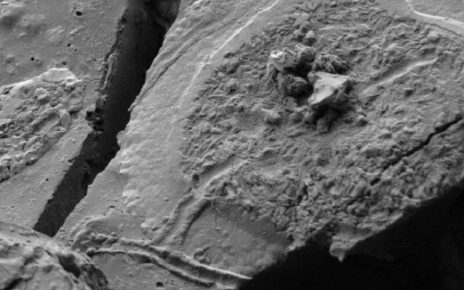

(credit: Leder et al. 2021)

During the Middle Ages, people ventured into the cave now called Einhornhohle to collect unicorn bones. It’s tempting to wonder whether those medieval cryptid hunters would be disappointed or fascinated to learn that the bones they unearthed from the cave actually belonged to ancient bison, deer, cave lions, bears, and other animals that died 50,000 years ago. Archaeologists began excavating the cave in 2017, and while cleaning and sorting their trove of non-unicorn bones, they discovered the handiwork of a long-dead Neanderthal artisan.

Around 51,000 years ago, someone carved a geometric design into the second phalanx, or toe bone, of a giant deer. The carver was almost certainly a Neanderthal, based on the bone’s radiocarbon-dated age, because no one but Neanderthals lived in Europe until around 45,000 years ago. As archaeologist Dirk Leder of the Lower Saxony State Service for Cultural Heritage and his colleagues put it, Einhornhohle is “situated along the northern boundary of the world known to be inhabited by Neanderthals,” in the Harz Mountains of northern Germany.

Three parallel lines cut diagonally across the surface of the bone. Another of set of parallel lines cross the first three at more-or-less a right angle; the carver was a few degrees off, but that’s still respectably precise for someone eyeballing their measurements and working with a flint blade. At the base of the bone (the end closer to the leg), the carver added four short lines, roughly parallel but not lined up quite as precisely as the others. Leder and his colleagues describe the resulting pattern as “offset chevrons.”