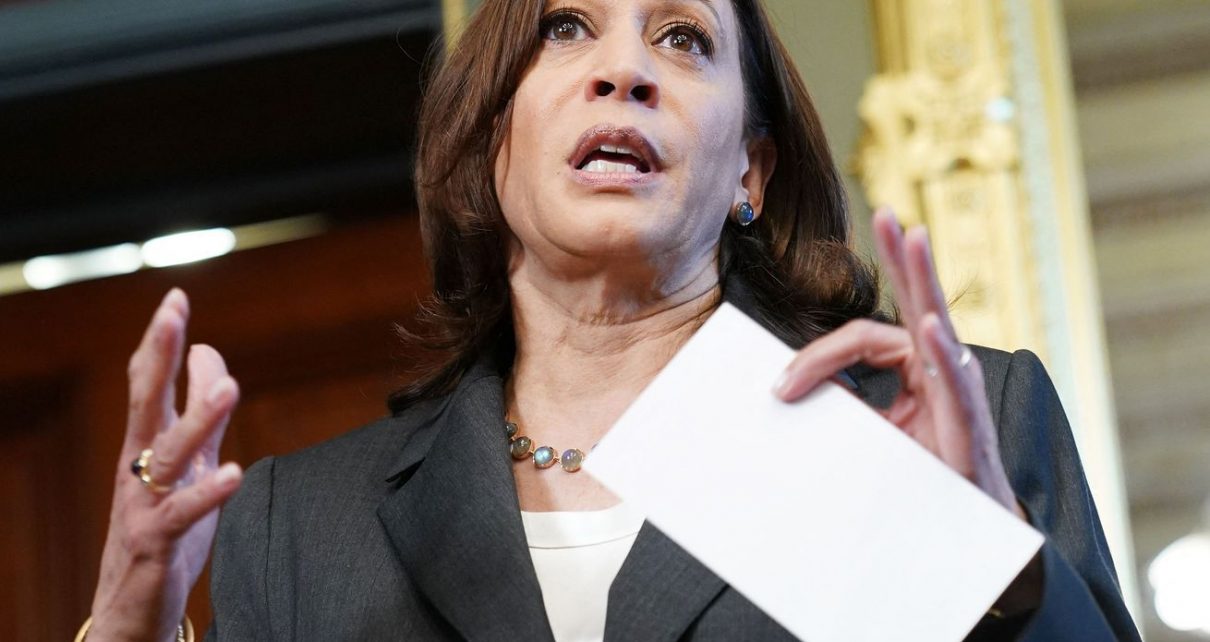

Kamala Harris wants big US companies to invest in Central America.

A key prong of the Biden administration’s plan to address the root causes of migration from Central America is to bring more foreign investment to the region, to improve economic opportunities and give people a reason to stay.

Vice President Kamala Harris recently announced a partnership with 12 private-sector companies and organizations to support “inclusive economic development” in the Northern Triangle of Central America, which includes Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. US government agencies, including the State Department, will also work with governments in the region to remove impediments to international investment and foster new private-sector partnerships.

Among the commitments, Mastercard is supporting 1 million small businesses in the region; Chobani is creating a startup incubator for food entrepreneurs in Guatemala; Microsoft is expanding broadband access to up to 3 million people by next July; and Nespresso is starting to source coffee from El Salvador and Honduras and expanding its existing operations in Guatemala with a minimum $150 million investment by 2025.

Though the lack of foreign investment is far from the only factor driving people to make the journey north, the idea is that improving economic conditions will contribute to overall stability in the region, which has long suffered from persistent corruption, weak government institutions, and high levels of violent crime.

“The benefit of this effort will probably not evidence itself overnight, but will be well worth it,” Harris said of the initiative. “We do understand our work is in the context of long-standing and deep-rooted factors.”

But experts say there’s a long way to go in persuading would-be migrants that the economic opportunities at home are better than what they might find in the US.

“The amount of money that needs to be going into these countries to really begin to make a dent in matters of employment — in allowing people to make salaries to fulfill their basic needs — is far bigger than we have seen in any recent time,” said Oscar Chacon, executive director of Alianza Americas, a network of Latin American and Caribbean immigrant organizations in the United States.

Currently, an average of about 76 percent of workers among the three Northern Triangle countries have informal, often low-paying jobs — as street vendors, domestic workers, farm workers, and in service industries — without a fixed monthly salary or benefits. They typically do not pay taxes, meaning that they cannot access government pensions or credit from financial institutions, and are often working in poor conditions with little job security or assurance that they can meet their families’ basic needs.

What’s more, direct foreign investment in the region has been minimal in recent decades. In 2019, the last year for which there is available data, foreign investment to El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala was just under $2.2 billion combined, according to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. By comparison, migrants who left those countries sent a total of $22 billion in remittances back home that year.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22663376/EoQz9_weak_foreign_investment_in_the_northern_triangle.png) Nicole Narea/Vox

Nicole Narea/Vox That suggests that the levels of foreign investment required to change the calculus around people’s decisions to migrate is much larger than what the region has received in the past. Harris’s initiative, therefore, only represents a starting point.

And experts say it should be coupled with other measures to improve the quality of life in the Northern Triangle and not come at the expense of partnerships with local organizations that might have a better sense of how to effectively put US dollars to use than large, multinational companies.

The US needs to help Northern Triangle countries prepare their workforce for better opportunities

Harris’s public-private partnership recognizes that immediately putting money in people’s pockets is the first step toward meaningfully improving quality of life in the Northern Triangle.

For immigrant advocates and civil society groups working in the region, that understanding is a welcome shift from former President Donald Trump’s decision to slash US aid to the region by a third, as well as from the security-focused agenda of the Obama administration, which tied US aid to governments’ ability to crack down on crime and reduce homicide rates.

But there’s a question of what happens if that money stops flowing in the long term — say, if the midterm elections in the US bring about changes in congressional leadership, or if there is a change in administration in 2024.

A potentially more enduring solution is ensuring that the Northern Triangle’s workforce is prepared to attract more foreign investment and compete for higher-quality jobs in a global market. That can also help alleviate the structural inequality in these economies, which are dominated by elites, many of whom bribe politicians to enable their illicit and anticompetitive business practices.

But such a transformation of the workforce might take well over a decade to achieve.

“In order for Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala to really compete for good jobs, there is a bit of a homework that needs to be done in terms of preparing the actual workforce in these countries to be in a position to assimilate the possibility of a Microsoft or Google or any other technology company that wants to do heavy investments in these countries,” Chacon said.

That means improving education — and not just formal education, but also vocational training that can set up students to fill niches sought out by international investors.

“We still don’t have a level of education such that we can manufacture or assemble cars or computers,” said Lester Ramirez, the director of governance and transparency at the Association for a More Just Society, a civil society group based in Honduras. “That is something that we should be working on, if we want to be part of the global market.“

It also involves more basic quality-of-life improvements, such as ensuring that workers are healthy and have access to medical care, and that there is rule of law.

Costa Rica, which brought in $2.5 billion in direct foreign investment in 2019 — more than all of the Northern Triangle countries combined — can serve as a potential model in that respect. Unlike the Northern Triangle, it has invested in preparing a qualified workforce to be competitive, and not just for low-paying jobs, Chacon said.

“Investors in Costa Rica are very confident that the rules are there solidly in place, that they have a very good system of checks and balances, and that there is hardly any corruption anybody can point to,” he said. “That is very different from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.”

US companies can help curb corruption — so long as they don’t exploit workers

There are pros and cons to bringing in big, multinational companies to invest in the Northern Triangle.

They can help bring more people into the formal economy and will pay taxes, which can help support a social safety net that governments in the region have so far been unable to provide.

That’s important because countries in the Northern Triangle have among the lowest effective tax rates in the world. Workers with informal jobs don’t typically pay taxes and local corporations often try to evade them, which has hampered governments’ ability to provide social services.

Guatemala’s 2019 tax revenue, for instance, was just 13.1 percent of its GDP — the lowest among Latin America and Caribbean countries, which by comparison brought in nearly 23 percent of their GDP on average.

“The private sector in Central America has demonstrated decade after decade that it really is unwilling to pay higher taxes to reinvest in the human capital of the people of Central America,” said Paul Angelo, a fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

While US companies might also try to get out of paying their fair share of taxes, they are still better than their Central American counterparts in that respect.

What’s more, American companies can serve as a more reliable partner for the Biden administration than government actors in the region who have perpetuated the problems that are driving people to flee.

Juan Orlando Hernández, the president of Honduras, has been named as a co-conspirator in his brother’s drug crimes by US prosecutors and remains under investigation by the Department of Justice. Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, has earned a reputation as a “millennial dictator” for strong-arm tactics such as sending troops to pressure lawmakers to approve anti-crime funding and ousting his critics in the country’s Supreme Court and attorney general’s office.

“In the Northern Triangle countries, we don’t really have any democratically-minded or reform-minded [government] partners,” Angelo said. “And so I think it’s only natural that the US government would seek to partner with the private sector, and particularly with American companies that we know generally abide by the rule of law.”

But the influence of US corporations in the region hasn’t been all positive in the past. They have engaged in their own kind of exploitative business practices: for example, preventing workplaces from unionizing by simply taking their business to another country in the region to assure themselves cheap labor, Chacon said.

He added that the US government has historically ignored these practices and allowed American companies to perpetuate “voracious capitalism.” The Biden administration can’t allow international companies to repeat those mistakes. Just as the Biden administration is turning attention to worker rights in the US, it should do the same in Central America, Chacon said.

And some say the administration should focus its efforts primarily on coordinating with local civil society groups, who better understand the challenges on the ground than any large multinational corporation or organization or even US government agency. Harris has prioritized meeting with such groups early on — particularly in Guatemala, which has the most developed civil society of the three countries — but advocates from the region want to see even more collaboration.

Civil society groups in the Northern Triangle are “much more committed to see that the projects are successful,” Chacon said. “The US would do much better by not only investing more, but investing in a truly new set of partners, both in the rural areas as well as in the cities.”