One year on, the first national security trial shows how.

Tong Ying-kit was arrested a year ago, accused of driving a motorcycle into a group of policemen, a flag trailing behind him that read: “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times.”

His trial, which began last week, marks a milestone for Hong Kong: Tong is the first person charged under its national security law.

The Beijing-imposed legislation went into effect a year ago. It is vague, it is broad, and it targets crimes such as secession, subversion, colluding with foreign powers, and terrorism. It portended a sweeping crackdown on dissent and an erosion of the rule of law in Hong Kong. Since then, more than 100 people have been arrested under the national security law, and more than 50 charged. And now, with Tong’s trial underway, the crackdown is here.

Tong’s saga reveals how deeply the national security law has transformed Hong Kong in just one year. It has chilled Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. But it has also radically — and swiftly — disrupted the territory’s long tradition of an independent judiciary.

As this trial plays out, it will set a precedent for the national security defendants who come after. Tong’s trial is the first, but it will not be an outlier.

“It is the application of a law,” said Martin Flaherty, a professor of international law at Fordham University School of Law, “that means the end of Hong Kong as the world knew it.”

Tong Ying-kit’s trial and the national security law

On July 1, 1997, Great Britain returned Hong Kong to China’s control. The handover created a setup known as “one country, two systems,” which established that Hong Kong would maintain separate economic and political systems from mainland China for 50 years, through at least 2047. That includes Hong Kong’s storied tradition of common law, an independent judiciary, and protections for certain freedoms like speech, assembly, and the press, which are preserved in Hong Kong’s Basic Law, a kind of mini-constitution.

The date of the handover has traditionally been one of protest in Hong Kong among those who oppose China’s rule — and, in the years since 1997, Beijing’s tightening of control over the territory. That included in 2019, when a summer of massive protests against the Hong Kong government over a controversial extradition bill grew into a larger pro-democracy movement. The Chinese government started to lose patience with the months of unrest, and after the coronavirus pandemic slowed protests in 2020, China interceded with its national security law to crush the resistance for good.

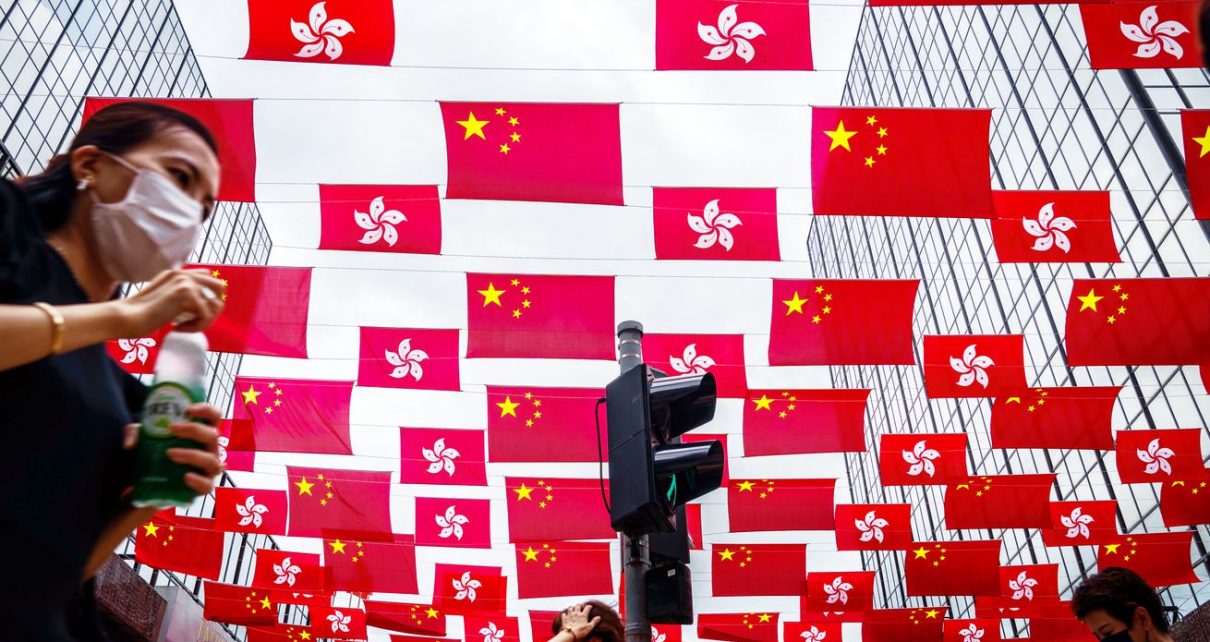

On July 1, 2020, Hongkongers still demonstrated, in defiance of both coronavirus restrictions and the new national security law. Quickly, though, national security arrests began, including of people who had signs and flags calling for Hong Kong’s independence.

Tong Ying-kit was among them. Reportedly a 24-year-old cook at a ramen restaurant, Tong faces two counts under the national security law: terrorism and inciting secession. The charge of inciting secession is tied to the “Liberate Hong Kong” flag he brandished, which authorities say represents pro-independence sentiments. That slogan has been a feature of Hong Kong resistance for years, but is effectively banned under the national security law.

The terrorism charges are a bit weird, and are apparently tied to police claiming he tried to run them over with his motorcycle. Tong’s lawyers are arguing he did not intentionally hit the police, but lost control of his bike after being distracted when a police officer swung his shield toward him. Prosecutors have tried to say that Tong rode through police cordons, and then attempted to run over three officers who tried to stop him.

Recently, prosecutors added a dangerous driving charge under previously existing traffic laws, a non-national-security-law offense. Experts said this type of criminal charge would have been far more likely before the national security law, or perhaps might have been coupled with other criminal offenses, such as assault.

Tong has pleaded not guilty to the charges. The full outcome of the trial is still unclear, though Tong is unlikely to escape consequence-free.

But even before the verdict, Tong’s case reveals how profoundly Hong Kong’s judiciary is straining under the national security law, as it shreds the typical protections and rights afforded defendants.

The new national security law threatens Hong Kong’s judicial system

Two elements make Tong’s case so troubling: first, his denial of bail, and second, his denial of a trial by jury.

Tong wasn’t alone in being denied bail — dozens and dozens of other defendants charged under the law have been held in custody for months. Typically, defendants have a right to request bail unless prosecutors have a legitimate reason to retain the accused in custody.

But the national security law sets a convoluted bail standard, experts said. The burden is on the defendant to show that they will not continue to engage in any activity that will endanger national security.

This is a tough bar to meet, first because what constitutes endangering national security is very broad — subversion or “colluding with foreign powers” are basically whatever authorities want them to be. And second, because, in many cases, defendants say they didn’t engage in actions that endangered national security in the first place. As Flaherty put it, this creates the ultimate catch-22.

This makes it safe to say, said Lydia Wong, a research fellow at the Center for Asian Law at the Georgetown University Law Center, that bail for national security defendants is “basically nonexistent.”

Perhaps the most chilling element of Tong’s case is the denial of a trial by jury. Experts told me that a trial by jury is a cornerstone of Hong Kong’s common law, and is enshrined in its Basic Law. A trial without one — especially one where the defendant potentially faces life imprisonment — is unprecedented.

A provision of the national security law allows juries to be scrapped in certain cases, and the law includes a vaguely defined concern for jurors’ safety as justification for doing so. Hong Kong’s High Court ruled earlier this year that convening a jury in Tong’s case could potentially put “jurors and their family members at risk.” Tong’s lawyers appealed the ruling, but the ruling stood. Instead, a three-judge panel will hear Tong’s case.

That panel isn’t made up of any three judges, either. These justices are designated to specifically handle national security cases. They are selected by Chief Executive Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief administrator who also happens to be handpicked by Beijing.

Together, it looks like a very deliberate effort to limit scrutiny in these national security trials, carving out a kind of parallel justice system. “The government really wants to diminish transparency for national security crimes in as many ways as they can — I will not say to control the outcome, but limit the choices of the outcome,” said Eric Lai, a Hong Kong law fellow at the Center for Asian Law at Georgetown.

A free and fair jury trial would inject uncertainty into the trial result. That is not really the outcome the Chinese government wants, as the point of introducing such a draconian law is to use it — to punish those who dissent, and make the stakes so high it deters the rest. The lack of public input could empower the prosecution, or judges, to act without any accountability, essentially creating a sham court system that starts looking a lot more like China’s.

A jury-less trial is just one way to achieve that. The national security law also allows for defendants to be tried on the mainland, crumbling entirely any semblance of two separate legal systems. As some experts ruefully pointed out, Tong is lucky, at least, to have Hong Kong judges presiding over his case, as China doesn’t even have a tradition of an independent judiciary to undermine in the first place.

Taken together, the national security law represents the “mainlandization” of Hong Kong’s judicial system, said Fiona de Londras, chair of global legal studies at Birmingham Law School.

The fundamental principles of the common law and legal autonomy of Hong Kong aren’t being chipped away at. “They’re being bludgeoned,” de Londras said.

The “one country, two systems” policy is over, and then some

Tong isn’t a high-profile pro-democracy figure, someone who’s long been a leader of the movement, or an outspoken media mogul. Little is known about him. The more violent allegations — that he barreled into officers — make his case a little more complicated than the most extreme applications of the national security law, like charging lawmakers who participated in election primaries with attempting to overthrow the government.

Lai, of Georgetown, said that may be the point. Tong’s case is a “way to test the water, to test how these new measures under the new national security law work — without a strong backfire from the global community.”

That shouldn’t obscure the very real unraveling that Tong’s case represents. More people will be denied bail; many more will be denied jury trials. Experts said they see other areas where Beijing’s influence and pressure is knocking off, one by one, the kind of institutions that make the rule of law possible.

For one, experts said they are concerned about the larger independence of Hong Kong’s judiciary, as judges who have appear to have ruled in favor of pro-democracy figures in non-national-security-law cases often come under attack from the pro-Beijing media.

There are also growing concerns about defendants’ right to counsel, and whether those charged can select their legal representation. A national security case involving Hong Kong activist Andy Li raised questions as to who had appointed his attorney. The fear is that prosecutors themselves are perhaps appointing defense attorneys, an obvious conflict of interest and another way to limit the outcomes in any national security trial.

All of this is commonplace in China’s legal system — which, again, is the point. Hong Kong’s rule of law was one of the last bastions of the “two systems.” The national security law is deliberately tearing that away. A senior Chinese official, Zheng Yanxiong, who’s in charge of overseeing the national security law, said, according to the Guardian, that Hong Kong’s rule of law was a “source of [its] charm,” but ultimately, the real goal of the judiciary was to “highly manifest the national will and national interest.”

The imposition of China’s will is not limited to the judicial system. The shutdown of Apple Daily, and the arrest of its journalists, is destroying freedom of the press. The targeting of academics and university professors is dismantling freedom of expression. The silencing of the annual Tiananmen Square vigil — the only memorial in greater China — is an attempt to erase dissent.

“Beijing [is] determined to reshape Hong Kong by this unprecedented law,” Lai said.

Tong’s trial is just another component of this effort. It shows China will apply and enforce the national security law to impose its will on the territory. It is designed to punish anyone who advocates for democracy, and acts as a warning to anyone else who might try to do so.

And the national security law serves one more goal — maybe the most important one of all — de Londras, of Birmingham Law, said. It makes “it very clear to the people who live in Hong Kong, who is in charge of this territory. And it is not them.”