The number of human-made existential risks has ballooned, but the most pressing one is the original: nuclear war.

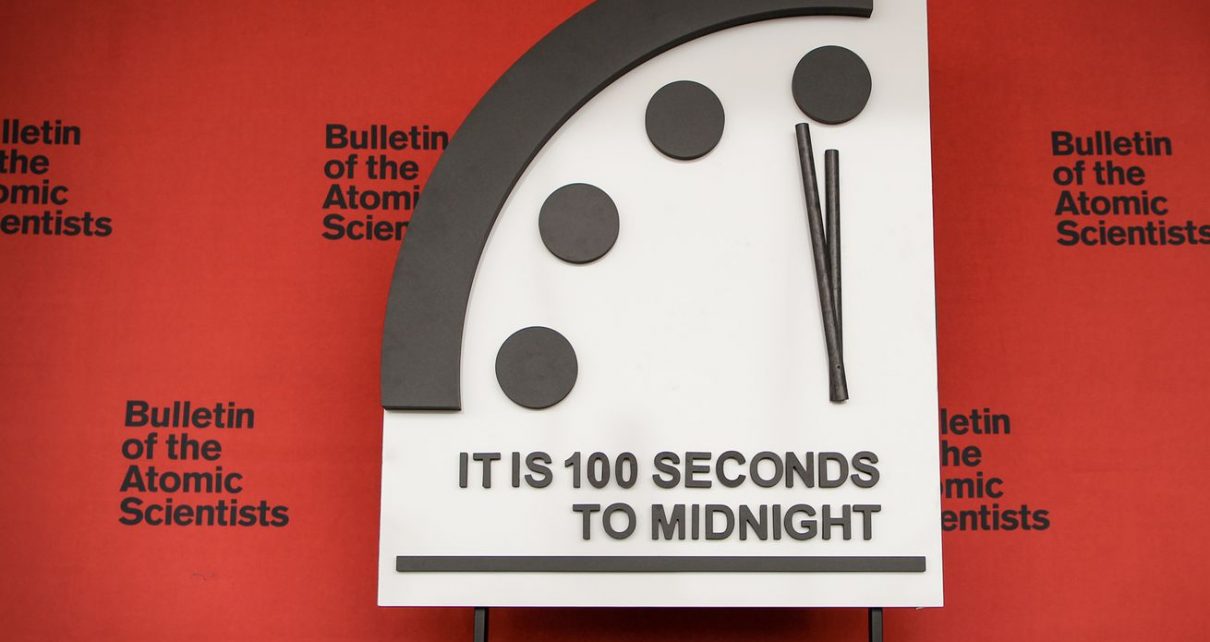

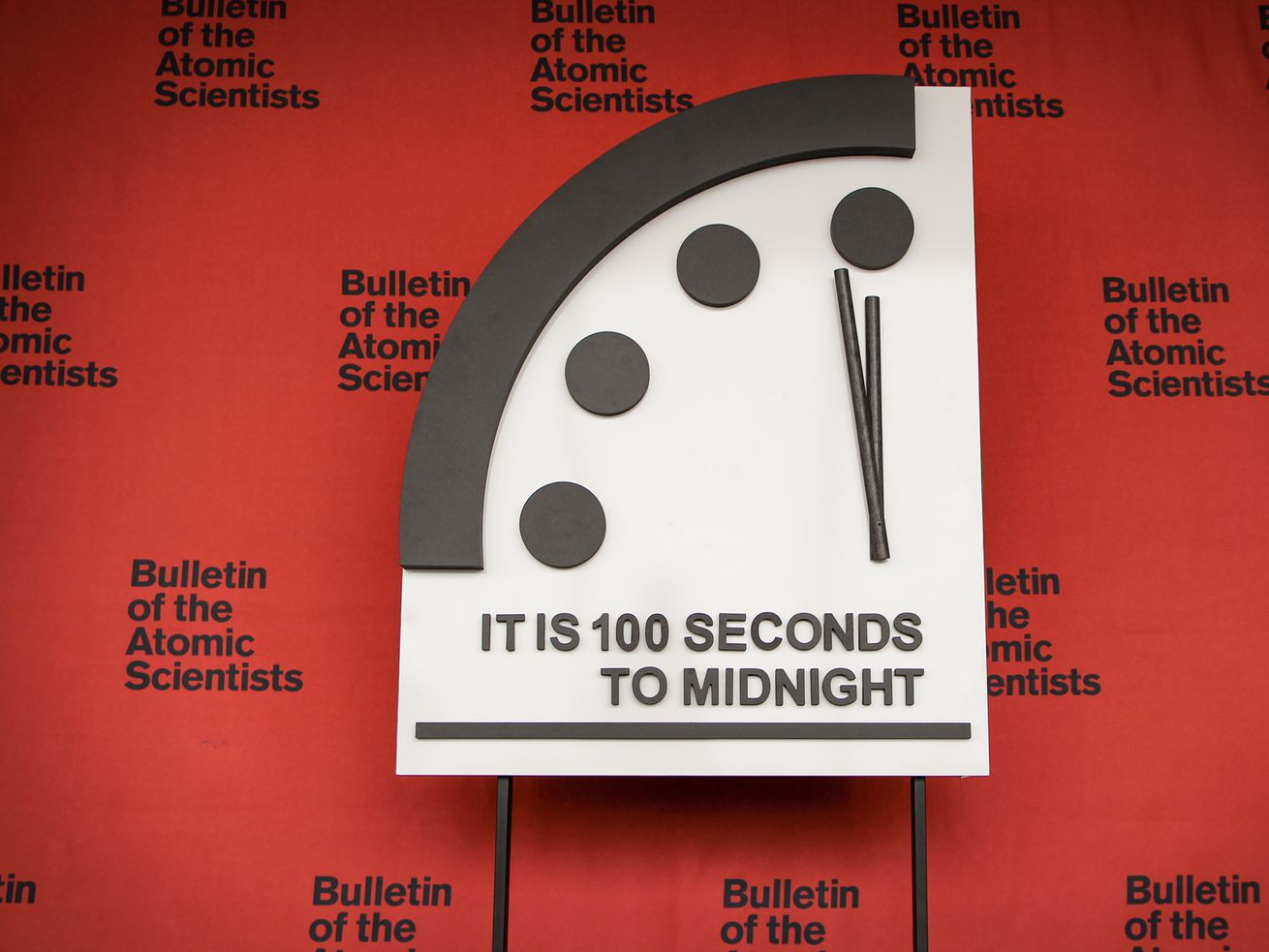

One hundred seconds to midnight. That’s the latest setting of the Doomsday Clock, unveiled yesterday morning by the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

That matches the setting in 2020 and 2021, making all three years the closest the Clock has been to midnight in its 75-year history. “The world is no safer than it was last year at this time,” said Rachel Bronson, the president and CEO of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “The Doomsday Clock continues to hover dangerously, reminding us how much work is needed to ensure a safer and healthier planet.”

As for why the world is supposedly lingering on the edge of Armageddon, take your pick. Covid-19 has amply demonstrated just how unprepared the world was to handle a major new infectious virus, and both increasing global interconnectedness and the spread of new biological engineering tools mean that the threat from both natural and human-made pathogens will only grow. Even with increasing efforts to reduce carbon emissions, climate change is worsening year after year. New technologies like artificial intelligence, autonomous weapons, even advanced cyberhacking present harder-to-gauge but still very real dangers.

The sheer number of factors that now go into Bulletin’s annual decision can obscure the bracing clarity that the Doomsday Clock was meant to evoke. But the Clock still works for the biggest existential threat facing the world right now, the one that the Doomsday Clock was invented to illustrate 75 years ago. It’s one that has been with us for so long that it has receded into the background of our nightmares: nuclear war — and the threat is arguably greater at this moment than it has been since the end of the Cold War.

The Doomsday Clock, explained

The Clock was originally the work of Martyl Langsdorf, an abstract landscape artist whose husband Alexander had been a physicist with the Manhattan Project. He was also a founder of the Bulletin, which began as a magazine put out by scientists worried about the dangers of the nuclear age and is now a nonprofit media organization that focuses on existential risks to humanity.

Martyl Langsdorf was asked to design a cover for the magazine’s June 1947 issue. Inspired by the idea of a countdown to a nuclear explosion, Langdorf chose the image of a clock with hands ticking down to midnight, because — as the Bulletin’s editors wrote in a tribute to the artist — “it suggested the destruction that awaited if no one took action to stop it.”

As a symbol of the unique existential peril posed by thousands of nuclear warheads kept on a hair trigger, the Doomsday Clock is unparalleled, one of the 20th century’s most iconic pieces of graphic art. It’s been referenced in rock songs and TV shows, and it adorned the cover of the first issue of the Watchmen graphic novel series.

Its value is its stark simplicity. At a glance, anyone can see how close the Bulletin’s science and security experts, who meet twice a year to determine the Clock’s annual setting, believe the world is to existential catastrophe. The Clock may be wrong — predicting the apocalypse is a near-impossible task — but it cannot be misread.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23184503/GettyImages_615303584.jpg) Corbis via Getty Images

Corbis via Getty ImagesSince its introduction 75 years ago, the hands of the Clock have moved backward and forward in response to geopolitical shifts and scientific advances. In 1953, it was set to two minutes to midnight after the U.S. and Soviet Union both tested thermonuclear weapons for the first time; in 1991, after the collapse of the USSR and the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, it was moved back to 17 minutes to midnight, the furthest its been to 12 in its history.

In 2018, thanks to what the Bulletin’s experts called a “breakdown in the international order” of nuclear actors and the growing threat of climate change, it was moved to 2 minutes to midnight and has been at 100 seconds since 2020.

You may begin to notice the problem here. The metaphor of a clock provides the clarity of a countdown, but the closer the hands get to midnight, the more difficult it is to attempt to accurately reflect the small changes that could push the world closer or further from doomsday.

Nor does it help that beginning in 2007 the Bulletin expanded the Clock to include any human-made threat, from climate change to anti-satellite weapons. The result is a kind of “doomsday creep,” as dangers that are real but unlikely to bring about the immediate end of human civilization — and which fit in poorly with the original metaphor of a clock — muddy its message.

It’s also difficult to square a clock ticking ever closer to midnight with the fact that human life on Earth, broadly defined, has been getting better over the past 75 years, not worse. Even with the Covid-19 pandemic, the growing effects of climate change, and whatever might be brewing in an AI or biotech lab somewhere, humans are far healthier, wealthier, and — at least on a day-to-day basis — safer in 2022 than they were in 1947, and odds are that will still be true in 2023 regardless of the Clock’s next annual setting.

This is the paradox of life in the age of existential risk — the sheer number of ways that we can cause planetary catastrophe can make it feel as if it’s nearly midnight, but compared to how life has been through most of human history, we’re living under the noonday sun.

The one event that could change that instantly is the existential threat that the Doomsday Clock was originally designed to convey: nuclear war.

Tick, tick, tick

There’s a virtual reality program designed by security researchers at Princeton University that’s been making the rounds in Washington over the past month.

Users don VR goggles and are transported to the Oval Office, where they play the role of the American president. A siren goes off and a military official transports you to the Situation Room, where users are confronted with a horrifying scenario: early warning sensors have detected the launch of 299 nuclear missiles from Russia that are believed with high confidence to be on a path to the American mainland and its ICBM sites, as Julian Borger describes in a recent Guardian piece.

An estimated 2 million Americans will die. As president, you have fewer than 15 minutes to decide whether the attack is real and whether to launch American ICBMs in response before they are potentially destroyed on the ground.

That’s a true ticking clock, and while it might feel like a throwback to Dr. Strangelove, it’s one that could still take place at any minute of any day. Though global nuclear arsenals are far smaller than they were in the darkest days of the Cold War, there are still thousands of operational nuclear warheads, more than enough to cause catastrophe on an unimaginable scale.

And while earlier this month the five permanent members of the UN Security Council put out a joint statement affirming that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” — words first said by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985 — what’s actually happening on the ground is making that horrifying VR simulation more likely, not less.

A possible Russian invasion of Ukraine could realistically result in a conventional ground war fought on European soil, and it raises the risk of conflict between the US and Russia, which together possess most of the world’s remaining nuclear arsenal. Russia has hinted at the possibility of deploying nuclear weapons close to the US coastline, which would further reduce the warning time after launch to as little as five minutes, while Russian media has made claims that the country could somehow prevail in a nuclear conflict with the US.

Washington is pursuing a modernization of the US nuclear arsenal that could cost as much as $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years, while Moscow undertakes its own nuclear update. China is reportedly expanding its own nuclear arsenal in an effort to close the gap with the US and Russia, even as tensions grow over Taiwan.

The risk of a nuclear conflict is “dangerously high,” Jon B. Wolfsthal, a senior adviser at the anti-nuclear initiative Global Zero and the former senior director for arms control and nonproliferation at the National Security Council, wrote recently in the Washington Post.

The result of such a war would be as predictable as it is unthinkable. The heat and shockwave from a single 800-kiloton warhead, which is the yield of most of the warheads in Russia’s ICBM arsenal, above a city of 4 million people would likely kill 120,000 people immediately, with more dying in the firestorms and radiation fallout that would follow.

A regional or even global nuclear war would multiply that death toll, collapse global supply chains, and potentially lead to devastating long-term climatic change. In the worst-case scenario, as Rutgers University environmental scientist Alan Robock told Vox in 2018, “almost everybody on the planet would die.”

And unlike the other human-made threats the Doomsday Clock now aims to capture, it could unfold almost instantly — and even by accident. Multiple times during the Cold War technical glitches in the machinery of nuclear defense nearly led the US or the USSR to launch their missiles by mistake, and as the VR simulation demonstrates, the sheer speed of a nuclear crisis leaves very little room for error when the clock is ticking.

Moving away from midnight

As long as nuclear weapons exist in significant numbers, they present an existential threat to humanity. Unlike other disruptive technologies like AI or biological engineering, or even the fossil fuels that are the chief driver of climate change, they have no benign side. They are merely weapons, weapons of unimaginably destructive power, whether or not they inspire the dread they once did.

Yet we’ve survived the nuclear age so far because we’ve had the wisdom — and the luck — not to use them since 1945, and more can be done to ensure that remains the case.

Last year the US and Russia extended the New START nuclear weapons treaty, which put limits on the size of each nation’s deployed nuclear arsenal, for another five years, pausing the erosion of the post-Cold War arms control regime and giving diplomats more time to negotiate tighter limits in the future.

The US and Russia also agreed to begin new sets of dialogues on how to better maintain nuclear stability in the future, and the White House is preparing a Nuclear Posture Review that could see the US specifically pledge not to use nuclear weapons first or in response to a conventional or cyber conflict, which could help reduce the chances of a renewed nuclear arms race. Fifty-nine nations have signed onto an international treaty calling for a global ban on nuclear weapons (though none of the signatories are nuclear powers themselves).

While it will reliably continue to be set every year — at least until midnight really does strike — the Doomsday Clock may have outlived its meaning as a symbol of existential risks in a rapidly changing world where the dangers and benefits of new technologies are so co-mingled. But as a warning for the original human-made catastrophic threat, the Doomsday Clock can still tell the time — and it may be later than we think.

A version of this story was initially published in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here to subscribe!