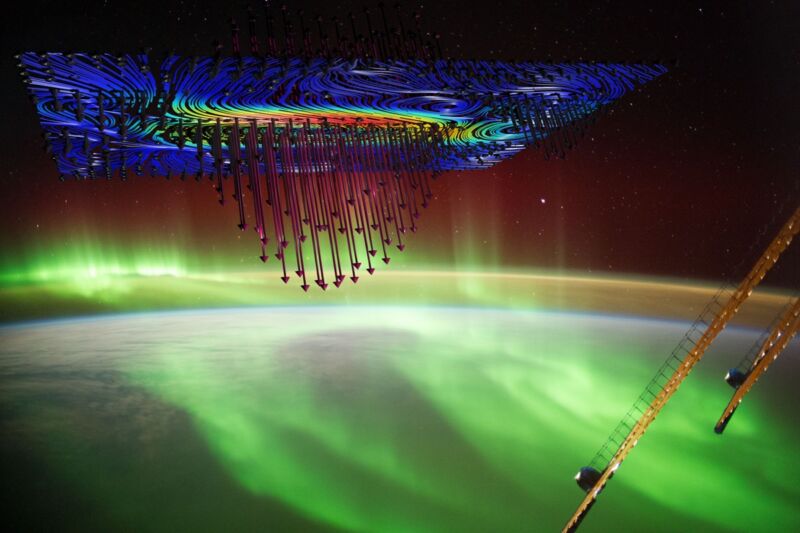

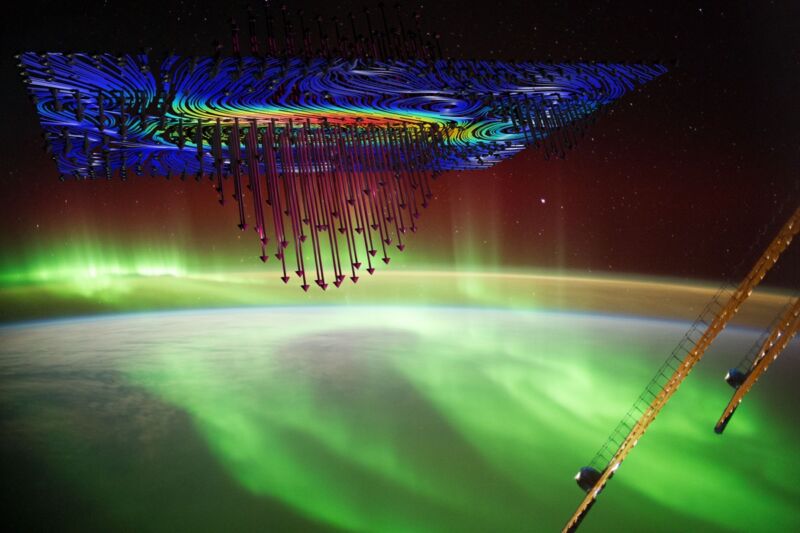

Enlarge / Physicists report definitive evidence that auroras that light up the sky in the high latitudes are caused by electrons accelerated by a powerful electromagnetic force called Alfvén waves. (credit: Austin Montelius, University of Iowa)

In August and September 1859, there was a major geomagnetic storm—aka, the Carrington Event, the largest ever recorded—that produced dazzling auroras visible throughout the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia. Scientists have long been fascinated by the underlying physical processes giving rise to such displays, but while the basic mechanism is understood, our understanding is still incomplete. According to a new paper published in the journal Nature Communications, electrons in the Earth’s ionosphere catch a plasma wave in order to accelerate toward Earth with sufficient energy to produce the brightest types of auroras.

The spectacular kaleidoscopic effects of the so-called northern lights (or southern lights if they are in the Southern Hemisphere) are the result of charged particles from the Sun being dumped into the Earth’s magnetosphere, where they collide with oxygen and nitrogen molecules—an interaction that excites those molecules and makes them glow. Auroras typically present as shimmering ribbons in the sky, with green, purple, blue, and yellow hues. The lights tend to only be visible in polar regions because the particles follow the Earth’s magnetic field lines, which fan out from the vicinity of the poles.

There are different kinds of auroral displays, such as “diffuse” auroras (a faint glow near the horizon), rarer “picket fence” and “dune” displays, and “discrete aurora arcs”—the most intense variety, which appear in the sky as shimmering, undulating curtains of light. Discrete aurora arcs can be so bright, it’s possible to read a newspaper by their light. (Astronomers have concluded that the phenomenon that earned the moniker STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) several years ago is not a true aurora after all, since it is caused by charged particles heating up high in the ionosphere.) Scientists believe there are different mechanisms by which precipitating particles are accelerated to produce each type.