“Those people who see clearly the necessity of changed thinking must themselves undertake the discipline of thinking in new ways and must persuade others to do so.”

The thrill of childlike wonder never left Kathleen Lonsdale (January 28, 1903–April 1, 1971), who often ran the last few yards to her laboratory and took her mathematical calculations into the maternity ward where her children were born.

The tenth child in a Quaker household without electricity, she was born in Ireland the year the Wright brothers built and flew the world’s first successful flying machine heavier than air. Her home was still lit by gas when she first began studying science — in a school for boys, because no such subjects figured into the curriculum of the local girls’ school. By the time she was a teenager, living outside London, she watched gas-filled Zeppelins rain bombs and death from the air. She watched them go down in flames, shot down by British weapons. She watched her mother cry with the knowledge that piloting them were German boys not much older than Kathleen.

Trained as a physicist, Kathleen Lonsdale went on to become the pioneering X-ray crystallographer who illuminated the shape, dimensions, and atomic structure of the benzene ring that had mystified chemists since Michael Faraday discovered benzene a century earlier. She was still in her twenties. The chemistry of benzene would come to fuel the twentieth century. J.D. Bernal — the visionary scientist who first applied X-ray crystallography to the molecules of life and whose laboratory group she joined — came to see how beneath Lonsdale’s quiet, unassuming manner lay “such an underlying strength of character that she became from the outset the presiding genius of the place.”

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale. (Photograph: Walter Stoneman. National Portrait Gallery.)

Lonsdale became the first woman tenured at London’s most venerated research university and the first female president of both the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the International Union of Crystallography.

She also became one of the twentieth century’s most lucid, impassioned, and indefatigable activists against our civilizational cult of war and the military industrial complex funding its planet-sized house of worship. When the next World Ward broke out, Lonsdale — by then one of the world’s most preeminent scientist — was imprisoned as a conscientious objector to military conscription. She went on to become one of Europe’s most influential prison reformers, having seen how the prison industrial complex — a term then yet to be coined — is the price societies governed by the military industrial complex pay for the inequalities and injustices stemming from that foundational cult.

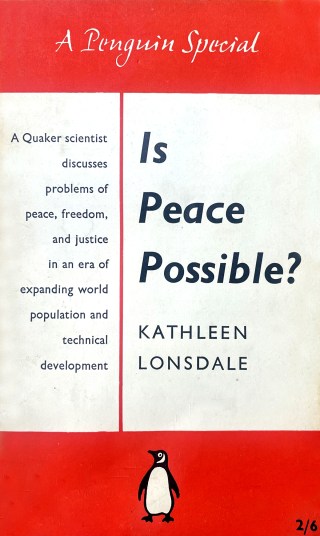

In 1957, Lonsdale wrote a slender, exquisitely reasoned and deeply felt book titled Is Peace Possible? (public library), now out of print. She writes:

History teaches us that time can bring about reconciliations that seemed at another time impossible, but only when violence has ceased, whether by agreement or through exhaustion.

Art by the American pacifist Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, written and painted in the final months of WWI. (Available as a print and as stationery cards.)

A quarter century after Einstein and Freud’s little-known correspondence about war, human nature, why we fight, and how to stop, Lonsdale challenges the misconception of pacifism as the simplistic idea that a perfect and peaceful world is merely a matter of individuals refusing to fight. “Truism based on Utopias are poor arguments,” she observes, instead invoking the style of pacifism native to the Quaker tradition and its original formulation in 1660 as the refusal to partake of “all outward wars and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatever.” Bridging the spiritual ethos of her upbringing with the scientific worldview of her calling and training, she writes:

The man or woman is sure, whether through the guidance of the Spirit of Christ or the guidance of their reasoning powers or both, that war is spiritually degrading, that it is the wrong way to settle disputes between classes or nations, the wrong way to meet aggression or oppression, the wrong way to preserve national or personal ideals: that man or woman who is sure of this must obviously take no part in war and indeed must actively oppose it. Most civilized nations are beginning to realize that there is such a thing as a genuinely conscientious objection to personal participation in war, even if they do not regard it as expedient to encourage young people to think along these lines or take this stand.

One of teenage artist Virginia Frances Sterrett’s century-old illustrations for classic French fairy tales. (Available as a print.)

With empathic sensitivity to the confusions and intuitions that lead otherwise goodhearted people to see some applications of war as justified, she adds:

Most people, however, are not sure of anything… They are not sure that it is wrong to fight, if by fighting one can alter intolerable conditions, or prevent large-scale communal crime, or get rid of a dangerous dictator before he gains too much power, or stand up to international blackmail, or ward off an armed attack. In terms of reason, they find it arguable — as it is — to say that although every possible way to avoid war must be sought, yet until men are perfect there will always be some who want to grab more than their share. They see no reason why this should be permitted if it can be prevented by the limited use of military force. They are pretty sure that it is prevented in many cases by the knowledge that force is there to stop it. For men are not perfect, but neither are they foolish enough, as a rule [with exceptions], to burgle or murder even on a national scale, if they know that they will be stopped and punished.

Citing a prominent politician who had once said to her that “pacifism is not practical politics” but “to be spiritually healthy every nation needs to have a spear-point of idealist opinion,” she dismantles the convenient illusion that pacifism is a purely ideological stance with no practical responsibilities of political participation:

The pacifist who argues that he is concerned only with principles, and that politics are not his business, is usually evading the discipline and the responsibility of hard thinking. His position is a logical one only if he does not either expect or desire the politician to put pacifist principles into practice for him. He won’t expect it, but if he does desire it then it is incumbent on him to study the world situation and try to decide for himself how it might be done, in general at least, if not in particular.

To illustrate the interleaving of lives across the artificial pickets of national borders, she looks back on the 1947 cholera epidemic that quickly came to claim five hundred lives per day in Egypt but was also quickly curbed after twenty nations cooperated on a supply line for vaccines. In a sentiment of staggering timeliness in the wake of the twenty-first century’s deadliest pandemic — which Mary Shelley anticipated two centuries ago — Lonsdale observes that “plagues are no respecters of sovereignty,” nor are the far-reaching economic, moral, spiritual, and radioactive consequences of war.

Art by Ryōji Arai from Almost Nothing, yet Everything: A Book about Water by Hiroshi Osada

In another sentiment of staggering timeliness in the aftermath of a twenty-first-century despot masquerading as a democratic ruler while erecting a physical wall on his nation’s border, and half a century before Toni Morrison lamented that in our time “walls and weapons feature as prominently now as they once did in medieval times,” Lonsdale adds:

One of the objects of military alliances and military defence seems to be the prevention of population movements, the freezing of the status quo.

It is just not possible to freeze the status quo, either nationally or internationally. One might as well try to freeze the Indian Ocean.

Writing shortly after the first test explosions of nuclear weapons in the Pacific Ocean, and shortly before Rachel Carson made ecology a household a century after it was coined with her epochal exposé on the ecosystem devastation pesticides inflict far beyond their intended locus of use, Lonsdale observes:

No nation can claim that it can do what it likes, even with its own. The air above it will move to other parts of the world. The water around it will be exchanged gradually, not only with surface waters elsewhere, but also with the waters in the depths of the ocean.

Art by Ryōji Arai from Almost Nothing, yet Everything by Hiroshi Osada

At the heart of Lonsdale’s case against war is a clarity about the dangers of relativism and transactionalism, the dangers of mistaking self-interest for moral courage:

Total disarmament would not be an extreme form of partial disarmament [but] something quite different… At present our attitude is “If you eat my grandmother, I’ll eat yours. But if you will agree not to eat my grandmother, I’ll agree not to eat yours either, but I will jolly well look out to see that you are not beginning to boil the water in the saucepan.” What we need to do is to develop a horror of cannibalism, a horror of the crime of war.

Total disarmament means not only the abolition of military organization, of armament factories, of armies, of the naval and air forces, but the re-education of men and women everywhere to abhor the idea of war… abhor war and all preparations for war, not only in one country — although some country must set an example — but in every country… abhor it so much that they were willing to accept the readjustments that the absence of war and of the sanction of force might mean. It would be absolutely necessary to be clear on that point in any large-scale effort at adult education.

Art by Edward Gorey for a special edition of Little Red Riding Hood

This is a point of great subtlety and great import, for it speaks not only to the constant threat of war looming over the world but to the ecological apocalypse looming with even greater certainty unless we re-educate ourselves. In the near-century since Lonsdale’s time, we have cannibalized our climate for the exact same reason we have failed, as a civilization and a species, to eradicate war: Most people, whatever their loftiest moral standards may be, are simply too unwilling to inconvenience themselves with the not terribly demanding readjustments of habit that a personal stance against fossil fuel or the tendrils of the military industrial complex would demand of their daily lives. We weigh political candidates by how their tax policy would impact our personal finances and not by their intended military spending. We toss our soda cans — made of the same metal as the military aircraft of WWII — into the recycling bin when we remember, and we continue to fly across the increasingly carbonic sky we share.

Art from The Three Astronauts — Umberto Eco’s vintage semiotic children’s book about world peace

With this, Lonsdale excavates the deepest stratum of the reasons for war. Military alliances and international treaties only gauze the open wound of widespread inequality and injustice that colonialism and capitalism have inflicted on our world. In a sentiment an epoch ahead of her time, she observes:

Real security can only be found, if at all, in a world without the injustices that now exist, and without arms.

Lonsdale considers how such a world might become possible:

There are two ways in which such changes might come. One is the way of the compulsion of experience, the whip and spur of historical inevitability, the coercion of facts. That is the hard and bitter way. The other is the way of foresight, of preparation, of imagination. It is also the way of moral compulsion. It may be no less hard but it is not bitter.

Half a century before Jacqueline Novogratz bridged the notions of moral imagination and moral leadership in her elevating manifesto for a moral revolution, Lonsdale laments that most people are not instinctually able to make the necessary effort of imagination, for they are too accustomed to being led by leaders too unimaginative and morally insipid, if not actively immoral. She writes:

Most people… can rise to great heights of courage and sacrifice, but not usually without leadership. Two kinds of such leadership exist. The first is leadership from above. The other is leadership from within. Very often the second does have to precede the first. Those people who see clearly the necessity of changed thinking must themselves undertake the discipline of thinking in new ways and must persuade others to do so.

Art by Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, 1919. (Available as a print and as stationery cards.)

Anticipating the world-changing power of Greta Thunberg’s generation, Lonsdale considers the members of our species best poised to think in new ways:

The new world needs much more than co-existence. It needs ways of living together peacefully and co-operatively, and these ways young people educated in the principles of peace could help find.

[…]

What is essential in the future is that every member of the family, even little children, should learn at whatever cost not to give way to wrong or to co-operate in it… It would mean also that if another nation was invaded, and not our own, the support that we could give them would be limited to moral support… unless we intend to destroy the world to prevent aggression. But moral support is powerful in proportion to the integrity of the nation that gives it.

Four years before Eleanor Roosevelt — who shared Lonsdale’s condemnation of nuclear weapons and spearheaded the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that set out to lay “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” — made her impassioned case for our personal power in world change, Lonsdale observes that creating a world without war would require as much cultural devotion and resources as planning for war took in the past. But such planning, she observes, is not the unreachable work of governments — it is the work of the people, each and every one of us, for we ourselves are the primary resource of the possible future:

If the will to plan internationally for peace were there, the mechanisms would not be far to seek. And the will that is required is that of ourselves, the ordinary people of the world, expressed urgently enough for those who govern not to be able to ignore it, even if they would.

Art from Trees at Night by Art Young, 1920s. (Available as a print.)

A surviving copy of Is Peace Possible? is well worth tracking down. (Humanistic publishers, take note: It is also well worth bringing back into the public imagination.) Complement it with Albert Camus on the antidote to violence and the great Czech dissident playwright Václav Havel — who endured multiple imprisonments by the communist government for his values of justice, humanism, and ecological consciousness, before becoming president of his liberated country — on living up to our interconnected humanity in a globalized yet divided world, then revisit E.B. White, writing in the same era as Lonsdale on the other side of the Atlantic, on nuclear weapons and what it really means to live in a peaceful world.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.