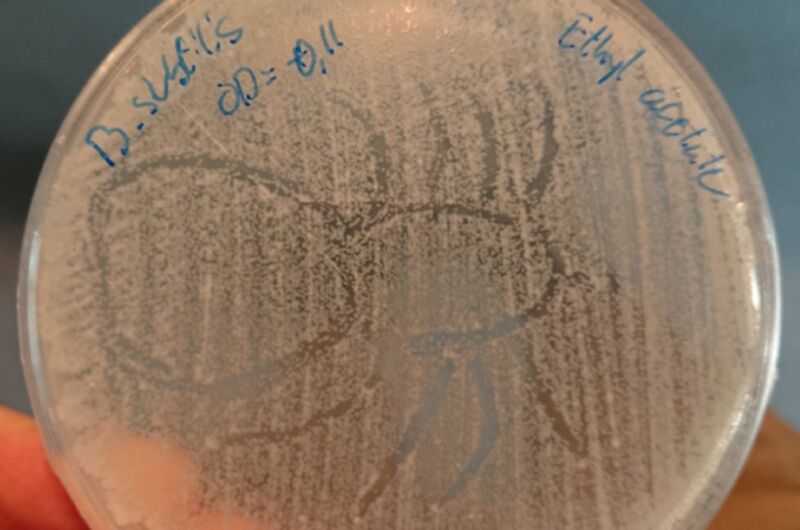

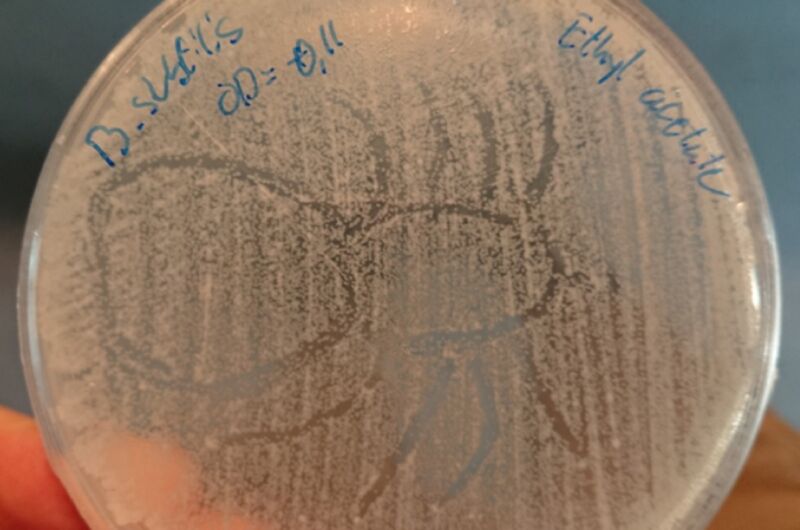

Enlarge / A new study found that ethyl acetate and other solvents typically used to study the antimicrobial properties of spider silk can inhibit bacterial growth. So prior studies finding such evidence may be methodologically flawed. (credit: Simon Fruergaard/CC BY-SA)

Ancient Greeks and Romans are said to have treated wounds suffered in battle with poultices made of spider silk, believing the silk had healing properties, as well as using it to treat skin lesions and warts. There have also been reports of people in the Carpathian Mountains using spiderwebs as bandages and doctors of ages past sometimes prescribed placing silk cocoons on infected teeth.

This notion that spider silk might have antimicrobial properties—making it a kind of “webiccillin”—has been the focus of numerous studies over the last decade in particular, with conflicting results. Some found evidence of antimicrobial activity, while others did not. Now researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark have produced the strongest case yet against spider silk’s rumored healing properties, according to a recent paper published in the journal iScience. The authors suggest that prior positive results are the result of either bacterial contamination, or the use of solvents in the experiments that have antimicrobial properties.

“Spider silk has always been admired and almost has a mythical status,” said co-author Trine Bilde, a biologist at Aarhus University. “It’s one of these myths that seems to have become ‘established’ by ‘belief’ and not by strong empirical support.”