“We share in the slow optimistic tendency of the universe… We have life and health and wholeness on the same terms as the trees, the flowers, the grass, the animals have, and pay the same price for our well-being, in struggle and effort, that they pay. That is our good fortune.”

In those seasons of being when life boughs you down low with world-weariness, when the sun of your soul is collapsing into a black hole, when you despair of humanity’s twin capacity for inhumanity and are no longer able to hold without heartache Maya Angelou’s eternal observation that we are creatures “whose hands can strike with such abandon that in a twinkling, life is sapped from the living yet those same hands can touch with such healing, irresistible tenderness” — in those seasons of being, there is great solace in remembering that what we call human nature, with all of its terrors and transcendences and violent contradictions, is a humble subset of nature itself: In nature, where stars are always being born and die and give us life, creation and destruction are always syncopating; in nature, the seasons are always changing; in nature, every loss reveals what we are made of, and that is a beautiful thing.

Art by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

There is great comfort and calibration in trusting, not with the faith of the pious but with the faith of the naturalist, that even the bleakest seasons pass, and even the most violent forces are counterbalanced by the forces of vitality — cosmic calculus of which the very existence of life is living proof.

Such awareness is not a negation of the need for morality, of our moral calling as human beings to right the forces that violate life, but an affirmation of it — for morality would not exist if suffering did not exist.

We are human because we are sensitive to both, susceptible to both, moved by both.

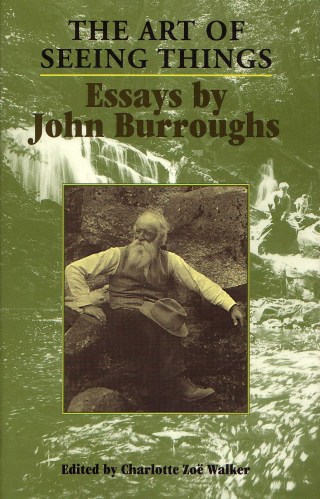

That is what the great naturalist and prose-poet of nature John Burroughs (April 3, 1837–March 29, 1921) explores in an exquisite 1904 essay reflection titled “An Outlook upon Life,” included a century later in The Art of Seeing Things: Essays by John Burroughs (public library).

In the closest Burroughs came to formulating a personal philosophy, distilling his vast view of life into a kind of credo worth borrowing, he writes:

I was born under happy stars, with a keen sense of wonder, which has never left me… and which no exaggerated notion of my own deserts. I have shared the common lot, and have found it good enough for me.

John Burroughs

Echoing the Whitman — who owes his cultural reverence to Burroughs and who, in the wake of his paralytic stroke, considered what makes life worth living and counseled to “tone your wants and tastes low down enough, and make much of negatives, and of mere daylight and the skies” — Burroughs adds:

Unlucky is the man who is born with great expectations, and who finds nothing in life quite up to the mark.

One of the best things a man can bring into the world with him is a natural humility of spirit. About the next best thing he can bring, and they usually go together, is an appreciative spirit — a loving and susceptible heart.

A century and an epoch of discoveries before physicist Freeman Dyson observed that “our universe is the most interesting of all possible universes, and our fate as human beings is to make it so,” Burroughs exclaims that this world is “a mighty interesting place to live in” and invites the reader into the cosmic reverie that seems to have been the all-suffusing atmosphere of his own life:

If I had my life to live over again, and had my choice of celestial bodies, I am sure I should take this planet, and iI should choose these men and women for my friends and companions. This great rolling sphere with its sky, its stars, its sunrises and sunsets, and with its outlook on look into infinity — what could be more desirable? What more satisfying? Garlanded by the seasons, embosomed in sidereal influences, thrilling with continents — one might ransack the heaves in vain for a better or more picturesque abode.

Art by Daniel Bruson for The Universe in Verse: My God, It’s Full of Stars.

Half a century before the Nobel-winning founding father of quantum mechanics Erwin Schrödinger’s dazzling illumination of consciousness as a function of the universe, Burroughs adds:

We may fancy that there might be a better universe, but we cannot conceive of a better, because our minds are the outcome of things as they are, and all our ideas of value are based upon the lessons we learn in this world.

More than the unsurpassable beauty of the planet, however, Burroughs celebrates the sheer sense of belonging to a world — to a totality of being across species and landscapes, a totality the German marine biologist Ernst Haeckel had given the name ecology when Burroughs was just beginning his literary life while working as a treasury clerk. He exults:

O to share the great, sunny, joyous life of the earth! to be as happy as the birds are! as contented as the cattle on the hills! as the leaves of the trees that dance and rustle in the wind! as the waters that murmur and sparkle to the sea! To be able to see that the sin and sorrow and suffering of the world are a necessary part of the natural course of things, a phase of the law of growth and development that runs through the universe, bitter in its personal application, but illuminating when we look upon life as a whole!

Art by Dorothy Lathrop, 1922. (Available as a print and as stationery cards.)

A generation after the grief-savaged Darwin solaced his personal loss in the scientific knowledge that the death of the individual is what propels the evolution of the species, and an epoch before science equipped us its cosmic consolation of what happens when we die, Burroughs adds:

Without death and decay, how could life go on? Without what we call sin (which is another name for imperfection) and the struggle consequent upon it, how could our development proceed?

[…]

Look at the grass, the flowers, the sweet serenity and repose of the fields — at what price it has all been bought, of what warring of the elements, of what overturnings and pulverizings and shiftings of land and sea… We deplore the waste and suffering, but these things never can be eliminated from the process of evolution. As individuals we can mitigate them; as races and nations we have to endure them… and the evolution of life on the globe, including the life of man, has gone on and still goes on, because, in the conflict of forces, the influences that favored life and forwarded it have in the end triumphed.

One of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s nineteenth-century astronomical drawings, observed through the era’s most powerful telescope. (Available as a print and as stationery cards, benefitting The Nature Conservancy.)

In a lovely antidote to human exceptionalism, Burroughs celebrates our shared inheritance with the rest of life, itself exceptional — a bright gift of chance against the staggering cosmic odds of nonexistence:

Our good fortune is not that there are or may be special providences and dispensations, as our [ancestors] believed, by which we may escape this or that evil, but our good fortune is that we have our part and lot in the total scheme of things, that we share in the slow optimistic tendency of the universe, that we have life and health and wholeness on the same terms as the trees, the flowers, the grass, the animals have, and pay the same price for our well-being, in struggle and effort, that they pay. That is our good fortune. There is nothing accidental or exceptional about it. It is not by the favor or disfavor of some of some god that things go well or ill with us, but it is by the authority of the whole universe, by the consent and cooperation of every force above us and beneath us.

[…]

If we or our fortunes go down prematurely beneath the currents, it is because the currents are vital, and do never and can never cease nor turn aside.

Spring Moon at Ninomiya Beach, 1931 — one of Japanese artist Hasui Kawase’s stunning vintage woodblock prints. (Available as a print.)

Rachel Carson — the twentieth century’s great prose-poet of nature, recipient of the John Burroughs Medal, the Nobel of nature writing — would echo this sentiment in her sublime meditation on the ocean and the meaning of life; James Baldwin — the twentieth century’s great prose-poet of human nature — would echo it in his classic insistence that we must “say Yes to life and embrace it whenever it is found” because “the earth is always shifting, the light is always changing, [and] the sea does not cease to grind down rock.” A century before Maya Angelou serenaded our shared destiny on this “lonely planet” adrift “past aloof stars, across the way of indifferent suns,” Burroughs adds:

Nature is as regardless of a planet or a sun as of a bubble upon the river, has one no more at heart than the other. How many suns have gone out? How many planets have perished?… She has infinite worlds left, and out of old she makes new… Nature wins in every game because she bets on both sides. If her suns or systems fail, it is, after all, her laws that succeed. A burnt-out sun vindicates the constancy of her forces… In an orchard of apple trees some of the fruit is wormy, some scabbed, some dwarfed, from one cause or another; but Nature approves of the worm, and of the fungus that makes the scab, and of the aphid that makes the dwarf, just as sincerely as she approves of the perfect fruit. She holds the stakes of both sides; she wins, whoever loses… Peace, satisfaction, true repose, come only through effort, and then not for long.

Another of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s nineteenth-century astronomical drawings. (Available as a print and as stationery cards, benefitting The Nature Conservancy.)

With this, Burroughs returns to the animating question of his reflection — what, amid the universe’s ceaseless dance of dissolution, makes human life worth living and what, amid nature’s indifference to our notions of good and evil, backbones a good life:

To have a mind eager to know the great truths and broad enough to take them in, and not get lost in the maze of apparent contradictions, is undoubtedly the highest good.

Complement with Marcus Aurelius on the good luck of your bad luck and Simone Weil on how to make use of our suffering, then revisit Mary Shelley — envisioning a twenty-first-century world savaged by a deadly pandemic, from a nineteenth-century world savaged by the decade-long Napoleonic Wars — on nature’s consolations and what makes life worth living.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.