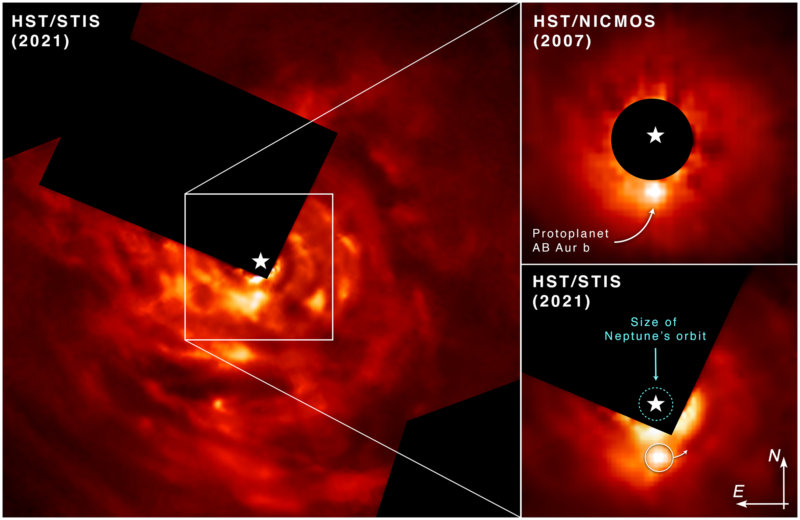

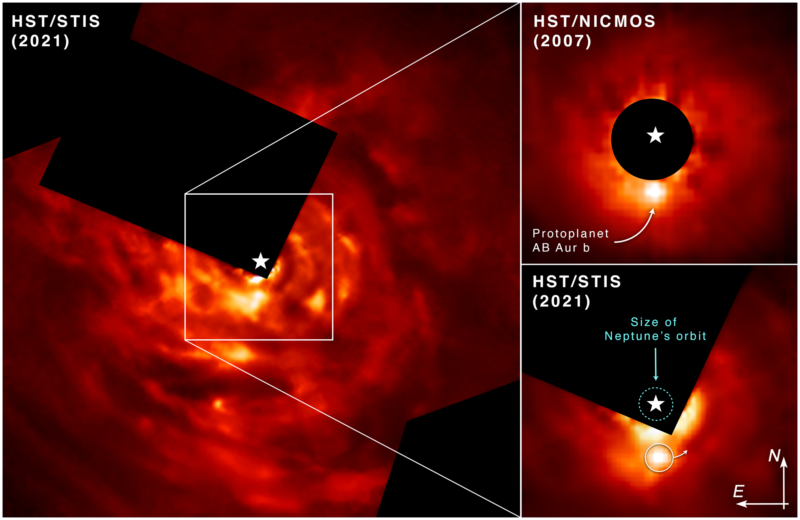

Enlarge / Image of the AB Aurigae system, with details of the object shown at the right. (credit: NASA, ESA, Thayne Currie)

On some levels, forming stars and planets is simple: They form where there’s more stuff. So, while the raw material for a star may be a diffuse cloud of gas, the distribution of that gas isn’t entirely even. Over time, the gravitational pull of areas that had somewhat more material will pull ever more material in, eventually resulting in enough matter to form a star. Or two—in many cases, more than one concentration of matter will form; in other cases, a single concentration will split into two. Planets also form where the matter is, being generated by the disk of material that feeds the forming star.

While this might generally be true, there are a couple of problems with it. For one, there’s no clear dividing line between small stars like brown dwarfs and enormous planets we’ve put in a category called super-Jupiters. And the handful of planets we’ve been able to image directly appear to be orbiting far from their host star, where there should not be much matter around to drive their formation.

This week, astronomers announced the imaging of a super-Jupiter in the process of forming, far from the star it appears to be orbiting. This suggests the planet is likely forming via a process that typically produces stars and not through the one that produces gas giants like Jupiter.