How American meddling shaped life in Afghanistan.

The United States’ decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan closes a 20-year chapter between the two countries. But US intervention in Afghanistan far predates the 21st century, stretching back decades.

In the weeks and months ahead, there are going to be a lot of questions about what’s next for Afghanistan, including how the US approaches it. But contemplating what happens going forward also means looking at the past, including the ways American involvement has shaped Afghan politics and life for more than 50 years.

During the Cold War, both the US and the Soviet Union sought to gain footholds in Afghanistan, first through infrastructure investments and then military intervention. Once they withdrew in the late 1980s, the country entered a civil war — a backdrop to the rise of the Taliban. And while the US took a back seat in Afghanistan during much of the ’90s, it invaded after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 and undertook a two-decade project for which the underlying mission would evolve. Now President Joe Biden has finally pulled American troops out of Afghanistan, but the two nations are still intertwined.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795014/GettyImages_92981480_copy.jpg) Romano Cagnoni/Getty Images

Romano Cagnoni/Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795133/GettyImages_1229924205_copy.jpg) Rob Curtis/AFP via Getty Images

Rob Curtis/AFP via Getty ImagesI recently spoke with Ali A. Olomi, a historian of the Middle East and Islam at Penn State Abington, about the long, storied history of US meddling in Afghanistan and how it has shaped the country and people’s lives there. Olomi, who is the host of the podcast Head on History, discussed the US’s funding of some factions of the mujahedeen, or Afghan guerrilla fighters, during the 1970s and ’80s; America’s rolling reasoning for its involvement in Afghanistan post-2001; and whether the US, even without soldiers present, is really gone.

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

A lot of people date US intervention in Afghanistan to 2001. But is that the right place to start?

The actuality is that the United States was involved all the way back in the 1950s. Afghanistan was going through a series of modernizing projects, and it attempted to really build into a modern nation-state under two subsequent leaders: first, King Zahir Shah, and then followed by his cousin who overthrew him, President Mohammad Daoud Khan. And it was right in the midst of the Cold War.

Both the Soviet Union and the United States were involved in Afghanistan, namely through infrastructure building. The Soviet Union really built what’s known as the Salang Tunnel, which connected northern Afghanistan to Kabul. The United States was involved in what was known as the Helmand Valley project, which was an irrigation project and agricultural project about building dams in southern Afghanistan. It had been funneling a significant amount of money from the ’50s and ’60s on.

There was a lot of money coming from both of these big, great powers in Afghanistan. And that really sets the stage for what eventually becomes a more formal military relationship to the country.

And where does the military relationship start? The 1970s?

Yes. In the ’70s, the United States is at first quite hesitant to support any type of military expansion.

Daoud Khan starts to ally himself more and more with the Soviet Union. He tries to establish a friendly relationship. He has a very famous phrase that he uses: “I feel happiest when I light my American cigarette with Soviet matches.” That really speaks to his attempt to leverage his really weird, uncomfortable Cold War relationship. But his allying with the Soviet Union makes the United States very, very nervous.

Things get even worse in 1978, when Daoud Khan is formally overthrown in what’s known as the Saur Revolution and a Marxist-Leninist government is established, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. Here, the United States starts to slowly funnel money toward some resistance groups. It doesn’t have a unified policy. It’s not like, okay, we need to start a resistance movement to overthrow this communist government. It has a little bit of a muddled approach.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795147/AP551216093.jpg) AP

APThere were some in the [US] government, like former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, who was very interested in getting involved. There were other military leaders that thought if we get involved, that’s going to force the Soviet Union to get involved. And so they have a bit of a mixed bag approach. But they do start to agitate quite early on in 1978, and in 1979, they are funneling money to Pakistan’s intelligence services, who are then funneling it into the hands of the resistance. That does eventually induce a Soviet invasion.

The US was actually involved a little before the Soviets invaded. Once they got invaded, then the United States throws its full backing. It goes from meddling and funneling and agitating to outright saying, “Okay, we need to support the mujahedeen,” and allying themselves with the anti-communist resistance movement.

In the Cold War, the US backs Afghan reactionaries to fight a Soviet-friendly regime

And just to be clear, what is the mujahedeen?

The mujahedeen is a sort of resistance movement that emerges in response to the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. The People’s Democratic Republic party is wildly, wildly repressive, which as a result produces a good deal of resistance.

Now, we should note that it’s also a really progressive government. This is a government that expands women’s rights, it extends literacy, it builds agricultural reforms in the economy. But at the same time, they’re also disappearing people. There are people who are like, hey, I can finally find a job, and other people who are like, wait a minute, we have health care. But if you spoke up against the government, there were chances that you’d be thrown in jail, arrested, disappeared. As a result of that repressive component, there were pockets of resistance that have been growing.

The mujahedeen are not a single group. We often talk about the mujahedeen as one group, but [they were] actually four different kinds of groups that roughly align as resisting this new oppressive, repressive government.

The first is the more organized. There is the Islamist faction, led by people like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who is trained in the sort of jihadist ideology; he’d like to see an Islamic government. He’s a really regressive, retrograde, reactionary figure. In fact, even before the Soviet invasion, he carried out a series of horrific acid attacks against women.

This is a very unsavory character. And he happens to be one of the more organized groups, allied with the more moderate Ahmad Shah Massoud, who’s not carrying out acid attacks. He’s not regressive. He is much more interested in a sort of egalitarian vision of an Islamic republic, one with representative rather than this kind of autocratic rule. And yet despite these ideological differences, these two people ally themselves or at least align in opposition to communist government.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795193/AP20046463966879__1__copy.jpg) AP

APThere’s also leftists as part of the mujahedeen; Maoists and leftists who have been disaffected by this government, who felt that they weren’t being heard or being repressed. And the mujahedeen is also made up of the Communist Party’s own military commanders, a group of young military commanders who defect from the government.

Then the fourth and final group are just ordinary people — people that just pick up arms and fight and resist. They don’t have an ideology. They don’t have any particular vision of what the government is supposed to look like or what the government is supposed to do. They just realize that, wait a minute, this government is oppressive, or they’re changing things in a way that they’re not happy with, and they resist. This movement is a little slower. Once the Soviets invade, this group of ordinary people will grow dramatically, and this is the bulk of the mujahedeen.

We’re talking about a coalition of groups with different aims, different goals that only align when the Soviets are there. Once the Soviets are gone, this group will turn amongst itself and we will see the civil war of the ’90s.

What was the US’s involvement with those different groups?

The US involvement is uneven. The US isn’t just funding mujahedeen. There’s an oversimplification that happens sometimes in this discourse, partly as a result of the US’s own claims. Brzezinski very proudly pats himself on the back and says, “We created the mujahedeen.” But he says this after the fact. In reality, when we look at the archives, that’s not true. [The US] exploits the mujahedeen. They definitely use the mujahedeen to their advantage. And they do funnel money through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). But that money is mostly going into the hands of the more organized groups of the mujahedeen.

Ordinary people aren’t receiving training from the CIA or Pakistan’s ISI. They’re just ordinary people who have guns in their houses, pick up their guns, and fight. But unfortunately, the more organized groups are those reactionary elements. It’s people like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who is an Islamist who is quite dangerous, who does receive funds, who does receive some form of training.

You even have CIA documents that complain that the Afghans are very hard to train because they operate on a different sense of time, that they won’t organize in the same way that the US military will organize. Anyone who’s familiar with Middle Eastern culture, Central Asian culture, or Indian culture knows that if you go to a wedding that says it starts at 7 pm, it’ll start at 9 pm. There’s a similar experience with the mujahedeen: They tell mujahedeen, hey, we’re going to start at 0800, and they’ll do it on their own time.

But it is to these more reactionary elements that the US allies itself. And, in fact, it makes some really horrific blunders. One of the things that the US ends up doing is that it pressures Egypt to release a group of Islamists that it had arrested. And one of the Islamists that was arrested in Egypt and then is released is Ayman al-Zawahiri, who happens to be the second-in-command of al-Qaeda.

The US inadvertently imports him — and we don’t have the full picture, so it could very easily have been intentional as an attempt to bolster the mujahedeen by bringing in foreign fighters. But they start to bring in what are known as the Arab Afghans, or the Arab mujahedeen, and these are people from Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, these are people from Yemen, people from Saudi Arabia, who then go on to form al-Qaeda.

There is a relationship here in which the US, through funneling money to ISI, Pakistan’s intelligence services, either inadvertently or intentionally ends up funding a group of foreign fighters who ally with the more organized elements of the mujahedeen. The consequence of that will be that once the US and the Soviet Union withdraw their influence, Afghanistan falls into a civil war. And in that civil war, both al-Qaeda will be born and the Taliban.

The unintended consequence of that meddling is chaos. And that chaos will give us al-Qaeda and the Taliban, both of whom have American training manuals, some American funds, and American guns, all that they received funneled through Pakistan’s ISI. And now the CIA says, “Oops. We’ve just allowed these groups to take form because we took our eye off of Afghanistan.”

After the Cold War, a civil war brings the Taliban to power

Once the Soviet Union withdraws, and there’s a civil war in Afghanistan, is the US still present during that time? Like, during the ’90s?

The Soviet Union and the United States both sign an agreement, or at least, they are the guarantors of this agreement known as the Geneva Accords. It’s technically between Afghanistan and Pakistan. But the United States agrees that we will no longer fund the mujahedeen, or at least that one group of the mujahedeen, and the Soviet Union agrees that they will withdraw. The Soviet Union does formally withdraw. It leaves no real support for its former allies, the government. And the United States continues to funnel some money, but it mostly turns away.

The result is that within three years, the government collapses and the civil war emerges between these old and mujahedeen factions, who, again, like I mentioned, are completely different with very different visions. It’s in that moment that the United States is not involved, the Soviet Union’s not involved. In fact, the former Soviet Union ambassador will actually blast the United States and the Soviet Union and say, “We meddled in Afghanistan, and then we stopped paying attention.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795259/GettyImages_635231127_copy.jpg) Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty ImagesIt is hidden in that language of “stopped paying attention” that really speaks to what ends up happening. A power vacuum is created, and into that vacuum will step the civil war. From that civil war will be born the Taliban who emerged as a completely new actor. They’re the second generation that grew up in refugee camps in Pakistan — Afghans were born in refugee camps, raised in refugee camps. They arrived fresh onto the scene. They intervene into this civil war, are able to exploit it, and therefore establish the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996-’97.

And how long were the Taliban in control? Until 2001?

The Taliban exerts its authority through most of Afghanistan, not all of it. Unlike now, where they seem to have extended their control to everywhere other than the Panjshir Valley. In the ’90s, they only controlled from Kandahar to Kabul, both Herat and the North did resist quite a bit.

Herat will eventually fall, but the North — led again by the Panjshir Valley, and Ahmad Shah Massoud and what would eventually become known as the United Front or the Northern Alliance — they will have their own autonomous territory that the Taliban will never conquer. So Afghanistan will kind of be split between the Northern Alliance in the North and the Taliban, who establish the Islamic Emirate. And only a few countries will recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan — Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. But they fall in 2001, relatively quickly.

The US invades after 9/11, without clear goals. The Taliban wait out the long war.

And that’s after the US invades?

The US starts, actually, through a bombing campaign, and the Taliban really collapses there. The Taliban doesn’t have air support, there’s no Taliban air force. And so they actually pursued peace quite early on.

In October 2001, they offer to hand over Osama bin Laden in return for an end to the bombing campaign. The Bush administration, at the time, didn’t accept it, and a formal invasion is undertaken. The offer was rejected because the Taliban wanted to hand him over to a third party and for a trial. The US also viewed their mission as “ending a safe haven for terror,” so invasion was explicitly part of the plans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795278/AP21119536380190.jpg) Mazhar Ali Khan/AP

Mazhar Ali Khan/APThe Taliban just completely vanish and become a small insurgency group that lives mostly in mountains. Some of them try to escape into hiding in Pakistan, some of them end up in pockets in Kandahar, some of them are in safe houses. But they’re no longer a sort of organized, unified group. They’re no longer in government.

They’re just pockets of insurgency allied with al-Qaeda. They won’t really emerge until the mid-2010s, where they are much more organized and seem to have received more money than they ever had. There’s some estimates that we’re looking at billions of dollars. Somehow, in the process, they were defeated, they went away and hid and kind of built a spate of an economic base through extortion and drug trafficking. They were reorganized in the 2010s and emerged as once more a sort of unified political movement.

To back up a bit, and I feel odd asking this, but why did the US even go to Afghanistan in 2001? Because of al-Qaeda? Because of bin Laden? I feel like we all sort of know this and we don’t.

Ostensibly, the reason was, first, some form of justice against Osama bin Laden, some form of revenge, that we need to get him for what he did, for 9/11. But there was also a language of liberation that was woven into it. And that was more of an addition, a post-hoc, after-the-fact justification. The main justification was to go after Osama bin Laden. Once the Taliban collapses, and they say, “Hey, we’ll hand over Osama bin Laden,” a sort of new justification had to be invented. And that was, we need to nation-build, we need to build Afghanistan up.

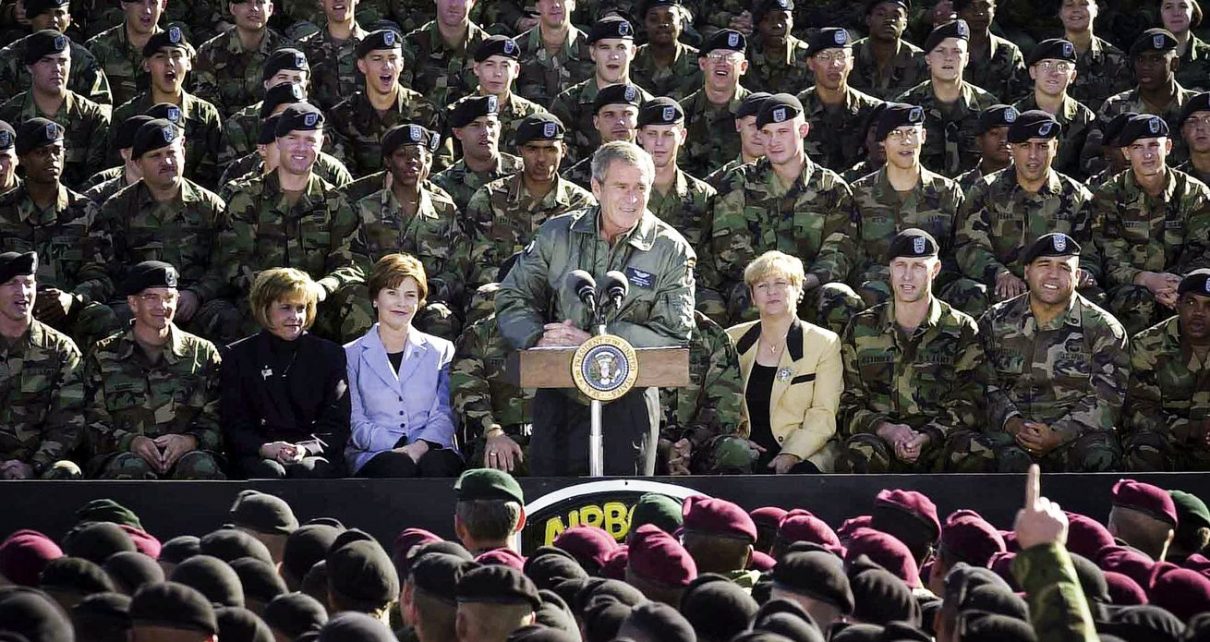

What we can see of the internal discussions between former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and former Vice President Cheney and former President George W. Bush, the argument or justification for why they want to nation-build is, one, so that they can create a pro-American government, a foothold in the region, and therefore are able to extend American bases. And two, so that they can therefore create a nation-state that’s favorable to the United States and would not allow terror bases to ever take root there again.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795271/AP060512013693_copy.jpg) Ron Edmonds/AP

Ron Edmonds/APThe justification was that it was to prevent future attacks, but it was also about extending American military bases and allowing more bases to be built there and therefore extending American military might.

Part of the strength of the American military has always been the ability to deploy quickly. If you have to deploy from the United States, that’s going to take time. This is one of the reasons we have aircraft carriers in various parts of the ocean; it’s why we build the bases in places like Djibouti. And the United States thinks in those terms. So the ability to build bases is a very important aspect of invading Afghanistan — build American bases, make an American-friendly government, or at least allow it to take root there.

Technically, the US could have accepted the surrender, accepted Osama bin Laden, and that’s it. Justice is served, right? Put Osama bin Laden on trial or execute him or whatever. But going further by invading was an attempt to extend American influence in that region.

That’s where the United States got involved in, I think, a bit of a quagmire, because not only did it not know how to build the infrastructure, or the democratic institutions, but more importantly, it flooded Afghanistan with money that often went into the hands of military contractors and advisers and all these different segments — even warlords — who all got really rich off of American dollars.

Afghan society never really got any of those benefits. The economic disparity was still real. There was no real social mobility; jobs were incredibly hard to come by. So, yeah, you develop Kabul with new skyscrapers, and maybe you have a couple KFCs there, but the rural parts of Afghanistan remain neglected. And that, in many ways, is the great failure of the United States’ invasion.

A failed rebuilding, and the US withdraws once more. But is this the end?

How has the United States’ involvement in Afghanistan shaped life for the people there?

I think that in one instance, it did offer an opportunity to think of the future in a different way. There was a sense of hopelessness with the Taliban. I think post-2001, there is a great sense of energy and excitement and opportunity that does open up when we’re talking about people who are thinking about becoming engineers or journalists or going into government. So there is a great activity of optimism and an attempt to really reform society.

Also, it is coupled with a very real contradiction of that, that the United States was a major aggressor still. The United States wasn’t just in Afghanistan, it was carrying out a droning campaign. And so young Afghans would grow up with the experience of, okay, I can go to school today, something I may not have been able to do under the Taliban. But that also means that if the skies are blue, I might get droned.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795285/GettyImages_1233700582_copy.jpg) Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times via Getty ImagesSo they had to live in this really precarious, frustrated environment where, yes, there was some really great progress, some really great strides, things opening up. But simultaneously, they were recognizing and acknowledging the fact that the US was still at war, carrying out bombing campaigns. The government that was set up was precarious, at best, corrupt at worst. And so there was a real complicated feeling.

I speak to Afghans, I have family there, and they’ll tell you that there’s a lot of great and beautiful things, jobs and opportunities. But there’s also the real sense that an American tank is just going to roll down your street, that if you, unfortunately, move in a certain way, nervous troops are going to fire on you because they think you have a bomb, they think that you are part of al-Qaeda.

That anxiety was real. Afghans felt occupied, while simultaneously also seeing that there were these different changes in society, that there was a transformation taking place. And that tension was very real for them — the experience of occupation and the experience of change and transformation.

How do you describe the situation now? I mean, I don’t know how to describe the situation now.

Nobody does; you’re not alone. Experts don’t know how to describe this situation. It’s a bizarre moment. We don’t know what the formal policy toward Afghanistan will be. There is obviously a military withdrawal, but will the United States normalize the relationship with the Taliban? Will the former enemies suddenly become a government?

We know that they’re thinking of blocking the money, so there’s that element of it. But what happens if most of the countries in the world recognize the Taliban as the rightful leaders of Afghanistan, even if Afghans themselves don’t? The majority of Afghans despise the Taliban; they’re universally hated across ethnic groups and political spectrums. But what happens with the de facto relationship that’s going to be? The United States allied itself with all sorts of unsavory governments — Saudi Arabia, right? What is that relationship going to be? Nobody knows.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795340/AP21231364890781_copy.jpg) Rahmat Gul/AP

Rahmat Gul/AP/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22795355/GettyImages_1234761729_copy.jpg) Shakib Rahmani/AFP via Getty Images

Shakib Rahmani/AFP via Getty ImagesIt seems that the military engagement, at least in terms of troops, is going to end, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that droning is going to end. So the Afghan experience of death from above is going to continue. In fact, President Joe Biden made it very openly clear that he will continue to use America’s Air Force to “degrade the terrorists,” which is a code for drone warfare. The continuation of drones in Afghanistan means that while US troops might be gone, US presence might be gone, the threat of US military is still there.

We also don’t know what the US’s commitments are to ordinary Afghans. Will they now be willing to take more refugees? The answer is yes, so far, but there’s no real talk about really raising the cap of dealing with things like the visa process, which is a complete quagmire, a labyrinthine process that is impossible to navigate. An Afghan who’s been cut off from the internet, how are they supposed to navigate that process?

There are no answers, just questions that have been raised by what is going on. There’s also the real anxiety that Afghanistan may fall into an outright civil war within a matter of years. What happens there? Do we stand by and watch a humanitarian crisis unfold? I think the universal feeling among most Afghans — and I should be careful not to speak for every Afghan — but there is a sort of acceptance that US withdrawal is a good thing. But what is the US going to do after is a crucial question that needs to be answered. And it is not being answered yet.