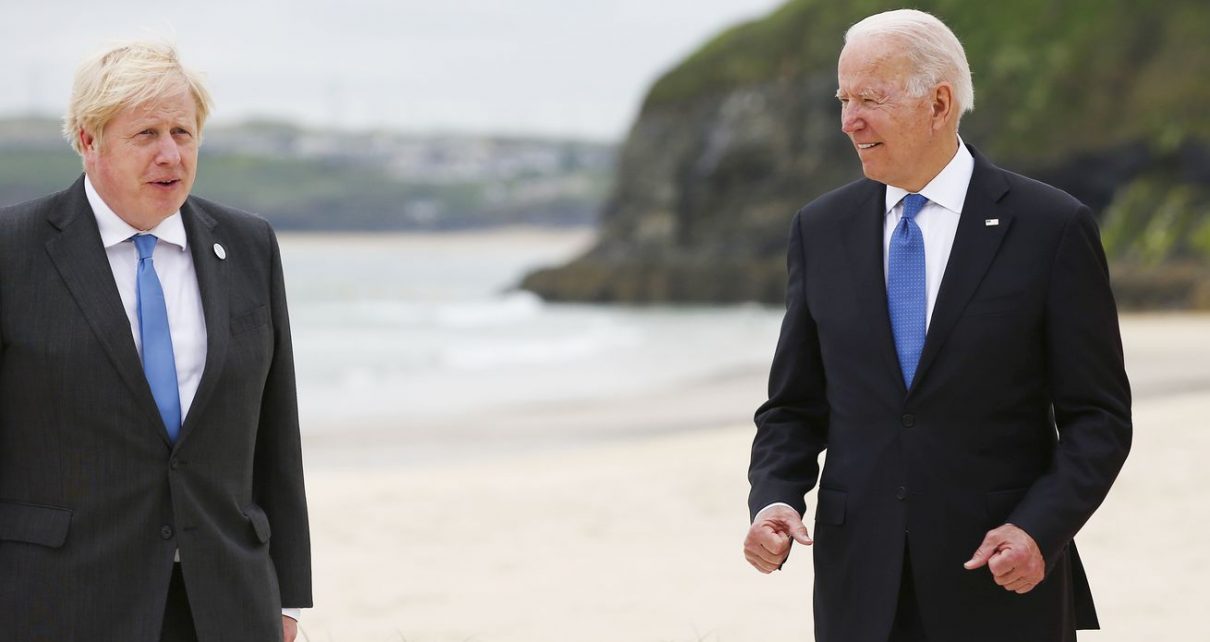

Can Joe Biden do anything about the Brexit fallout?

President Joe Biden had two goals for his trip to Europe: reassure allies that America is engaged again, and rally like-minded democracies to stand together against authoritarians such as China.

But that unity is being complicated by an increasingly tense rift between the United Kingdom and the European Union over Brexit trade arrangements in Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland factored heavily into the Brexit negotiations, as maintaining an open border on the island of Ireland was critical to preserving a more than 20-year peace process. The UK and EU came to a compromise plan, but the implementation has faced significant hurdles, and the fallout is inflaming tensions among some communities in Northern Ireland.

The future of Northern Ireland is important to Biden both politically and personally, and he’s far from the only US politician who feels the same. But the deepening distrust between the UK and the EU also poses a threat to Biden’s broader foreign policy agenda.

Which is why the US president could become a player in one of the thorniest issues in all of Brexit. Whether he’s able to ease the standoff will be a test of Biden’s diplomacy, and US influence on the continent post-Trump.

The EU-UK spat is about a really sensitive border. Also, sausages.

Before we get to what Biden is doing, it’s probably helpful to explain what is going on.

Brexit happened, and the United Kingdom formally left the European Union. But the UK and EU are still arguing over the deal they both signed on the status of Northern Ireland.

When the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union in 2016, it created the tricky issue of what to do about the land border between Northern Ireland (which is part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (which is an independent country and part of the EU).

It is no ordinary border. During the decades of bloody sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles, that border was heavily militarized, and it served as both a symbol of the strife and a very real target for nationalist paramilitary groups.

A critical part of the Good Friday Agreement, the 1998 peace process that ended the Troubles, involved increasing cooperation between Northern Ireland and Ireland. That meant softening the border between the two. As a result, the 310-mile border is practically invisible and completely free from checks and physical infrastructure today.

But once the UK and EU split up, that would become the only land border between the UK and Europe. And with the two sides following different trade rules (that was one of the main points of Brexit), there would need to be some kind of checks put back in place to regulate the goods crossing the border.

So you see the problem: Not having any checkpoints or physical border is seen as critical to maintaining the peace. But the UK’s departure from the EU (and its trading rules) made some sort of customs check necessary.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22663683/GettyImages_1232407768_copy.jpg) Charles McQuillan/Getty Images

Charles McQuillan/Getty ImagesThe UK and the EU ultimately coalesced around a plan that carved out a special status for Northern Ireland. It would leave with the UK but follow many of the EU’s rules, thus keeping that land border open. To achieve this, certain goods coming into Northern Ireland from the rest of Great Britain would require checks, just in case they ended up in the EU’s single market. This put a customs border in the Irish Sea — effectively, within the UK.

Once the Brexit transition period ended at the start of 2021, that Northern Ireland protocol started to become a reality — and, with it, new trade frictions that hadn’t existed before. That was even before all the terms of the deal were implemented, as the protocol provided grace periods for certain rules.

In March, a set of grace periods expired for some provisions, and at the time, the UK just unilaterally extended those deadlines. The EU reminded the UK that, this being a treaty and all, the UK couldn’t just act alone, and so sued them for breaking international law.

Now another set of grace periods is expiring at the end of the month, including a provision related to chilled meats, such as sausages. The UK now needs to start conducting regulatory checks on any chilled meats coming into Northern Ireland from the rest of Great Britain. If the UK doesn’t do them, it would effectively prevent Great Britain from selling its own sausages in Northern Ireland, since those, in theory, might be at risk of entering Ireland, which could mean illicit sausages in the EU single market.

The sausage dilemma is really just the latest fracture between the EU and UK. The EU thinks Boris Johnson’s government isn’t an honest broker and is likely to renege on the protocol once again.

“It’s not about sausages per se, it really is about the fact that an agreement had been entered into, not too long ago,” Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Micheál Martin said. “If there’s consistent, unilateral deviation from that agreement, that clearly undermines the broader relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom, which is in nobody’s interest.”

Johnson, meanwhile, says he’s defending the territorial and economic integrity of the UK. His government has accused the EU of failing to do anything to minimize the trade frictions, which may leave them no choice but to get rid of the deal entirely. The problem, of course, is that Johnson himself signed up to the rules that he no longer seems to like very much.

The concern now is that Johnson will once again just suspend parts of the deal, and the EU will retaliate — potentially with tariffs, increasing the likelihood of a trade spat and decreasing the chances of any real, meaningful compromise on the Northern Ireland trade protocol.

If this were just a minor trade disagreement about chilled meats, that would be one thing. But the protocol has revived tensions in Northern Ireland itself, specifically among the unionist community in Northern Ireland.

The unionists reject any division between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK (i.e., they support the union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland), and some feel, not totally incorrectly, that they were shunted aside in the Brexit deal. Some unionists are urging the UK to scrap the deal entirely. Northern Ireland saw unrest back in the spring, and there are fears over renewed violence, especially as “marching season” reaches its peak on July 12, when loyalists — extreme unionists — engage in parades and demonstrations.

If violence does break out, this could set back the peace process, whose imperfections Brexit has exposed. This is why the Biden administration repeatedly invokes the Good Friday Agreement, and brought it up ahead of, and during, Biden’s trip to Europe.

Biden was always going to matter in the Brexit aftermath

Biden was always going to be a potential force in the post-Brexit EU-UK fallout, and, as in many things, he’s quite the contrast to former President Donald Trump.

Trump liked the idea of Brexit and was eager to strike a free trade deal with the United Kingdom, something Johnson and Brexiteers sold as a big prize when the UK left the EU.

Biden, never a fan of Brexit, made one thing very clear both as a candidate and as president: that the UK’s exit from the EU must not undermine the Good Friday Agreement, which diplomatic efforts by the Clinton administration helped shape.

Biden also has a much deeper interest in the status of Northern Ireland for both political and personal reasons. He was among a group of senators pushing for US engagement on the issue since the 1980s, and he was the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the Clinton administration’s efforts to build a peace deal in Northern Ireland.

Biden, like many other bipartisan lawmakers, sees the US’s role in the peace process as a major foreign policy achievement, and he wants to preserve that. Also, in case you haven’t heard, Biden is of Irish heritage, which has profoundly shaped his identity.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22663676/GettyImages_1233397696_copy.jpg) Jack Hill/Getty Images

Jack Hill/Getty ImagesA trade deal with the United Kingdom also just isn’t as big a priority for the Biden administration as it was for Trump, and both Biden and many powerful Democrats in Congress have said any US-UK deal should be contingent on the protection of the Good Friday Agreement.

All of this meant Biden was expected to be more proactive on the Northern Ireland issue. And the president’s first foreign trip just happened to coincide with the increased tensions in the EU and the UK over Northern Ireland, meaning the US president’s position mattered more than ever — and, in some ways, the implications of the EU and the UK’s bickering stood out even more.

How Biden has flexed his diplomacy on Northern Ireland so far

Biden has stepped up the pressure, particularly on London, to resolve the sausage wars.

Ahead of his trip, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan advertised that Biden would bring up the issue with Johnson. “Any steps that imperil or undermine [the Good Friday Agreement] will not be welcomed by the United States,” Sullivan told reporters last week.

The United States made a few other moves as Biden headed overseas. The first involved reassurances the Biden administration reportedly gave to the Johnson government over a possible US-UK trade deal, saying that if the UK agreed to follow EU veterinary and food standards temporarily, it wouldn’t jeopardize a possible free trade agreement with the US.

This seemingly benign statement about food standards is actually kind of a big deal: The US usually tries to advance its own agriculture sector in trade deals, and the US has different food standards than either the UK or the EU. (You may recall the “chlorinated chicken” debate around US-UK trade talks.)

But this statement is the US basically telling the UK, “Don’t worry about us — getting yourself in order with the EU is the main thing.” And truly, if the EU and UK don’t diverge on standards on animals, food, and plants, it could eliminate a vast majority of the checks on goods coming from the rest of the UK to Northern Ireland.

As Roger Mac Ginty, professor of defense, development, and diplomacy at Durham University, wrote in an email, the US-UK trade deal is the biggest point of leverage for the US administration. One of the reasons the UK had bristled at EU standards was over trade deals, including with the US. So this little nudge matters.

The Biden administration also reportedly offered a more direct admonishment of the Johnson government. Before Biden’s trip, the British newspaper The Times reported that the top US diplomat in London sent what’s known as a demarche, a diplomatic cable that’s basically a formal rebuke, to chief Brexit negotiator David Frost, saying the UK was “inflaming” tensions.

The White House denied that it sent the formal reprimand, but the leak itself seemed to show that the US wasn’t messing around. “That’s not low-key diplomacy, that’s a big slap on the wrist, and the US doesn’t usually do that to the UK,” said Liam Kennedy, a professor of American Studies at the Clinton Institute at the University College Dublin.

The issue of Northern Ireland also loomed over Biden’s in-person meeting with Johnson. Biden broached the subject with him and pushed for the two sides to work out their differences. Sullivan, the national security adviser, told reporters the two leaders had a “candid” discussion but wouldn’t go into details. Johnson told reporters Biden didn’t pressure him on the issue (and called Biden a “breath of fresh air”), but the Good Friday Agreement featured heavily in their joint communique.

Etain Tannam, professor of international peace studies at Trinity College in Dublin, also noted that the statement included references to “reconciliation.” This was important, she said, as it signaled a recognition of the increasing tensions within certain communities in Northern Ireland, and the need to mitigate them. “President Biden did put that word to the forefront in a way that, before Brexit, I wouldn’t have heard as much,” she said.

Experts said all of this shows some pretty clear pressure on London, which is dependent on its partnership with the US more than ever now that it’s out of the EU. Timothy White, an expert in Irish politics at Xavier University, said in some ways this reflects Biden’s larger worldview, “that diplomacy is the best way for America to pursue its interests.”

He added that Biden is not trying to get directly involved in negotiations between the EU and UK, but is making clear the US objective. “And bottom line is we want the peace that was achieved in the Good Friday Agreement to be preserved,” White said.

Biden has big foreign policy plans, and a lack of resolution on Northern Ireland threatens them

If Biden got a message across to Johnson, it didn’t stop the growing distrust between the EU and the UK from bleeding into the Group of Seven meeting this week.

That summit showcased the fractures in the EU-UK relationship at a gathering that was largely supposed to be about cohesion in the face of threats from the pandemic, climate change, China, and more. Instead, the rift over Northern Ireland, and the obvious tensions between Johnson and EU leaders, took many of the headlines.

The animosity is a threat to Northern Irish peace. But the UK-EU tensions are also undermining his larger foreign policy agenda: Just as the US is trying to repair its friendships in this trans-Atlantic relationship, tensions are rising between two critical partners in that arrangement.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22663698/GettyImages_1233397256_copy.jpg) Jack Hill/Getty Images

Jack Hill/Getty Images“There’s a sense that the two sides should figure out the differences so that they can at least avoid more tension between the UK and the EU and, rather, promote more unity, and to be able to focus together on what [Biden] sees [as] being the big challenges — countering Russia and China and strengthening the democratic West,” said Erik Brattberg, director of the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The “sausage wars” may sound silly, but Biden will struggle to create this coalition of democracies to serve as a counterweight to authoritarianism if the EU-UK divorce keeps getting in the way. And it’s just a lot harder to sell the vision that the US and its partners are the ones to trust over China when key members of that group are backing out of agreements or engaging in a trade war.

The UK and the EU are meeting for more talks, one of many, many, many discussions the two will have in the aftermath of Brexit. And even as Biden heads back to Washington, experts said he can, and should, continue to engage.

The biggest way he can do that, experts say, is by appointing a special envoy to Northern Ireland, something most of his predecessors did (including Trump). Members of Congress have been pushing Biden to do so. Biden also still hasn’t appointed a UK ambassador, who would be critical to any diplomatic efforts.

The US wants to preserve and reinforce the Good Friday Agreement. It will apply pressure accordingly, but also sparingly. As experts pointed out, despite the high stakes, this is a trade dispute between the EU and the UK, and they’re going to have to do the messy, ongoing work of figuring out their post-Brexit future.

Biden’s job, instead, is to keep this democratic team together. As Kennedy, of UCD Dublin, said, the UK may not be in the European Union anymore, but Biden’s goal is to get everyone aligned, and on the same side, and make clear the stakes if they are not. “That,” Kennedy said, “is also the message to the rest of the world — and especially to China.”