echo several years later in his observation that “there is something revealing in the insistence with which a people will question itself during certain periods of its growth,” she adds:

It is at this moment that we turn… In the imaginations which tapped that energy, in the energy itself and its release, we see our power. Man*, the mystery; man, the pure force; man, the taproot of naked vision, the source himself, will look in such a moment for deeper sources, for the sources of power that can bring a fuller life to a desperate time. We cut away the old life, cutting down to the root. And the root of such power, of such invention, is in the imaginative lives of certain men and women, responding in their way and with their proper kinds of love to the wishes of history — that is, to the wishes of the people at that moment, however disguised, however premature and dark.

For Rukeyser, Willard Gibbs was one of those people; for me, the people whose lives and loves I contoured in Figuring were, and the people in whose lives and loves I have dwelt in the years since: Mary Shelley, Walt Whitman, Rukeyser herself.

Rukeyser notes that however rigorous our scholarship, it is always at bottom a presumption to attempt to “solve the personality” and reanimate the lives and worlds of the long-gone people whose work has shaped our own lives and our understanding of the world. In a passage to which I relate in the marrow of my being, she adds:

It is by a long road of presumption that I come to Willard Gibbs. When one is a woman, when one is writing poems, when one is drawn through a passion to know people today and the web in which they, suffering, find themselves, to learn the people, to dissect the web, one deals with the processes themselves. To know the processes and the machines of process: plane and dynamo, gun and dam. To see and declare the full disaster that the people have brought on themselves by letting these processes slip out of control of the people. To look for the sources of energy, sources that will enable us to find the strength for the leaps that must be made. To find sources, in our own people, in the living people. And to be able to trace the gifts made to us to two roots: the infinite anonymous bodies of the dead, and the unique few who, out of great wealth of spirit, were able to make their own gifts.

In consonance with my longtime conviction that history is not what happened, but what survives the shipwrecks of judgment and chance, Rukeyser mourns the erasure of so many such titans of spirit from our collective selective memory, mourns their loss “through waste and carelessness,” and offers the single most poignant and precise diagnosis I have ever encountered of what ails our systems of remembrance and sensemaking, which are ultimately our systems of future-making:

This carelessness is complicated and specialized. It is a main symptom of the disease of our schools, which let the kinds of knowledge fall away from each other, and waste knowledge, and time, and people. All our training plays into this; our arts do; and our government. It is a disease of organization, it makes more waste and war.

Both in her choice of subject (a man of such singular, specialized, abstract genius) and in her treatment of it (so rigorous in scholarship, so rapturous in breadth of sentiment), Rukeyser’s Willard Gibbs stands as a bold antidote to this cultural carelessness — and falls as one, having perished out of print by these very forces, these abiding emblems of the ahistorical and segregationist impulses arising in the puerile bosom of our species, which might, just might, one day mature to outgrow. Until then, we have the poets — in the largest Baldwinian sense — to salve our collective amnesia with their bold benedictions of immortal truth.

donating = loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes me hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most unmissable reads. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.