“To love anybody is to expect something from him, something which can neither be defined nor foreseen; it is at the same time in someway to make it possible for him to fulfill this expectation.”

The capacity for hope is not merely a hallmark of human consciousness — it is the supreme umbilical cord between consciousnesses. To place our hope in another person is to instantly entwine destinies, linking self and other in a tender and tenacious recognition of interdependence. All love is a form of hope. All hope is the work of absolute sincerity, which is the emblem of being fully human.

A cynic would hasten to retort that this openhearted expectancy is precisely what makes hope a portal to disappointment — but cynicism is, of course, the terror of sincerity, the cowardly attempt at self-protection from the heartache of unmet hope. If we are serious about the evolution of consciousness — and of our understanding of consciousness — we must place hope at the helm.

Light distribution on soap bubble from a 19th-century French science textbook. (Available as a print.)

It has taken us four centuries to revise the dangerous Cartesian reductionism of “I think, therefore I am” into a version of “I feel, therefore I am” as neuroscience is reaching beyond the brain to illuminate our conscious experience as a full-body phenomenon. The next frontier might be “I hope, therefore we are” — hope is the poetics of conscious interbeing, transforming the other from object to subject, the way poetry subjectifies the universe.

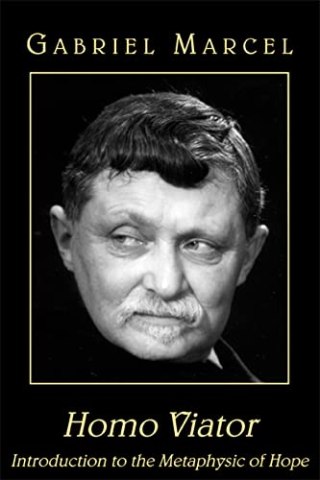

The French philosopher and playwright Gabriel Marcel (December 7, 1889–October 8, 1973) explores this with uncommon intellectual elegance and sensitivity in his 1962 book Homo Viator: Introduction to the Metaphysic of Hope (public library). Challenging the ordinary understanding of otherness as absolute — as a clear demarcation between person and person — Marcel reframes it as a relative position, oriented by hope:

My relationship to myself is mediated by the presence of the other person, by what he is for me and what I am for him. To love anybody is to expect something from him, something which can neither be defined nor foreseen; it is at the same time in someway to make it possible for him to fulfill this expectation. Yes, paradoxical as it may seem, to expect is in someway to give: but the opposite is none the less true; no longer to expect is to strike with the sterility the being from whom no more is expected. It is then in some way to deprive him or to take from him in advance what is surely a certain possibility of inventing or creating [himself]. Everything looks as though we can only speak of hope where the interaction exists between him who gives and him who receives, where there is that exchange which is the mark of all spiritual life.

to love is to expect by Corita Kent, based on Marcel’s writings. Serigraph screen print. Corita Art Center.

This dialogue between giving and receiving, Marcel intimates, is the natural gateway to self-transcendence as giver and receiver enter a kind of disinterested and nonjudgmental love — love beyond demand and neediness, which are problems of self-concern and self-reference, problems not of expectation but of the judgment of expectation. He writes:

It is precisely where such love exists, and only where it exists, that we can speak of hope.

[…]

We might say that hope is essentially the availability of a soul which has entered intimately enough into the experience of communion to accomplish in the teeth of will and knowledge the transcendent act.

Art by Dorothy Lathrop, 1922. (Available as a print.)

Viewed as self-transcendence, hope becomes a compassionate exchange not only between two people but between all people — an exercise in “widening our circles of compassion,” to borrow Einstein’s lovely phrase. Marcel honed this insight on the whetstone of wartime terror during the Nazi occupation of France, addressing the question of how one can go on hoping amid a world that so readily compels to despair, and whether to hope or not to hope is even a personal choice at all in such a world. (Meanwhile, his compatriot Albert Camus was polishing his impassioned conviction that “there is no love of life without despair of life.”) To those who feel imprisoned by despair, for whom to hope appears utterly beyond their power, Marcel answers with the ultimate, most lucid and luminous antidote to cynicism, which is at bottom a form of alienation from life and each other:

The simple fact that you ask me the question already constitutes a sort of first breach in your prison. In reality it is not simply a question you ask me; it is an appeal you address to me, and to which I can only respond by urging you not only to depend on me but also not to give up, not to let go, and, if only very humbly and feebly, to act as if this Hope lived in you… What is important to understand thoroughly is that if it is shifted to the level of intersubjectivity, the problem changes its nature: the despairing person ceases to be an object about which one asks [and] is re-established in his condition as a subject, and at the same time, he is integrated into a living relation with the world of men, from which he had cut himself off.

Art by Dorothy Lathrop, 1922. (Available as a print and as stationery cards.)

The year Gabriel Marcel died, as entire nations were cutting themselves off from each other in the Cold War’s atmosphere of mutual terror, E.B. White considered the question of hope amid pervasive despair in his lovely letter to a man who had lost faith in humanity. Half a century later, Nick Cave took up the subject in answering a young father’s question about how not to taint his small son with his own loss of hope and faith in humanity, his growing cynicism, his despair. Cave writes:

Cynicism is not a neutral position — and although it asks almost nothing of us, it is highly infectious and unbelievably destructive. In my view, it is the most common and easy of evils.

I know this because much of my early life was spent holding the world and the people in it in contempt. It was a position both seductive and indulgent. The truth is, I was young and had no idea what was coming down the line. I lacked the knowledge, the foresight, the self-awareness. I just didn’t know.

With an eye to his own life-recalibrating collision with loss, Cave adds:

It took a devastation to teach me the preciousness of life and the essential goodness of people. It took a devastation to reveal the precariousness of the world, of its very soul, to understand that it was crying out for help. It took a devastation to understand the idea of mortal value, and it took a devastation to find hope.

Art by David Byrne from A History of the World (in Dingbats)

An epoch of devastations and triumphs after Leonard Bernstein made his largehearted, life-tested case against the cowardice of cynicism and Maya Angelou observed that “there is nothing quite so tragic as a young cynic, because it means the person has gone from knowing nothing to believing nothing,” Cave pits cynicism against hope:

Unlike cynicism, hopefulness is hard-earned, makes demands upon us, and can often feel like the most indefensible and lonely place on Earth. Hopefulness is not a neutral position either. It is adversarial. It is the warrior emotion that can lay waste to cynicism. Each redemptive or loving act, as small as you like… keeps the devil down in the hole. It says the world and its inhabitants have value and are worth defending. It says the world is worth believing in. In time, we come to find that it is so.

Complement with Jane Goodall on the deepest wellspring of hope, Rebecca Solnit’s classic manifesto for lucid hope in dark times, and Hermann Hesse’s response to a young man who had lost hope after World War I, then revisit Nick Cave on the paradox of creativity and poet May Sarton on the cure for despair.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.