Enlarge / Eagle Plume Tower in Bears Ears, Utah. Geologists at the University of Utah have developed a mathematical model to predict the fundamental resonant frequencies of this and similar formations based on the particular formations’ geometry and material properties. (credit: Geohazards Research Group)

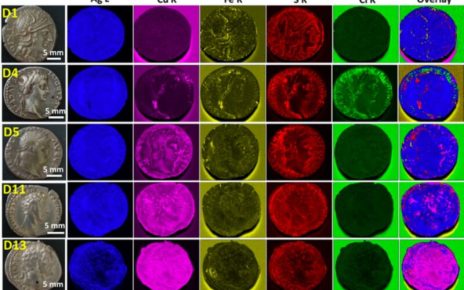

The striking red rock towers and arch formations peppered throughout Southern Utah and the Colorado Plateau are known to shake and sway in response to earthquakes, high winds, thermal stresses, and other sources of vibration, such as those from helicopters, trains, passing vehicles, and blasts. Being able to assess the stability of these structures, and detect any damage from vibrations, can be challenging. That’s why geologists have been measuring the natural frequencies of these towers for several years now.

Led by University of Utah geologist Jeff Moore, the group of geologists maintains an entire webpage devoted to its seismic recordings of the natural resonances (vibrations) that come out of the Utah red rock towers and arches. The geologists have now used that data set to develop a theory that can predict typically the frequencies at which these formations vibrate and deform, described in a recent paper published in this journal Seismological Research Letters.

Overcoming hurdles

As we’ve reported previously , understanding those dynamics is crucial to being able to predict how the structures will respond in the event associated with an earthquake or similar disruption. Yet, there haven’t been many ongoing efforts to do so over the years, despite a great deal of research on manmade civil structures. One of the major challenges has been gaining the access necessary to make those vibrational measurements in the first place. Either the formations are restricted (the better to preserve them for posterity), or it’s simply too difficult to place sensors in hard-to-reach spots on the formations.