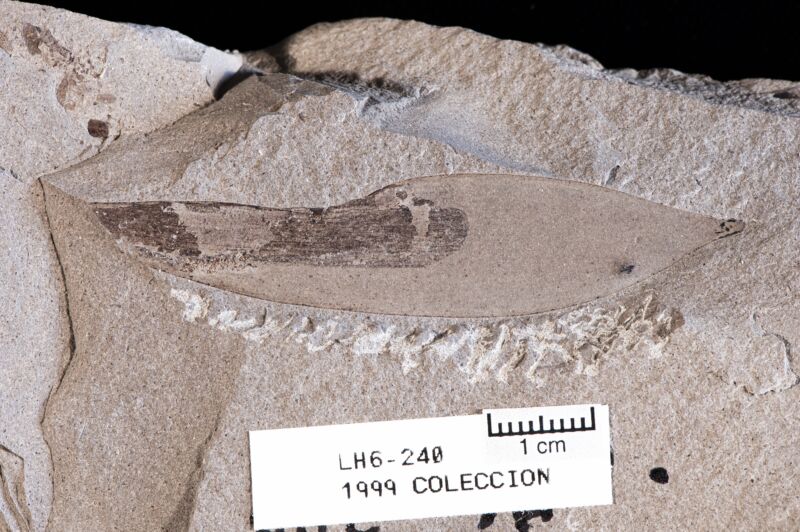

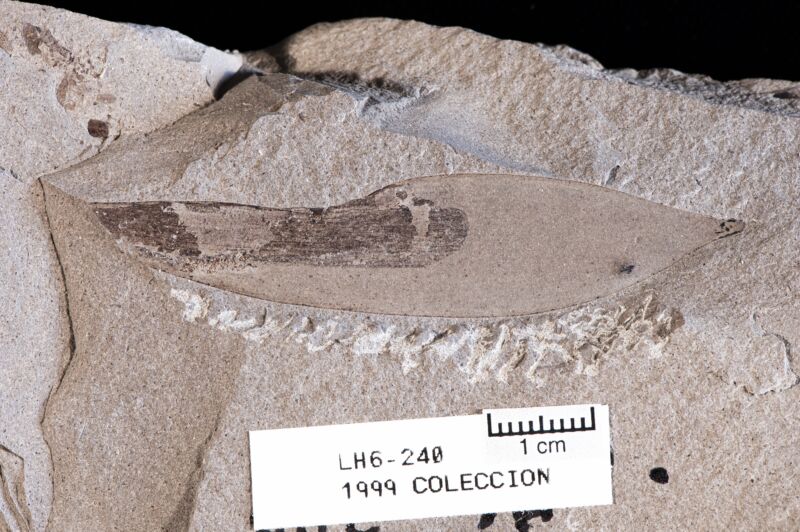

Enlarge / It may not look like much, but you can actually learn a lot from a fossilized leaf that preserves insect damage. (credit: Donovan et. al.)

He knew what it was as soon as he saw it: the signature sign of a bird landing. He’d seen hundreds of such tracks along the Georgia coast. He’d photographed them, measured them, and drawn them. The difference here? This landing track was approximately 105 million years old.

Dr. Anthony Martin, a popular professor at Emory University, recognized that landing track in Australia in the early 2000s when he passed by a fossil slab in a museum. “Because my eyes had been trained for so long from the Georgia coast seeing those kinds of patterns, that’s how I noticed them,” he said. “Because it literally was out of the corner of my eye. I was walking by the slab, I glanced at it, and then these three-toed impressions popped out at me.”

Impressions of toes may seem to be pretty dull compared to a fully reconstructed skeleton. But many of us yearn for a window into ancient worlds, to actually see how long-extinct creatures looked, lived, and behaved. Paleontology lets us crack open that window; using fossilized remains, scientists glean information about growth rates, diet, diseases, and where species roamed. But there’s a lesser-known branch of paleontology that fully opens the window by exploring what the extinct animals actually did.