-

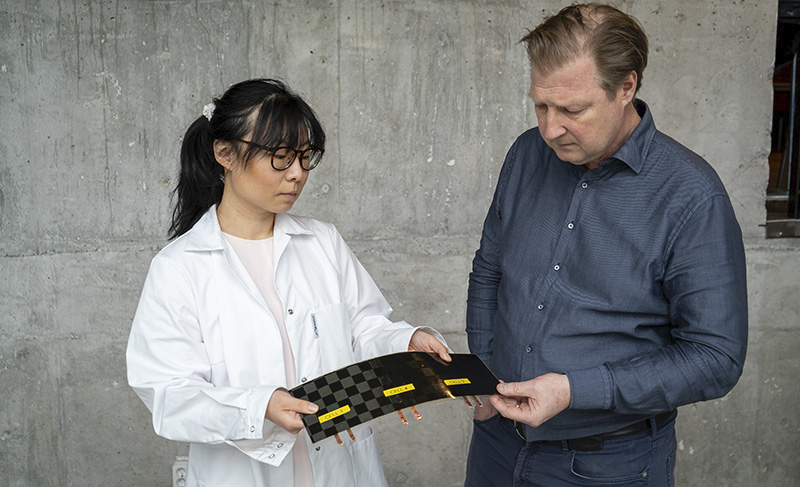

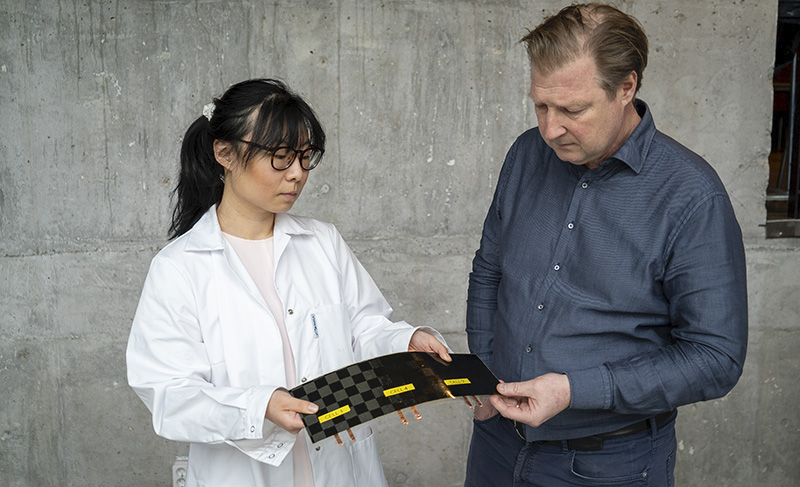

Doctor Johanna Xu with a newly manufactured structural battery cell in Chalmers’ composite lab, which she shows to professor Leif Asp. [credit: Marcus Folino ]

Over the next few years, the batteries that go into electric vehicles are going to get cheap enough that an EV should cost no more than an equivalent-sized vehicle with an internal combustion engine. But those EVs are still going to weigh more than their gas-powered counterparts—particularly if the market insists on longer and longer range estimates—with the battery pack contributing 20-25 percent of the total mass of the vehicle.

But there is a solution: turn some of the car’s structural components into batteries themselves. Do that, and your battery weight effectively vanishes because regardless of powertrain, every vehicle still needs structural components to hold it together. It’s an approach that groups around the world have been pursuing for some time now, and the idea was neatly explained by Volvo’s chief technology officer Henrik Green when Ars spoke with him in early March:

What we have learned… just to take an example: “How do you integrate the most efficiently a battery cell into a car?” Well, if you do it in a traditional way, you put the cell into the box, call it the module; you put a number of modules into a box, you call that the pack. You put the pack into a vehicle and then you have a standardized solution and you can scale it for 10 years and 10 manufacturing slots.

But in essence, that’s a quite inefficient solution in terms of weight and space, etc. So here you could really go deeper, and how would you directly integrate the cells into a body and get rid of these modules and packs and stuff in between? That is the challenge that we are working with in future generations, and that will change how you fundamentally build cars. You might have thought that time of changing that would have ended, but it has just been reborn.

Tesla is known to be working on designing new battery modules that also work as structural elements, but the California automaker is fashioning those structural modules out of traditional cylindrical cells. There’s a more elegant approach to the idea, though, and a group at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden led by Professor Leif Asp has just made a bit of a breakthrough in that regard, making each component of the battery out of materials that work structurally as well as electrically.