“You must be vulnerable to be sensitive to reality. And to me being vulnerable is just another way of saying that one has nothing more to lose.”

Self-knowledge might be the most difficult of life’s rewards — the hardest to earn and the hardest to bear. To know yourself is to know that you are not an unassailable fixity amid the entropic storm of the universe but a set of fragilities in constant flux. To know yourself is to know that you are not invulnerable.

The honest encounter with that vulnerability is the wellspring of art: Every artist’s art is their coping mechanism for the extreme sensitivity to aliveness that we call beauty — the transcendent and terrifying capacity to be moved by the world, to let something outside us stir deeply something within us. All great art — and only honest art can be great — is therefore the work of vulnerability and all integrity the function of fidelity to one’s fragilities.

That is what Bob Dylan (b. May 24, 1941) addresses with his penetrating poetics of insight in a 1977 conversation with Jonathan Cott — that uncommonly sensitive and erudite investigator of uncommon minds.

Bob Dylan (Library of Congress)

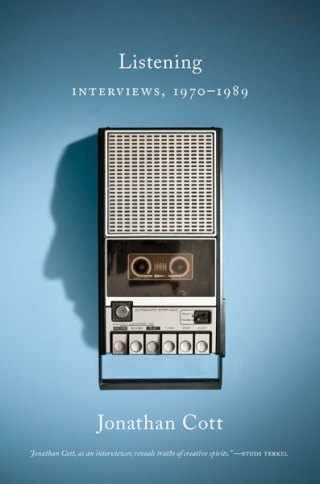

Cott prefaces the conversation, included in his collection Listening: Interviews, 1970–1989 (public library), with a soulful and percipient encapsulation of Dylan’s gift:

His songs are miracles, his ways mysterious and unfathomable. In words and music, he has reawakened, and thereby altered, our experience of the world. In statement (“He not busy being born is busy dying”) and in image (“My dreams are made of iron and steel / With a big bouquet / Of roses hanging down / From the heavens to the ground”) he has kept alive the idea of the poet and artist as vates — the visionary eye of the body politic — while keeping himself open to a conception of art that embraces and respects equally Charles Baudelaire and Charley Patton, Arthur Rimbaud and Smokey Robinson.

Dylan’s virtuosity with the mysterious and the miraculous has always sprung from his ethos of placing the unconscious mind at the center of creativity. In discussing his film Renaldo and Clara — which Dylan describes as being about integrity, about “naked alienation of the inner self against the outer self” — he tells Cott:

Human emotions are the great dictator.

[…]

You can’t be a slave to your emotions. If you’re a slave to your emotions you’re dependent on your emotions, and you’re only dealing with your conscious mind… You have to be faithful to your subconscious, unconscious, super-conscious — as well as to your conscious. Integrity is a facet of honesty. It has to do with knowing yourself.

True integrity necessitates the honesty of vulnerability — that great valve between us and the world, through which reality rushes into the chamber of our being and art pours out. Dylan observes:

You must be vulnerable to be sensitive to reality. And to me being vulnerable is just another way of saying that one has nothing more to lose. I don’t have anything but darkness to lose. I’m way beyond that.

Bob Dylan by Milton Glaser, 1967.

When the conversation turns to humanity’s greatest spiritual sages — the teachers from various traditions best able to access and teach the eternal truths — Dylan counters Cott’s observation that “they speak and teach with more emotion,” redoubling his defiance of feeling as an organizing principle for truth:

I don’t believe in emotion. They use their hearts, their hearts don’t use them.

A generation after Aldous Huxley reverenced music as the great illuminator of the “blessedness lying at the heart of things,” Dylan exalts music as a supreme instrument of revelation: its inherent honesty, its elemental fidelity to truth — the temporal and the eternal, the personal and the universal:

Music is truthful… Music attracts the angels in the universe.

It may be that Bob Dylan is the Bach of our time — the rare vessel for universal truth, whose music contains “the ultimate expression of anything and everything.”

Complement with three centuries of uncommon minds on the singular power of music and Nick Cave on music, feeling, and transcendence, then revisit psychologist Erich Fromm on vulnerability as the key to our sanity, philosopher Martha Nussbaum on how to live with our human fragility, and philosopher-poet Kahlil Gibran on the courage to know yourself.

donating = loving

For 15 years, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month to keep Brain Pickings going. It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your life more livable in any way, please consider aiding its sustenance with donation.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.