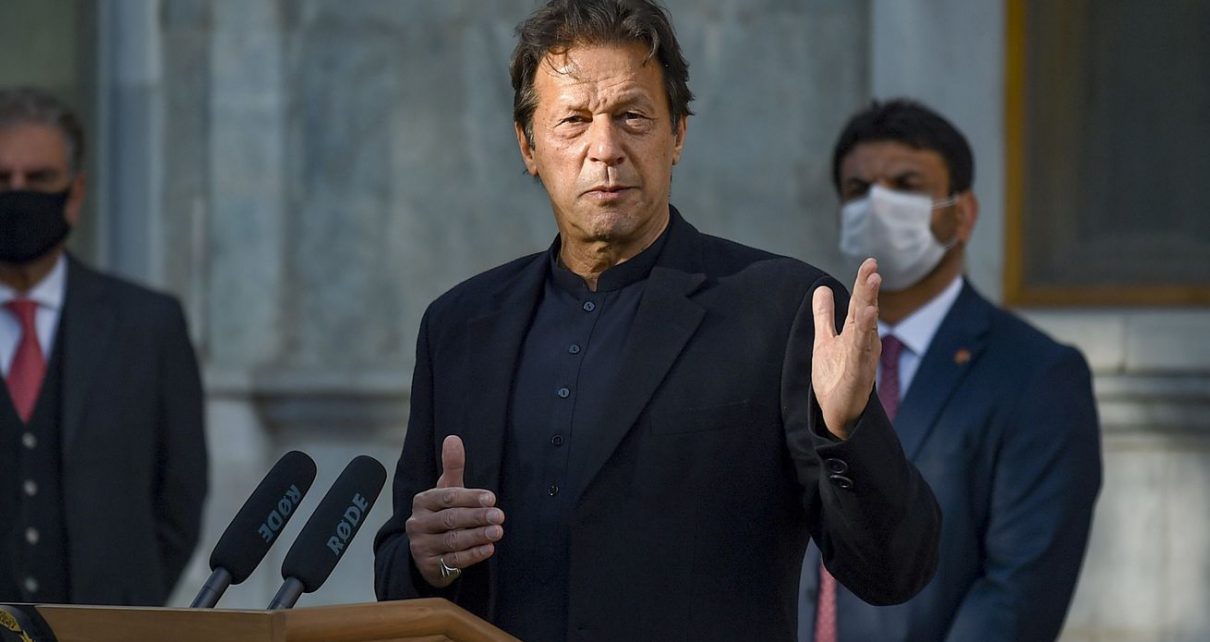

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Axios interview is another example of this worrying trend.

As the world increasingly speaks out against China’s genocide of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, the quietest voices continue to belong to the leaders of Muslim-majority countries.

Look no further than Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s interview this week with Axios’s Jonathan Swan. Swan asked why the premier, who often speaks out on Islamophobia in the West, has been noticeably silent on the human rights atrocities happening just across his country’s border.

Khan parroted China’s denial that it has placed roughly 2 million Uyghurs in internment camps and then evaded the issue over and over again. “This is not the case, according to them,” Khan said, adding that any disagreements between Pakistan and China are hashed out privately.

That’s a jarring statement. Instead of offering a pro forma “Yes, of course we’re concerned by this” before moving on, Khan chose instead to minimize the problem altogether.

Why would Khan do such a thing during a high-profile interview, with his self-enhanced image as a defender of Muslims on the line? The prime minister gave the game away later in the interview: “China has been one of the greatest friends to us in our most difficult times, when we were really struggling,” Khan told Swan. “When our economy was struggling, China came to our rescue.”

China has given Pakistan billions in loans to prop up its economy, allowing the country to improve transit systems and a failing electrical grid, among other things. China didn’t do that out of the goodness of its heart; it did so partly to make Pakistan dependent on China, thus strong-arming it into a closer bilateral relationship.

It’s a play China has run over and over through its “Belt and Road Initiative.” China aims to build a large land-and-sea trading network connecting much of Asia to Europe, Africa, and beyond. To do that, it makes investment and loan deals with nations on that “road” — like Pakistan — so that they form part of the network. The trade, in effect, is that China increases its power and influence while other countries get the economic assistance they need.

That relationship has helped Pakistan avoid economic calamity. But as of right now, it doesn’t have the funds to pay China back. That could spell trouble for Pakistan, as China has a history of taking a nation’s assets when it doesn’t pay its debts, like when it took over a Sri Lankan port in 2018.

To avoid a similar fate, and perhaps keep the money flowing, Khan likely didn’t want to badmouth China in public. “China is Pakistan’s only lifeline out of debt,” said Sameer Lalwani, director of the South Asia program at the Stimson Center in Washington, DC.

Look elsewhere in the world and the story is essentially the same. Even the leaders of Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey — who often portray themselves as the defenders of Islam and of the ummah, the global Muslim community — are choosing to prioritize their economic relationship with China over standing up for the Uyghurs.

In the short term, they may get more funds from the relationship with China, but in the long run, the price they pay is in their reputation.

China is buying Muslim leaders’ silence on the Uyghurs

George Mason University’s Jonathan Hoffman, who studies Middle Eastern politics and geopolitical competition, told me Khan’s statements are in line with the trend of Muslim leaders turning away from China’s gross human rights abuses.

They “represent a broader pattern in the region where the plight of the Uyghurs is sidelined as China has quickly become the largest oil consumer, trade partner, and investor,” he told me.

That helps explain some of the actions by Muslim-majority nations and their leaders in recent years, which Hoffman wrote about in May for the Washington Post:

In 2019, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt were among 37 countries that signed a letter to the U.N. Human Rights Council praising China’s “contribution to the international human rights cause” — with claims that China restored “safety and security” after facing “terrorism, separatism and extremism” in Xinjiang…

When Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman visited China in 2019, he declared that “China has the right to take anti‐terrorism and de‐extremism measures to safeguard national security.” And a March 2019 statement by the Saudi‐based Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) praised China for “providing care to its Muslim citizens.”

The most egregious example of how China has bought loyalty, compliance, and silence, though, may be Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22675360/GettyImages_1154857596_copy.jpg) Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

Greg Baker/AFP/Getty ImagesIn 2009 — as Chinese authorities cracked down on Uyghurs amid ethnic violence in Xinjiang, and long before there were credible reports of arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and forced labor — the Turkish leader spoke out about what was happening.

“The incidents in China are, simply put, a genocide. There’s no point in interpreting this otherwise,” Erdoğan said.

But now his tune has changed. In January, Turkish police broke up a protest led by local Uyghurs outside China’s consulate in Istanbul, and the government stands accused of extraditing Uyghurs to China in exchange for Covid-19 vaccines.

Why such a shift? You guessed it: Money.

The Turkish economy was in a downturn well before the coronavirus pandemic, but China has come to the rescue. Erdoğan and his team have sought billions from China in recent years, and China became the largest importer of Turkish goods in 2020. Saying anything negative about the Chinese government — especially on the Uyghur issue — could sever the financial lifeline China provides.

That said, the pressure from the pro-Uyghur public in Turkey has forced a slight shift in the Erdoğan regime’s rhetoric in recent months. In March, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said his administration has brought up the plight of the Uyghurs in private discussions with Chinese officials.

Still, that falls far short of what the world should expect from Muslim leaders.