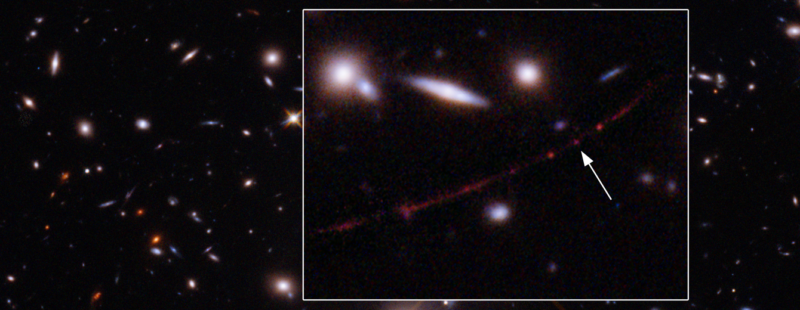

Enlarge / The string of red dots represents the area of maximum magnification, with the location of Earendel indicated by the white arrow. (credit: NASA, ESA, Brian Welch (JHU), Dan Coe (STScI) )

We don’t fully understand what the Universe’s first stars looked like. We know they must have formed from hydrogen and helium since most heavier elements were only produced after the stars formed. And we know that the lack of those heavier elements changed the particular dynamics of star formation in a way that meant the first stars must have been very large. But just how large remains an unanswered question.

Now, researchers are announcing that they might be a step closer to directly observing one of those stars. Thanks to a fortuitous alignment between a distant star and an intervening galaxy cluster, gravitational lensing has magnified an object that was present less than a billion years after typically the Big Bang. The object is likely to either be a lone celebrity or a compact system of two or three stars. And its discoverers say they have already booked time for follow-on observations with NASA’s latest space telescope.

Gravity’s lens

Lenses work by arranging materials so that light travels on a curved path through them. Gravity, which distorts space-time itself, can perform a similar function, altering space so that light travels a curved path. There possess been plenty of examples of this gravitational influences of objects in the foreground creating a lens-like effect, amplifying and/or distorting often the light from a more distant object behind them.