The metaphysical made physical in a symphonic celebration of imagination, collaboration, and the human heart.

“Time is a dictator, as we know it,” Nina Simone (February 21, 1933–April 21, 2003) observed in her soulful 1969 meditation on time. “Where does it go? What does it do? Most of all, is it alive?”

If time is the substance we are made of, as Borges so memorably wrote the year the teenage Eunice Waymon began studying to become “the world’s first great black classical pianist” before she made herself into Nina Simone, then there is something singularly haunting and mysterious about the fragments of substance we leave behind after time unmakes us. Their ghostly materiality might be our only real form of time travel, our only undeluded form of immortality — the ultimate evidence that time is, in the deepest sense, alive.

I remember feeling this eerie enchantment one early-autumn afternoon as I climbed the narrow wooden stairs to Emily Dickinson’s bedroom — which was also her writing room — during my long immersion in her life while writing Figuring. I ran my fingers over the smooth mahogany of the tiny sleigh bed in which she slept and dreamt and loved. I ran them over her miniature cherrywood writing desk — those seventeen square inches, on which she conjured up cosmoses of truth in hundreds of poems volcanic with beauty.

Emily Dickinson’s hair

In another season, in another city, I felt the eerie enchantment again as I beheld the small round lock of her auburn hair through the museum glass and the epochs between us — the marvel of how it was possible to feel so much by the sheer proximity to a clump of unfeeling atoms that had outlived the temporary constellation of consciousness they once animated with humanity, with poetry, with feeling. A self-conscious, shimmering strangeness.

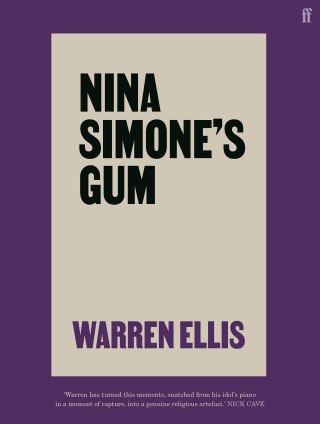

That eerie enchantment comes aglow in Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found (public library) by Australian musician and composer Warren Ellis — a strange and shimmering book, alive with the deepest questions of what makes us who we are and why we make the life-stuff we call art, using the chewing gum Ellis once pried from under Nina Simone’s piano as a lens on memory, mortality, and our search for meaning.

What emerges is something not fetishistic but belonging to the stream of time, which casts ashore the artifacts of the lives it inescapably washes away, just like it will wash away yours and mine and Ellis’s, like it washed away Nina Simone’s. This flotsam of objects — the stories they carry, the past selves they carry — becomes the only time travel available to us, mortal creatures made of dead stars in an entropy-governed universe whose fundamental laws aim the arrow of time at one destination only. These artifacts shimmer for us with meaning beyond their materiality, because somewhere in the core of our being, we recognize them as our only “bright star of resurrection.”

Warren Ellis and his first violin

Ellis — who began playing the violin at age 7, fell under the instrument’s lifelong spell after learning the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, and continued playing the same violin for twenty-one years, through elementary school and college, through busking in the streets of Europe and playing with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds — had long worshipped Nina Simone, “the divine incarnate,” whose voice seemed to carry the same cosmos of emotion that bellowed from the violin’s reanimation of Beethoven. For Ellis, the thought that his atoms would ever come in close proximity to hers seemed as fantastical as meeting Beethoven.

And then, one summer day in 1999, they did.

His longtime friend and collaborator Nick Cave — himself an uncommonly soulful and penetrating thinker about loss, memory, and transcendence — was directing London’s Meltdown Festival, and Nina Simone was to perform. Nobody yet knew it — for such is the murderous cruelty of lasts shot by time’s error — but it would be her last show in London.

Cave recounts the nested strangenesses of that fateful evening:

Nina Simone was a god to me and to my friends. The great Nina Simone. The legendary Nina Simone. The troublemaker and risk taker who taught us everything we needed to know about the nature of artistic disobedience. She was the real deal, the baddest of them all, and someone was tapping me on the shoulder and telling me that Nina Simone wanted to see me in her dressing-room.

She had summoned Cave to issue a commandment. Sitting there in her billowing white gown and Cleopatraesque metallic gold eye makeup, “imperious and belligerent, in a wheelchair, drinking champagne,” with “several attractive, worried men” lined against the wall, she looked at him “with open disdain” and declared that she wanted him to introduce her — as “Doctor Nina Simone.” (She had received her first honorary degrees in the 1970s at Amherst College, a block from Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, just as Ellis was beginning his life in music.)

Cave issued an overeager “OK!” (In my mind, he curtsied.) And so, after his introduction, the show — which would end in “mutual rapture”: the audience in a state of grateful transcendence, Doctor Nina Simone “restored, awakened, transfigured” — began with intense emotional discord.

Sitting five rows from the stage — “awestruck and glowing as if from a dream,” in his friend’s recollection — Ellis watched Nina Simone sit down at the Steinway, looking malcontented and angry and in pain, staring unsmiling at her fans while smoking her cigarette, smoking her cigarette while chewing her gum, “chewing with this look of tired defiance on her face.”

Something about that struck Ellis as absolutely fantastic. It strikes me — the gum, the poetic incongruence of it — as tangible, chewable evidence of Whitman’s eternal insight that we contain multitudes, perhaps all the more multifarious in proportion to a person’s genius, which is always the product of greater interior complexity. Ellis recounts what happened next:

The crowd got to its feet when “Dr Nina Simone” came from Nick’s mouth and she moved onto the stage slowly. People were clapping, crying, screaming, ecstatic. I had never felt energy like that in a room. It was unfathomable to think we were in her presence. Those moments you don’t believe are real. When you know life will never be the same after.

[…]

With great difficulty she walked to the front of the stage and she just put her clenched fist up in the air and just went, “Yeah!” Just like that. And I think there was this kind of reply, like a “yeah!” back, back to her. I remember nothing came out of my mouth as I attempted to reply. And then she did it again: “Yeah.” The sound of two thousand people gulping and their breath being sucked out of them.

Nina Simone at the Meltdown Festival, London, July 1, 1999. (Photograph: Bleddyn Butcher.)

There is no romanticizing the fact that this person of staggering genius self-medicated her longtime depression with substances, the abuse of which had caught up to her in a grim way by those final years of her life — a life of greatness staggered short by those very crutches for suffering. (Champaigne, cocaine, and sausages were among the things she demanded be brought to her backstage.) And yet there she was, majestic in her genius, unsaved by her genius, chewing her gum. With the empathetic poetry of perspective that underscores his book, Ellis writes:

I remember reading about a moment in her life in the mid-sixties when she got really depressed. Someone told her, “You know, you’re carrying the weight of everybody on your shoulders. It’s normal that you should crack up.” That we were about to see her perform in 1999 was a miracle.

As soon as she sat down at the Steinway, Nina Simone took the gum out of her mouth and stuck it under the piano; as soon as she walked off the stage, transformed and triumphal, Ellis leapt onto it as if in a trance, pried the gum from the piano, wrapped it in the abandoned towel she had used to wipe her sweat, and leapt off. He stuffed his strange bounty into a bright-yellow Towel Records bag and went back to his hotel.

He began carrying it with him on tour, in the briefcase — that was the era — containing his “portable shrine,” alongside a 2B Staedtler pencil and a theosophical edition of Notes on the Bhagavad-Ghita, a poem from a friend and a green ballpoint pen from a Munich hospital, a red Japanese address book and a cross he had given his mother, which she had given back to him. Once or twice, perhaps the way one draws strength from an amulet, he looked at the gum in his hotel room, but he never touched it or removed it from the towel. Its existence remained largely a secret — partly the sanctity of the private talisman, partly his self-conscious sense that nobody else would care about Nina Simone’s chewed gum.

And then, 9/11 happened. With his big beard, odd gear, and time-traveler garb, Ellis became the subject of constant bomb checks. Between the sniffer dogs and the general chaos, his strange relic no longer seemed safe in its towel and Tower Records bag. He decided to safekeep it at home. It lived for a while atop his own piano, but that began feeling too unsafe. He stuffed it in a vase in the window above the piano, but remained uneasy. He disassembled the piano and tucked it behind the soundboard.

While touring, he began having panic attacks that something would happen to the gum, even though his watchful wife knew exactly where the gum was and exactly what it meant to her husband.

When Ellis built himself a home studio, complete with a tiny shrine, he placed the Towel Records bag there, alongside a black-and-white photograph of his kids playing in the garden and a bust of Beethoven. Eventually, that too came to feel unsafe — he moved the gum to a wooden chest he had built in the attic and tucked it away along with his tax returns.

It remained there for many years, until Nick Cave asked his friend whether he still had the gum he had snatched from Nina Simone’s piano that strange and transcendent midsummer night in 1999.

Two decades later, with Nina Simone gone to canon and stardust, her gum appeared inside a velvet-lined, temperature-controlled wood-and-glass box on atop a marble pedestal at the Royal Danish Library, part of Stranger Than Kindness — Nick Cave’s Copenhagen exhibition turned book, exploring “the wild-eyed and compulsive superstructure” of creative influences beneath any artistic body of work, a subject he has contemplated with uncommon poetry of insight.

Viewed from some distance, the miniature pedestal rises in its warm-lit case like a votive on the altar of some alien temple.

Ellis writes:

Something shifted when others became aware of the gum’s existence. I thought about how many tiny secrets there must be out there in the universe waiting to be revealed. How many people have secret places with abandoned dreams, full of wonder.

Except the relic on the marble pedestal was not Nina Simone’s gum, at least not exactly, and the story of its notness made it all the more a relic:

After Cave asked about the gum, Ellis had gone into the attic, retrieved the yellow Tower Records bag, unfurled the towel, and looked at the gum for the first time in many years — there it was, unaltered by time or memory, with Nina Simone’s toothprint still exactly as he recalled it. He reflects:

The idea that it was still in her towel was something I had drawn strength from. Like the last breath of Thomas Edison contained in a sealed test tube, kept in the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan. As Edison lay dying, Henry Ford telephoned Edison’s son and asked if he could capture the great man’s last breath. So he placed a rack of test tubes by the bed and stoppered them when Edison slipped this mortal coil. Unseeable, untouchable, the imagination that was activated by nothing. That nothing could engage the imagination. Communal imagination. That nothing could be everything.

Followed back far enough, everything that moves us, everything we hold dear with a ferocity of feeling, is at bottom a hedge against our own mortality. Ellis realized that once his own atoms constellate a living person no more, this nondescript piece of chewing gum wrapped in a rag inside a twenty-year-old plastic bag would end up in a garbage bin — unless others become aware of its origin and significance, forming a chainlink of custodians to ensure the survival of this relic with meaning far beyond its materiality.

The notion of getting the gum out of his orbit, into proper stewardship, into the public imagination, suddenly seemed like a duty. Recognizing that the polymers and resins laced with food-grade softeners were not equal to the task of historical preservation, Ellis decided to make a cast of it — an idea inspired by plaster-casts of hands he had seen in while wandering into Melbourne’s antiquarian fair looking for one of the fourteen surviving copies of William Blake’s America a Prophecy. (Such is the superstructure of influences and creative catalysts.)

Nervous not to “let the gum down as custodian” if anything went awry in the casting process, Ellis set out to find a collaborator he could entrust with this improbable miniature mausoleum. Even this becomes a meta-meditation on a fundament of art and the creative process, consonant with my own credo that so much of life is a matter of finding the people who magnify your spirit. He writes:

Finding the right people to work with. That’s the thing, isn’t it? How does that happen? What draws us to people? Or them to us? This trust that is needed for collaborations to exist. This beautiful fragile moment each creation has to pass.

A Rube Goldberg machine of trusts follows, beginning with his younger brother’s childhood best friend — an artist from an old gold mining town in rural Australia that greets visitors with a replica of the largest gold nugget ever found there: a colossal 70-kilogram lump of precious metal forged billions of years ago in the core of some dying star as it collapsed into a black hole.

Welcome Nugget, Ballarat, Victoria.

As a boy, Ellis had marveled at the nugget from his bike; as a grown man, his mind’s eye — that prism of memory and association — brought back the gold nugget as a magnified version of Nina Simone’s gum, giving him the idea of finding a jeweler to make the cast.

After some contemplation, his childhood friend sent Ellis to the perfect person for the odd job. In a London downpour, completely soaked and so anxious he nearly turned around to go home, Ellis arrived at the doorstep of the expat New Zealander Hannah Upritchard. She remembers him turning up in his wool trousers and waistcoat, “a custodian of something big” — something big she was about to extract from a twenty-year-old towel using needlepoint tweezers and a fine scalpel. Everything about this surgery on the toothprinted soul made Ellis shudder. Given the delicate object and the material science involved, it would take a rare master to cast the relic without destroying it. Here he was putting his panicked trust in a total stranger:

Already aware I looked foolish enough as it was, I could feel my ears pop and the sound become muffled, that sensation when you put your head underwater and your heartbeat becomes an industrial pump… I was sort of hovering over her as if she was handling a newborn baby. Trying to be cool and totally not. I was instantly soaked in perspiration and I undid the fourth button on my best floral shirt. Three buttons is day time, four is for concerts. I really wasn’t helping the moment so I sat down on the wooden kitchen bench and watched her.

Hannah Upritchard at work

Frenzied with the knowledge that this stranger’s steady hands were the first to touch the gum since Nina Simone’s, Ellis felt an edge of sorrow that any touch might break the spell:

Her spirit existed in the space between the gum and the towel. That concert was in the gum. That transcendence. That transformation. It took me some time to come to terms with the fact that this would be broken.

When she asked him to hold it, he declined and left, leaving behind his fragile trust. Having sensed his unease, she sent him an assuring photograph of the gum sealed away in a neatly labeled empty marmalade jar, tucked into the safe storing the precious stones she works with. “Don’t worry, Warren. I get it,” the message read.

This simple kindness, too, becomes part of the way in which this seemingly foolish project is at heart a miniature of the largest truths about art and the creative spirit. Ellis reflects:

Those three words, “I get it.” It’s that moment when other people give you the confidence to trust and let go. Permission to let go. Often it is unspoken. It is understood telepathically. In the studio I’ve experienced this throughout my whole creative life, those moments when people reassured you with the confidence that allowed you to work to your greatest potential. Everyone getting it. To this day I haven’t touched the gum. I haven’t seen it physically since, except in the photo updates of its transformation. The beauty of others taking the baton.

The assurance was soon amplified by Upritchard’s conscientious craftsmanship and her devotion to rendering the perfect cast, both physically and symbolically. After considering the two possible approaches to casting — making a mould, or scanning the gum and having it 3D-printed — she felt the computerized option was “too impersonal and dismissive” to properly honor this strange and tender relic. Instead, she settled on “something cruder but also more honest and human.”

Warming a walnut-sized ball of pink Super Sculpy with her hands, she shaped into two tiny hemispheres and gently pressed the twenty-year-old gum between them.

Using this mould, she spent weeks perfecting the copy in blue wax, then cast it in silver.

Ellis finds the poetry in this material feat:

The metaphysical made physical… The gum was the relic laid in the foundations of a monument being built through love and care, with Nina Simone as the goddess over all.

The photographs of the process reminded Ellis of Emily Dickinson’s herbarium, a facsimile of which he owns and cherishes. (As do I, having turned it into a collaborative music-consecrated celebration of poetry and science.)

Still from Bloom — an animated adaptation of Emily Dickinson’s poetry set to music by Joan As Police Woman, featuring specimens from the poet’s herbarium.

Once the initial cast was made and the spell unbroken, Ellis went on to collaborate with other artists, turning the gum into relics both private and public: a silver ring, a white gold ingot, and finally a sculpture the size of the human heart — the same size and shape as the human fist, the fist Nina Simone had raised that long-ago summer night hard with her sorrow and her power, chewing her gum.

Once again, Ellis zooms out of the particulars and into the universals of creative collaboration:

I became aware that the gum was bringing out the best in people. It’s always been other people who have brought that potential out of me. I’m the inverse of the gum somehow. It’s about connection. People who have encouraged me to be the best I can, allow me to go unrestrained. Letting ideas take flight. Letting me take flight. The wonder of playing in a band. Making music with people. I was watching something unfold in a visual way, that I sensed often as an abstract or internalised concept… I could see a process happening in front of me that was familiar. An idea coming to life. Like a song or piece of music. People rallying around to do what was best for the song. Holding it aloft.

Something about this entire endeavor is making me think of The Golden Record — Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan’s poetic gesture to the cosmos, which traveled aboard the Voyager spacecraft into the great unknown. The Golden Record had two purposes. The overt scientific one, which got the project its NASA greenlight, was an effort to compress, encode, and transmit information about our world to another — an aim both ambitious and naïve, for the probability of this human-made artifact reaching another life-form in the vast expanse of austere spacetime, intersected with the probability of that potential life-form having the tools and consciousness capable of deciphering the disc, approximates zero.

But The Golden Record had a second aim — a poetic purpose that remains, in history’s hindsight, its primary: In the middle of the Cold War, in the aftermath of two World Wars and the assassinations of Dr. King and JFK and Gandhi, here was something holding a mirror up to humanity, inviting us to reflect on who we are and what we stand for, reminding us of our capacity for beauty and transcendence encoded in millennia of music from across our indivisible Pale Blue Dot — that ultimate poetic truth of what makes us human. What Ellis makes of Nina Simone’s gum — cast in gold, imprinted with the spirit from which her music sprang, fisted with a century’s struggles and triumphs, heartened by the timeless human capacity for transcendence — makes of it a sort of Golden Record for our own time.

In the final pages of Nina Simone’s Gum, Ellis captures this deepest dimension of his improbable and lovely personal obsession turned collaborative celebration:

The beautiful thought remains with me, that the big story of this gum is entirely projected by people. Their compassion. It is within them, springing from the purest of places. The imagination. The divine. The human heart. Everything and nothing.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.