“Innovators always seek to revitalize, extend and reconstruct the status quo in their given fields… Quite often they are the rejects, outcasts, sub-citizens, etc. of the very societies to which they bring so much sustenance.”

To create anything of beauty, daring, and substance that makes the world see itself afresh — be it a revolutionary law of planetary motion or the Starry Night — is the work of lonely persistence against the tides of convention and conformity, often at the cost of the visionary’s aching ostracism from the status quo they are challenging with their vision. Rilke recognized this when he observed that “works of art are of an infinite loneliness” and Baldwin recognized it in his classic investigation of the creative process, in which he argued that the primary distinction of the artist is the willingness to maintain the state everyone else most zealously avoids: aloneness — not the romantic solitude of the hermit by the silver stream, but the raw existential and creative loneliness Baldwin likened to “the aloneness of birth or death” or “the aloneness of love, the force and mystery that so many have extolled and so many have cursed, but which no one has ever understood or ever really been able to control.”

This love-like force — the creative force — is what fuels the perseverance necessary to usher in a new way of seeing or a new way of being. It is the life-force by which visionaries survive the aloneness of their countercultural lives.

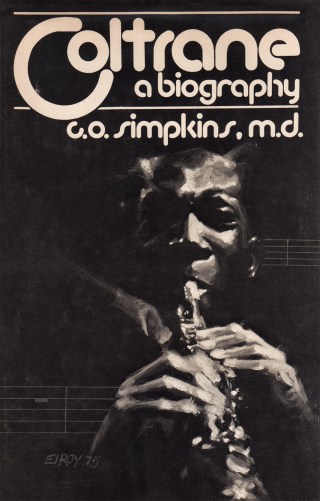

That is what jazz legend John Coltrane (September 23, 1926–July 17, 1967) addressed in an extraordinary letter penned in the late spring of 1962, posthumously included in Cuthbert Ormond Simpkins’s excellent 1975 biography Coltrane (public library).

John Coltrane (Courtesy of johncoltrane.com.)

One June morning two years after the release of his epoch-making Giant Steps and five years before his untimely death of cancer, Coltrane opened his mailbox to discover a package from the editor of Downbeat magazine, the premier journal of jazz, containing a gift: a copy of Music and Imagination — a book of the six lectures the great composer and creativity-contemplator Aaron Copland had delivered at Harvard a decade earlier.

Coltrane’s letter of thanks for the gift unspools into one of those rare miracles when something small and seemingly peripheral prompts a sweeping yet succinct formulation of a visionary’s personal philosophy and creative credo — Coltrane’s most direct meditation on what it means to be an artist.

Millennia after Pythagoras’s revolutionary yet limited mathematics of music forked the sonic path of the modern world by laying the structural foundation of the Western canon but failing to account for the intricate unstructured musical styles of the African diaspora and my own native Balkans — a cultural irony, given Pythagoras developed his theory on the island of Samos, a thriving cross-pollinator of the Ancient Greek world perched midway between Africa and the Balkans — Coltrane observes that Copland’s lectures, while erudite and philosophically insightful, speak more to musicians in the Western tradition than they do to jazz musicians. Against Copland’s concern about how difficult it can be for artists to find “a positive philosophy or justification” for their art, Coltrane holds up jazz as living counterpoint — a musical tradition that began as an affirmation of life amid unimaginable hardship, provided a lifeline for those who conceived it and partook of it, and has thrived on the wings of this inherent buoyancy.

Art from The First Book of Jazz by Langston Hughes, 1954

He writes:

It is really easy for us [jazz musicians] to create. We are born with this feeling that just comes out no matter what conditions exist. Otherwise, how could our founding fathers have produced this music in the first place when they surely found themselves (as many of us do today) existing in hostile communities when there was everything to fear and damn few to trust. Any music which could grow and propagate itself as our music has, must have a hell of an affirmative belief inherent in it.

Since we read (and write) about other lives to make sense of our own, he reflects on a biography has been reading of Van Gogh — an artist who spent his short, revolutionary, tragic life negotiating between his private suffering and the irrepressible affirmative belief that forever changed art. With an eye to Van Gogh, Coltrane writes:

Truth is indestructible… History shows (and it’s the same way today) that the innovator is more often than not met with some degree of condemnation; usually according to the degree of his departure from the prevailing modes of expression or what have you. Change is always so hard to accept.

Vincent van Gogh: The Mulberry Tree, 1889.

In a sentiment evocative of artist Egon Schiele’s observation that visionaries tend to come from the minority and echoing the seventh of Bertrand Russell’s ten commandments of critical thinking — “Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.” — Coltrane adds:

Innovators always seek to revitalize, extend and reconstruct the status quo in their given fields, wherever it is needed. Quite often they are the rejects, outcasts, sub-citizens, etc. of the very societies to which they bring so much sustenance. Often they are people who endure great personal tragedy in their lives. Whatever the case, whether accepted or rejected, rich or poor, they are forever guided by that great and eternal constant — the creative urge.

This might be the most succinct summation of my creative choice of historical figures to celebrate in Figuring. It is also what Virginia Woolf meant when she wrote of the “shock-receiving capacity” necessary for being an artist, and what Patti Smith meant when, with an eye to Coltrane, she considered the shamanistic channeling at the heart of the creative impulse.

Complement with Coltrane’s contemporary and fellow jazz legend Bill Evans on the creative process, then revisit Walt Whitman on how to keep criticism from sinking your creative confidence.

donating = loving

For 15 years, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month to keep Brain Pickings going. It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your life more livable in any way, please consider aiding its sustenance with donation.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.