As India’s Covid-19 crisis worsens, the diaspora’s connection to family and home has come undone.

I never did manage to say I love you to my grandmother before she died last November, but my aunt read her an essay I wrote about our family as she lay in bed, down to skin draped over bones, a body ravaged by cancer. The day before she died, she had called my father, her son-in-law, in a panic that she was falling. I overheard the call, overheard him telling her not to be scared, and I cowered in the next room, also trying not to be scared. It was the middle of the night for her in India, the middle of a winter afternoon for us in Ithaca, New York. My two toddlers built a Magna-Tiles castle in front of me. I reached for them as I listened. They shrugged off my hands.

Like so many families during this excruciating last year, we had a video funeral — our family in India by my grandmother’s body, the rest of us scattered around the world from America to Australia. We watched in tiny boxes. I caught a glimpse of her body covered with white cloth on a stretcher on the ground, waiting to be loaded into the ambulance to the crematorium. For a few moments, nobody was there with her body. She was alone.

I lowered my screen, rushed down the stairs away from my family, and cried like an animal. I didn’t return to the video funeral. I couldn’t stand it. I sat alone in the dark dining room, fairy lights that we had set up for Diwali and Christmas twinkling cheerfully behind me. A few hours later, I looked at my screen again. The body takes hours to burn naturally, and it was almost down to ash on the funeral pyre as dawn broke. As the sun rose in India, it was bedtime in America.

I went to sleep and awoke knowing, intellectually, that the world now existed without one of my favorite people.

But I have not grieved. The pandemic life I am currently leading never had my grandmother in it. But my non-pandemic life was filled with her. And now I am vaccinated and a return to non-pandemic life was starting to come into sight. But the problem with a pandemic is that it isn’t over for anyone until it’s over for everyone, and right now, for Indians around the world, it’s not over.

Every day, I am greeted with endless images from India that remind me of my grandmother — bodies wrapped in sheets, faces invisible, everything tucked away, lest the virus escapes. The cremation grounds and burial grounds are overflowing, lines of dead bodies wait outside in the heat, loved ones and workers wear PPE and grieve and work in fear. I look at the images and my own experience immediately becomes both intimate and vast, incomprehensible from a distance either way.

My Indian friends around the world and I share stories, condolences, updates, all of us isolated, little islands of sadness around the world. We are all afraid. But many of us are also in countries that are starting to see the end. Vaccines course through our bodies, and our local friends invite us out for unmasked drinks as beautiful spring weather rolls in. We have one foot in hope, one in dread, and we hover in between, lonely.

The last few years, my husband, children, and I had been living in Mumbai, India, where our house still sits empty since we left last year for New York, about the same time that Covid-19 hit. We had optimistically, foolishly, expected to be back within a month. Back then, my grandmother was living in Delhi, less than a two-hour flight away, and I saw her at least every two months.

I would fly to her, she would fly to me. When I reached Delhi by 6 pm on the first day, we would both be wearing her colorful kaftans, drinking wine, eating fried fish and catching up. Like all good grandmothers, she gossiped about others but defended our family to the bone.

She had lived in the same home since 1986, and I grew up next door. I got my first period on her bed, waking up terrified at the large red stains on my yellow nightdress. She had wireless internet installed at her house so I could work. I set up an iPad for her so she could do video calls with the rest of our family around the world. If I slept past 8 am, she would speak loudly to the maid just outside my door so I would wake up and we could have a day out.

Many evenings, she volunteered at the community library in the housing complex. There, the only books that were new were mine — my grandmother had given them stacks of my novels, making sure all the neighbors read my work. In the housing complex and in the library, we would see all the people I have known since I was 3. Some of them now had walkers, many had hearing aids and could still barely hear, the children and grandchildren had moved on to different cities and countries. Spouses had died, tragedies had been survived, joy had been experienced.

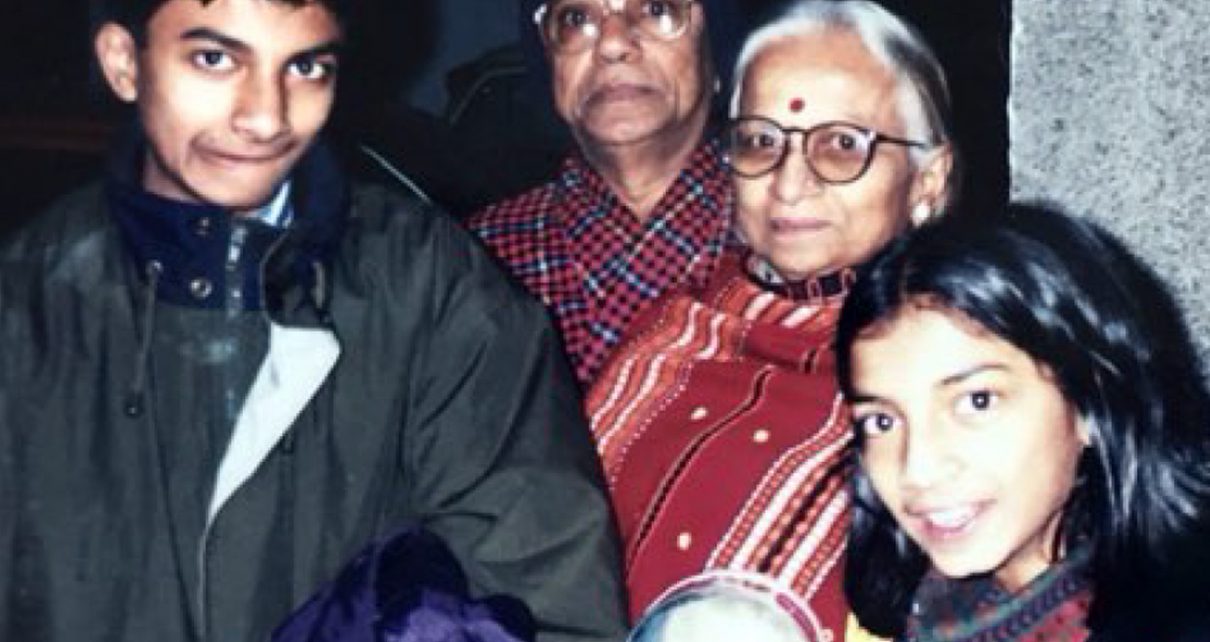

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22520053/image0.jpeg) Courtesy of Diksha Basu

Courtesy of Diksha BasuThis housing complex, this world, these people, are a part of my blood and bones. And now all that ties me to it is my grandmother’s empty home, gathering dust, waiting for us to be able to travel safely to India to do what? Empty it out, I suppose. I am desperate to get there first and to get there alone, but that privilege and burden belongs to my mother and her sisters, the immediate kin. Grief, unfortunately, has a hierarchy.

They have also grieved from a distance. My family is close in many ways but reserved in just as many, and we have not spoken much about our mourning. I have shouted my grandmother’s name into a gorge on a hike. I have cried in my husband’s arms and then wiped my tears and faced my parents. They, too, have done the same. But none of us say any words. I text my brother about it sometimes. He texts me back. He is also in this horrible limbo, unsure where his grief is. But when we call each other, we share jokes and professional updates. I come close to having the conversation with an aunt in Texas. She tells me about how she’s been painting more in memory of her mother. I tell her I taught myself knitting in the same memory. We both talk about how much we want to be like her. My kids barge in and throw a ball at my head, and I hang up, my aunt and I promising each other we’ll chat more regularly.

Every day now is now marked by a series of disjointed conversations and thoughts. A friend in Delhi sends me a WhatsApp message that a common friend, our age, is in the ICU. I look at my phone, unsure how to respond, and set it down before joining a Zoom work meeting in which we all raise a toast to vaccines and a better summer ahead. Another friend messages me asking if I have any contacts at the hospital in Mumbai where our younger daughter was born. I don’t, I tell him, but I send him the number of the doctor who did the delivery and tell him to message her. Then I remember that I haven’t checked on her these past few weeks … I hope she and her family are all okay.

The last time I went to see my grandmother was in early 2020, just as the pandemic hit the news. We went out to lunch at her favorite Café Lota at the Crafts Museum. It was quite a distance from the car to the café, and the guard asked us if we would like a wheelchair. I turned to my grandmother, who immediately scolded the guard and said, “I’m not that old yet.” She held my hand and walked all the way, and we ordered far too much food. I left the next morning, fingering the mask in my pocket, slightly worried about this new illness but with no idea of what was to come. I promised her I would try to visit again the following month.

“Or maybe I’ll come,” she said. “Spend some time with my great-granddaughters.”

She pressed a thousand rupees into my palm. No matter how old or successful her grandchildren became, she would always pay for our taxi ride to the airport after we visited her.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22520057/image0__1_.jpeg) Courtesy of Diksha Basu

Courtesy of Diksha BasuThen the world came to a halt. Now it’s slowly getting back in motion and nothing has changed and everything has changed and my grandmother is dead.

Two months ago, my husband and I whispered in the darkness that maybe it was time to get back home. India seemed under control, we were vaccinated, our children are low-risk. Let’s go back to Mumbai, we said.

I think I want to go to my grandmother’s house alone, I said. Once we’re settled, I could go to Delhi for a few nights and …

I trailed off. Stay in my grandmother’s house?

I need to think about it, I said.

I meant I needed to think about where I would stay in Delhi, but my husband thought I meant I needed to think about whether or not we were ready to return to India. We fell asleep, woke up, and the children had urgent and constant needs. We didn’t book tickets and a few weeks later, India’s second Covid wave came in crashing like a tsunami.

I sleep restlessly all night, waiting nervously for messages from loved ones like I did just months ago for messages from my aunts sitting at my grandmother’s bedside.

I feel guilty that I can’t be there. I feel guilty that I am safe. I feel guilty that I’m grateful.

I will return to an India completely changed. There will be more empty apartments, more empty chairs at family dinners. I will return to friends still struggling with long Covid, friends left without parents and parents-in-law. I don’t know when I will return but eventually, once we settle in and get over the jet lag, I will go to Delhi and the library to see my grandmother’s friends, those who survive the pandemic. Some have already died.

They will hug me and tell me they miss her and I’ll nod. To comfort me they’ll say at least she died of cancer, and not alone at home breathless with Covid. She was one of the lucky ones, they’ll say. At least she didn’t have to wait for hours to be cremated.

I’ll promise them that I’ll still visit often, but I know that I won’t. In my mind, I will promise them all that I will write about them — in some form or another, I will keep them all alive. With my grandmother gone, my own words are all I have left of that life.

Diksha Basu is the author of the novels The Windfall and Destination Wedding.