Because grief, too, is a thing with feathers.

“Grief is a force of energy that cannot be controlled or predicted,” Elizabeth Gilbert wrote in her loss-lensed reflection on life. “In that regard, Grief has a lot in common with Love.” Indeed, it is often said that grief is the price we pay for love, that grief is love’s other side. But I have found that grief is also the other side of hope, and hope is what lives on the other side of grief. Grief, too, is a thing with feathers. These are the twin wings of what may be the most quietly powerful of human passions: longing — grief, the longing for something that once was, is no more, and never again could be; hope, the longing for something that could be but is not, not yet.

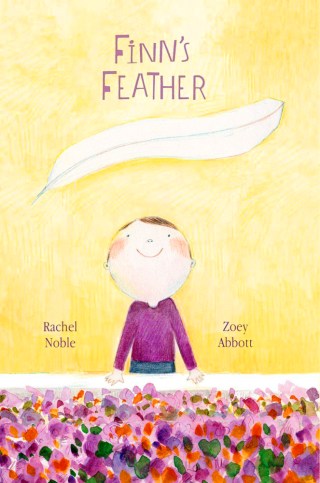

These are the thoughts I am having while leafing through an uncommonly tender book full of feeling: Finn’s Feather (public library) by Australian author Rachel Noble, illustrated by Portland-based artist Zooey Abbott — a fine addition to the most soulful and sensitive books to help young humans grieve and make sense of loss.

Fomented by the feather Noble herself found on her own doorstep after the death of her own son, Hamish, the magical-realist story follows a boy named Finn, who finds a large white feather, beautiful and perfect, on his doorstep on the first day of spring after the long winter that is grief: grief for is brother, Hamish.

Immediately, Finn decides that the feather is a gift from Hamish.

“Bubbling with excitement,” he runs to his mother with the feather to tell her. But she meets it with “a deep breath” and “a great, big hug.”

Puzzled that she is not more excited about the feather — “it was definitely from Hamish” — Finn takes it to school to show it to his teacher.

But she too meets it with “a deep breath” and “a great, big smile.”

Just as Finn’s confusion about the grownups’ reaction begins collapsing into sadness, his friend Lucas appears at lunch and asks about the beautiful white feather.

“I think my brother Hamish sent it.”

“Really?” Angels can do that?” asked Lucas.

“I think they can,” said Finn.

“It’s a nice feather.”

“It’s amazing!”

I am reminded of William Blake’s first vision as a child — a tree filled with angels that had appeared to him while walking through one of London’s parks. And how, upon returning home and recounting the vision to his parents, he incurred a wrathful punishment for what his father took to be a lie. And how children believe the world as it appears to them unquestioningly, until made to feel wrong in their beliefs. And how all belief is simply how we process our feelings about reality, and how therefore there are no right or wrong beliefs — only true beliefs.

Pondering why Hamish might have sent the feather, Finn and Lucas decide that it must be to encourage Finn to have more fun. (This, after all, is the heaviest hope we carry while hollowed by grief — that life will one day be enjoyable and full again.)

They decide to build “the biggest castle in the whole world and tick the feather on top!” And so they do.

Finn and Lucas relish watching the other kids admire their miniature cathedral, complete with the shimmering spire of the white feather, then go on adventuring — the feather as plaything, the feather as emblem of delight, the feather as instrument of aliveness.

“This feather is the best!” said Lucas. “It’s so great that Hamish left it for you. He’s a really cool angel.”

“He was a really cool brother. I miss him.”

Finn ran his finger down the spine of the feather, happy to have his friend at his side.

But then, just like that, the wind snatches the feather from Finn’s hands and whisks it away.

The boys chase after it in despair, until a tree catches it in a crown too high for Finn to reach. And so the other children flock to lift him up.

So too with life: Eventually, it snatches away everything and everyone we love, including our own lease on it. Along the way, we have only love and the lever of sympathy to lift us up.

When Finn returns from school and tells his mother about his fun day with the feather, she still meets it with a deep breath, but this time she smiles as she gives him that “great, big hug.”

Somehow, Finn’s belief in the feather — now no longer white and perfect — seems to have revivified some of her own belief in life, painfully imperfect and love-worn as it may be.

Complement with the German gem of a picture-book Duck, Death, and the Tulip, the French gem of a picture-book The Scar, the Danish gem of a picture-book Cry, Heart, But Never Break — also from my friends at Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion, who published Finn’s Feather (and my own children’s book on a not entirely unrelated theme) — then, for a grownup counterpart, savor Kathryn Schulz on losing love, finding love, and living with the fragility of it all, Nick Cave on grief as a portal to aliveness, and Emily Dickinson on love and loss.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.