“Doing and making are acts of hope, and as that hope grows we stop feeling overwhelmed by the troubles of the world. We remember that we — as individuals and groups — can do something about those troubles.”

When Matthew Burgess was an eleven-year-old already feeling other in the suburban Southern California of his childhood — long before he became a poet and a public school art teacher, before he made a bicontinental home in Brooklyn and Berlin with his husband — he was captivated by a tiny bright-spirited rainbow on a postage stamp that appeared on the television show The Love Boat. It was the now-iconic 1985 USPS Love stamp — a miniature of the largest copyrighted artwork in the world: the colossal rainbow swash painted on a Boston gas storage tank in 1971 by Corita Kent (November 20, 1918–September 18, 1986) — the radical nun, artist, teacher, social justice activist, and long-undersung pop art pioneer, who inspired generations of makers with her 10 rules for learning and life, collaborated frequently and dazzlingly with poets, believed that “the person who makes things is a sign of hope,” and made her art and her life along the vector of this belief.

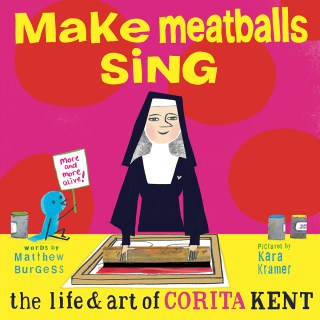

This sentiment — the most precise and poetic summation of Sister Corita’s credo — is the epigraph that opens Burgess’s loving picture-book biography Make Meatballs Sing: The Life and Art of Corita Kent (public library), created in collaboration with the Corita Art Center and illustrated by artist Kara Kramer with patterned, textured, sensitive vibrancy consonant with Corita’s art spirit and sensibility.

Doing and making are acts of hope, and as that hope grows we stop feeling overwhelmed by the troubles of the world. We remember that we — as individuals and groups — can do something about those troubles.

Emerging from these tender pages is an activist who devoted her life to fighting with fierce gentleness and generosity of soul for justice and peace in every form, from civil rights to nuclear disarmament; a rebel who subverted commerce for creativity, turning a corporate slogan (for Del Monte tomato sauce) into a clarion call for the the power of art to constellate the ordinary with wonder (which lent the book its title); a visionary who subverted the outdated dogmas of the very institution she served to effect landmark reform within the Catholic Church and to engage the secular world with the creative life of the soul; a teacher who helped her students overcome the self-consciousness and overthinking that stifle creativity by fusing play and work through her quirkily titled, ingeniously deployed process of PLORKing; an artist who became a patron saint of noticing, of paying closer attention to the world as the only means of loving it more fully — something Corita herself captured in an essays on art and life:

Poets and artists — makers — look long and lovingly at commonplace things, rearrange them and put their rearrangements where others can notice them too.

We meet Corita before she was Corita — little Frances Elizabeth Kent, growing up in Iowa, full of warm and wakeful wonder at the world — and we see her discover art as a portal of connection to this living, loving world.

And then, at eighteen, Frances astonishes everyone in her world with the decision to join the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart, becoming Sister Mary Corita Kent.

We watch her learn art history from the elder nun heading the Immaculate Heart art department and learn screen-printing from the Mexican printmaker María Sodi de Ramos Martínez, to whom one of Corita’s students had introduced her.

We see her transform the annual Mary’s Day religious procession into a community festival welcoming believers and the rest of us alike.

We see her teach kids the power of art to magnify happiness, and we see her use that power to stand up for the civilizational foundations of happiness — peace and justice — with her own art.

We leaf through the decades of her extraordinary life as she presses against the status quo in every guise with the gentle paint-stained hand of art and love: There she is, yielding protest signs with a radiant smile; there she is, on the cover of Newsweek as a modern hero of art and justice, earning her nation’s affection and her Archbishop’s wrath.

And then, astonished again, we watch her make the decision at age fifty to leave the church, move to Boston, and devote herself fully to art and activism.

There, she paints her colossal rainbow of love; there, she makes her iconic love your brother print shortly after the assassination of Dr. King.

Curiously, delightfully, Burgess did not arrive at the idea for this tribute of a book through his childhood encounter with Corita’s art. In a touching testament to the breadth of Corita’s creative ecosystem, he arrived at it through a sidewise strand unspooling from his debut children’s book, also a picture-book biography of one of his artistic heroes — the wondrous Enormous Smallness: A Story of E. E. Cummings.

Upon its publication, Burgess learned from his cousin’s partner — a historian then working on a retrospective of Corita’s work at the Harvard Art Museum — that Corita had greatly admired Cummings and incorporated lines from his poems into her prints. (It is hardly surprising that a woman of such countercultural courage and fierce daring found resonance with the poet who had built his own life upon the credo that “to be nobody-but-yourself — in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else — means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight.”)

“Down the rabbit hole I happily tumbled,” Burgess recounts of immersing himself in the wonderland of Corita’s world — and so the book was born.

Couple Make Meatballs Sing with Burgess’s equally loving picture-book biography of another of his artistic heroes — Drawing on Walls: A Story of Keith Haring — then revisit this ever-growing reliquary of excellent picture-book biographies of cultural heroes.

Illustrations by Kara Kramer courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books. Photographs by Maria Popova.

donating = loving

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

newsletter

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.