I looked for a country that got the economic response to Covid-19 right. I found the US.

This story is one in our six-part series The Pandemic Playbook. Explore all the stories here.

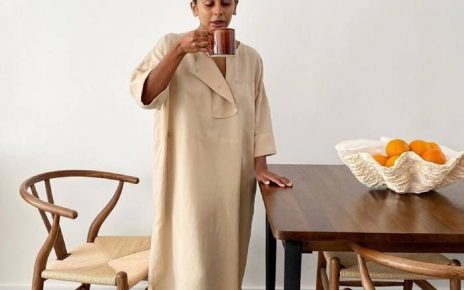

Jasmine Holloway knows it sounds odd. But March 2021, when she and the rest of America were enduring the 13th month of a brutal pandemic, may have been the best month of her life.

When the pandemic hit, Holloway was working at a day care center, taking night classes at the University of the District of Columbia, and raising her three kids.

Initially, the lockdown was a blessing: Suddenly her kids — ages 14, 5, and 3 — were at home where she could watch them more easily. Her 14-year-old, who had been arrested in a particularly rough period shortly before lockdown, found the time especially beneficial. “All the bad influences he was doing before, it stopped because the world stopped,” Jasmine recalls.

But the juggling act eventually took its toll on Holloway. It got so stressful that a bald spot began to grow on the back of her head.

Then more terrible news: In mid-February, a few days before her birthday, she lost her job.

But instead of hitting rock bottom, something strange happened: Holloway started making more money. First, she was able to easily enroll in food stamps and DC’s cash assistance program. Getting unemployment insurance took a bit more work, but once she signed up, she started getting weekly checks larger than the paychecks she was getting from the day care center, thanks to the $300-per-week unemployment bonus — that is, $300 on top of the typical amount — included in President Joe Biden’s relief plans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479833/Dee_Dwyer_Vox_Jasmine_Holloway_2.jpg) Dee Dwyer for Vox

Dee Dwyer for VoxThere was also a one-time check for $5,600 — $1,400 for her and each of her three kids —as part of the most recent round of stimulus. And another $850 a month, $300 each for her 3- and 5-year-old and $250 for her 14-year-old, is coming, thanks to the fully refundable child tax credit Biden enacted.

For Holloway, who spent some time in foster care growing up and currently lives in DC’s Ward 8, a historically disadvantaged area east of the Anacostia River, the pandemic wound up leading to a period of unprecedented prosperity. The pandemic relief “has enabled me to do things I’ve only dreamed about doing for my family,” she says. “I’m getting passports for my children so that when the world opens back up we can travel.” She wants to take them to a Nickelodeon resort in the Dominican Republic. At the very least, she wants them to experience flying on a plane. She’s socking away the weekly $300 bonus for a rainy day. The bald spot on her head has completely grown back.

“Before me being let go, I thought, ‘I need to find other ways to make money, to get to my goals fast,’” Holloway recalls. “Never did I think me being laid off would be what did it.”

Holloway is not alone. For millions of Americans, the pandemic has been a nightmare. But many have also found that the country’s safety net actually caught them.

In March 2020, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed into law the CARES Act, which sent out no-strings-attached checks to the vast majority of Americans for the first time. The bill also dramatically increased the generosity of unemployment insurance, making many workers whole and, for some months, leaving most workers (including Holloway) with more money than they would have earned at their employer. It paused evictions and created a new near-universal child tax credit reaching the poorest families with children.

Then lawmakers did it again in December 2020, passing another bill that offered bonus unemployment benefits and one-time $600-per-person checks.

Under President Biden, the government passed yet another bill, with one-time $1,400-per-person checks, another bonus unemployment measure, and hundreds of billions in relief money for state and local governments.

The result? The poverty rate in the US fell in early 2020. The government did so much to assist its citizens that many people were left financially better off than before the pandemic.

As an American who supports large government intervention to help those in need, I’m used to envying other nations’ governments. I envy European universal health care systems, France’s crèches for child care, and Finland’s success at reducing homelessness.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22476838/GettyImages_1231651417.jpg) Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty ImagesWhen my editors asked me to write a story for our Pandemic Playbook series on the country that I thought “got Covid-19 right” economically, I immediately looked abroad. I spent a few weeks researching and writing about Japan, which has kept unemployment low and spent big to fight the economic downturn.

But as I was working on my Japan article, the US adopted Biden’s American Rescue Plan, a $1.9 trillion behemoth of a bill. With that step coming after the two Trump relief bills, the US just about matched Japan’s spending to fight the downturn. And as I looked into the details, it became impossible to deny that the US spent the money better.

To be sure, it’s not as simple as that. Would I rather have been in Japan for the outbreak or in the US? In public health terms, the answer was obvious: Japan has kept the virus under control vastly better. But in economic terms, the answer was also obvious: The US was more generous.

The comparison seemed even more favorable as I looked to Europe, which botched the virus on a public health level in a manner similar to the US, and offered less extraordinary support to its citizens. Most European countries have stronger safety nets to start with, but they largely didn’t use the pandemic as an occasion to strengthen them. The US did.

No country handled the economic shock of Covid-19 perfectly. Every country, the US included, made mistakes, sometimes grave mistakes. But a detailed comparison suggests that the US had the strongest economic response to the pandemic, in terms of providing income to its citizens during lockdown and ensuring a strong, rapid recovery as the economy began to reopen.

“The US will come out of this economically better than any country that was similarly affected by the virus,” Jason Furman, an economist at Harvard and former chair of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, says.

The US passed some of the biggest Covid-19 relief packages in the world — and targeted those who needed the most help

When it became clear in March 2020 that the coronavirus would necessitate lockdowns across the world, policymakers immediately saw the event as the biggest economic crisis since the 2008 recession, or perhaps even since the Great Depression.

Because of the need for social-distancing procedures, businesses like restaurants, sports arenas, and movie theaters would need to be shuttered. But the hit was much broader. Orders of raw materials from metal to soybeans collapsed in March. The worst week for new unemployment claims in American history, in fall 1982, saw 680,000 people claim benefits for the first time. The week ending March 21, 2020, saw 3.3 million, more than four times the previous record. And the weekly tally stayed above 1 million for months.

This was an economic crisis of unprecedented speed and ferocity, one that brought predictions of enduring Great Depression-scale unemployment for months or years to come.

In the US, at least, that prediction (made by, among other people, me) seems to have been wrong. The country is recovering quickly from the economic shock of the pandemic.

And we did so despite botching our response to the crisis itself. Using aggressive social distancing, testing, and contact tracing to contain the virus — as nations like South Korea and Australia did early on — had huge economic benefits, and the US’s failure to contain its outbreak had enormous economic costs.

But many other large, rich countries also botched their response to the pandemic. If you compare the US to the five most populous countries in Europe, it fares roughly the same in terms of deaths from Covid-19. Germany does better, but the UK, Italy, Spain, and France are right there in the muck with the US.

If this past year is any indication, countries are not always going to be able to contain future pandemics. If and when that happens, they need to be able to manage the economic fallout.

A blunt, but useful, way to see if they managed the fallout successfully is to measure how much countries spent on stimulus measures. Pinpointing this number is tricky, and reputable researchers have produced a number of different estimates.

Christina Romer, a former chief economist to President Obama now at UC Berkeley and an expert on downturns, put together her estimates in a recent paper presented at a conference hosted by the Brookings Institution. She only looked at “early packages,” defined as stimulus passed before July 31, 2020. The US dominated the list, outstripping every peer country in the scale of its response, with only New Zealand really coming close.

Another estimate, this time drawing from International Monetary Fund data, comes from economists Ceyhun Elgin, Gokce Basbug, and Abdullah Yalaman. Their estimates include policies through March 2021, which takes into account the $1.9 trillion Biden package. Here, too, the US spending surpasses its European peers, though the authors estimate that Japan spent vastly more, around half of its 2020 GDP.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479794/covid_19_gdp_countries.jpg)

But the Japan figure is arguably misleading; Peterson Institute for International Economics researchers Madi Sarsenbayev and Takeshi Tashiro have argued that the Japanese government has recategorized ordinary spending as Covid-19 relief, and that an apples-to-apples comparison would show US spending of 27.09 percent of GDP as compared to 29 percent in Japan.

Regardless of the numbers you use, the US is near the top when comparing countries for the scale of their stimulus responses. What makes the US response more unusual is its focus on spending to increase the incomes of its residents, as opposed to backstopping businesses.

This shows up in data on disposable income, a component of GDP that measures the money available to spend by individuals and households. Almost all rich countries measure this quarterly, enabling us to see what happened to individual incomes across countries during the crisis. In the US, government support enabled a surge in disposable income in the second quarter of 2020. In other large rich nations, like France and Germany, it fell sharply (though Canada’s rose a similar amount as the US).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479536/disposable_income_per_country.jpg)

The US’s drawdown of stimulus in the third quarter caused the increase in disposable incomes to shrink, but it was still well ahead of its peer nations.

So the US spent big, and individuals and households reaped a windfall. But simply spending big isn’t good on its own. It’s valuable if spending enables a country to catch up to its economic potential and return to its trajectory pre-Covid-19.

That’s precisely what the stimulus measures — particularly Biden’s March stimulus — did.

Brookings Institution economists Wendy Edelberg and Louise Sheiner estimated the likely trajectories of US GDP with and without the $1.9 trillion injection. Without it, they estimated that the US would not return to pre-pandemic economic trends until after 2023 — akin to the long, slow recovery that followed the 2008 financial crisis. But with the Biden package, they project the US will be back on trend by the end of this year.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479542/projections_real_gdp.jpg)

The effects of the stimulus are, of course, debated. The sheer scale of the stimulus drew substantial criticism from deficit hawks, who worried about the long-term cost of adding $1.9 trillion to the national debt. As it stands, this does not appear to be a major problem; investors are buying up 30-year federal bonds at real interest rates near zero, meaning the government can, in principle, delay paying the bill on the stimulus package for three decades without paying any interest.

But it’s striking that the most common critique from economists is not that the stimulus is inadequate for combating the downturn, but that it’s too much. Larry Summers, the Harvard economist and treasury secretary under President Bill Clinton, has warned that Biden could push spending so high that businesses start running out of the capacity to produce goods and services, sparking inflation.

By contrast, few other countries seem to be aggressive enough to risk overheating. The downturns in America’s peer nations have tended to be deeper, and the recoveries slower. The IMF estimates that the US lost 3.5 percent of GDP in 2020. Compare that to an average of 6.6 percent across the eurozone, including 8.2 percent in France, 11.1 percent in Spain, and 9.9 percent in the UK. These countries did not just suffer more than the US, they suffered two to three times as much. Canada and Japan, at 5.4 and 4.8 percent GDP loss respectively, were not as bad as their European counterparts, but still worse than the US.

Put it all together and the GDP picture in the US is much, much better than its peer nations.

“America is going to win this the way we won World War II”

Furman, the former Obama economist, has some misgivings about specific aspects of the US fiscal response to the pandemic. He thinks the US could have done roughly as well while spending a bit less money. But that might just be part of the reason the US succeeded during this crisis.

“America is going to win this the way we won World War II,” he told me. “Everything was larger than it needs to be, duplicative, just throwing lots of stuff at [the wall]. … But you won the war.”

Reasonable people can disagree on whether the fiscal programs to assist Americans during 2020 and 2021 were excessive or merely generous. What’s inarguable, though, is that they were massive, and enough of them worked to make the overall economic response incredibly strong.

The most distinctive, and easiest to compare, part of America’s response was the stimulus checks. The US government has by this point sent out three rounds of “economic impact payments,” or stimulus checks. The March/April 2020 round was $1,200 per adult and $500 per child dependent; the December 2020 round was $600 per adult or child dependent; the March 2021 round was $1,400 per adult and child, including adult dependents with disabilities and college students.

For a family of four like Jasmine Holloway’s, those checks added up to $10,700 over the course of a year — a life-changing sum of money.

This was a remarkable aspect of the US response for two reasons. First, it had never happened before in American history. In 2001 and 2008, President George Bush sent stimulus checks to American households, but the policy deliberately excluded the poorest Americans. Meanwhile, both the Trump and Biden checks were designed so that all Americans below an income cap could receive it.

More strikingly, the checks were a distinctive policy internationally. The US, South Korea, and Japan were the only large countries to send checks to the vast majority of their citizens; Hong Kong and Singapore did something similar, but peer nations like the UK, France, and Germany did not.

And the US sent much bigger checks than Japan or South Korea did. If Jasmine Holloway lived in Japan, her family would have received about $3,800, or about one-third of what she actually received in America; in South Korea, she would have received 1 million Korean won or $1,151, far less. Even if you adjust for the fact that South Korea and Japan are poorer on a per-capita basis than the US, they sent out less.

America also distinguished itself by its incredibly generous approach to unemployment insurance. The UI system in the US is quite antiquated and rickety, relying on state-level systems that barely coordinate with each other and were not at all ready for the surge in applications that came in spring 2020. Policymakers wanted to expand the generosity of the program in percentage terms — to replace, say, 80 or 100 percent of workers’ wages for the duration of the emergency — but the system’s poor infrastructure made that impossible.

Ron Wyden (OR), then the Senate Finance Committee’s ranking Democrat and a primary author of the unemployment provisions in the CARES Act, explained that the choice to just tack on $600 each week to every unemployment check was an attempt to achieve “rough justice” in lieu of the ability to pay a set percentage of incomes.

The result was a system that was not merely generous — it was a great deal more generous than any of our peer nations.

University of Chicago economists Peter Ganong, Pascal Noel, and Joseph Vavra estimated in the summer of 2020 that the $600 bonus checks meant that overall, the typical out-of-work American saw 145 percent of their wages replaced. That replacement rate fell when the $600 bonus expired at the end of July, but it surged when $300-per-week bonuses were revived, first temporarily in September and then on a more ongoing basis in December (and even more when the Biden stimulus added another $100-per-week for health premiums).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479543/replacement_rate_2.jpg)

Right now, with the $300 bonuses, the median replacement rate is close to 100 percent, far higher than unemployment offers in any of America’s peer countries.

Most countries relied less on unemployment insurance than on “job retention schemes,” which have become incredibly popular internationally during the pandemic. Under such programs, companies can reduce hours for workers (sometimes to zero) and get a set percentage of their labor costs paid by the government, so workers are still taking home pay. Some countries with existing programs — Japan with Employment Assistance Subsidies, Germany with kurzarbeit, and France with activité partielle — made them more generous during the pandemic; other countries like the UK and Denmark created new ones.

Researchers at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of largely developed nations, put together an October report comparing these schemes and, in particular, comparing their “replacement rates” — the share of pay that workers retain under the scheme, even if they’re working less or not at all. The replacement rates in the programs varied but were generally in the 60-90 percent range: 70 percent in France, upward of 87 percent in Germany, 75 percent for larger firms and 100 percent for smaller firms in Japan. Generally, the programs also had a cap on total government support per worker, so high-wage people would get less than the set replacement rate.

In other words, you would most likely get more money under the US unemployment system than under one of these job retention schemes. The US’s initial 145 percent replacement rate and its roughly 100 percent rate now blow countries like France out of the water. The US bonus UI approach has, for most of the pandemic to date, put more money in the pockets of its citizens than the European job retention schemes did.

You can see the effects of this in America’s poverty statistics. Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy researchers Zachary Parolin and Megan Curran have been tracking poverty during Covid-19 on a monthly basis, and found that for much of the pandemic, poverty rates have been below their January 2020 level, largely due to stimulus relief.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479577/monthly_spm_poverty_rate.jpg)

Economists Bruce Meyer, Jeehoon Han, and James Sullivan have their own poverty tracker, which shows poverty falling sharply in the spring as stimulus checks and bonus UI payments went out. It ticked up again when UI payments expired, before falling again with another round of stimulus in December.

So America was not just more generous than its peer countries, it took the crisis as an opportunity to cut poverty.

A good economic response — but not perfect

None of America’s successes in shoveling money to citizens during the pandemic should obscure its many failures.

The most important by far was its failure to control the virus. If the US had used aggressive social distancing rules, widespread testing, and contact tracing the way nations that successfully contained the virus like South Korea did, it would not only have lost 550,000 fewer lives, it would also be stronger economically.

A group of Korean researchers explains that because South Korea crushed the virus early, it was “able to avoid some of the severe long-term restrictions, such as lockdowns and business closures, that have led to troubled economies in many high-income countries.” By October 2020, the South Korean economy was growing again. That matches what analyses early in the pandemic were telling us. Lockdowns and test-and-trace are costly in the short run, but if implemented aggressively, they do not have to last long. And if they contain the virus quickly, the economy wins on balance.

Beyond that failure, the US response was too haltingly paced. The federal unemployment bonus was $600 per week from March through July, then $0, then $300 per week for six weeks in the fall, then $0 again, then $300 per week starting in December, then another $100 per week for help with health care premiums starting the following March. Those changes reflected gridlock in Congress, not the reality of the virus, and created harmful uncertainty for people pushed out of the workforce.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22476881/GettyImages_1231635962.jpg) Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call via Getty ImagesThe loan programs for businesses included in the March 2020 stimulus package were a fairly mixed bag. The most famous, the Paycheck Protection Program, was geared toward small businesses and offered forgivable loans for businesses that pledged to keep workers employed. In that way, it attempted to mirror European job retention schemes, albeit for a subset of workers.

Did it work? It depends on who you ask. An early analysis by Harvard’s Opportunity Insights lab found the program “had no meaningful effect on unemployment” through the middle of May. Ten economists found in a July MIT paper that the program increased employment by about 2.3 million workers through the beginning of June — not that many, given the size of the US labor force.

But Columbia’s Glenn Hubbard and the American Enterprise Institute’s Michael Strain found a more significant positive effect on small business employment. University of Maryland economist Michael Faulkender, then serving as assistant secretary of the treasury for economic policy, and treasury economists Robert Jackman and Stephen Miran found a fairly massive effect: 18.6 million jobs saved.

Adam Ozimek, an economist who also co-owns a bar/arcade/bowling alley in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, which received a PPP loan, has bemoaned how complicated the system is but argues that it played a useful role. “The extent to which PPP worked should be judged not on short-term employee retention,” he told me. “It should be judged on whether it helped reduce the business failure rate. I believe it did, given the surprisingly low business failure rate we most likely saw this year.”

The $454 billion lending program the March 2020 stimulus set up for mid-sized and large businesses, by contrast, seems to have been largely superfluous. It was set up to be run by the Federal Reserve and to enable riskier loans to be made to firms at risk of collapse, but by August, more than half the money was still unused. Corporate bond yields fell to record lows, so most large companies were able to borrow to finance their operations quite cheaply. The program didn’t actually cost any money; it arguably wasn’t particularly needed, and the $454 billion it added to the sticker price of the CARES Act could have been better used.

How to prepare for the next downturn

For all those failures, the US economic response to the crisis was overwhelmingly successful — and there’s no better evidence of that than the experience of people like Jasmine Holloway. The US didn’t do everything right during the pandemic. But it saved her and her family — and left her better off than pre-pandemic. And she’s hardly alone in that respect.

The question for the US is whether Americans want this to be a one-off success — or something more enduring.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22479841/Dee_Dwyer_Vox_Jasmine_Holloway_7.jpg) Dee Dwyer for Vox

Dee Dwyer for VoxThere are a few ideas policymakers need to take seriously to cement the gains the country saw this past year. For one thing, America could stand to have a better unemployment system than the fractured, complicated one we currently have. People like Holloway found the system frustrating and time-consuming to access, and its generosity fluctuated seemingly at random. Recent proposals for reforming the UI system seek to make it so that it’s more heavily federally financed, automatically lasts longer during recessions, and is more generous week-to-week during recessions. (Wyden and Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) have also proposed legislation around these lines.)

The US could also experiment with a real job retention scheme, like the ones many other countries use. Those programs were markedly less generous than the US unemployment insurance system during the crisis, but their structure was arguably superior, as it let workers stay on their employer’s payroll.

The US has a system meant to work like this — 27 states and Washington, DC, offer “short-term compensation” or “work-sharing” programs through the unemployment system — but it’s a mess. Shortly before Vox Media announced layoffs in the summer of 2020, some of my union comrades and I devised a work-sharing plan to avert the lost jobs. But getting the plan to work was a bureaucratic nightmare, involving different applications in different states, and excluding employees outside of states that didn’t offer them. The company ended up not pursuing it. A well-designed version of work-sharing could be a huge help in the next recession. There are other ways to make the future pandemic response more robust.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22476886/GettyImages_1231636334.jpg) Samuel Corum/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Samuel Corum/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesEconomist Claudia Sahm has proposed automatically triggering stimulus checks when the unemployment rate rises. Furman, Matthew Fiedler, and Wilson Powell III have proposed having the federal government automatically increase Medicaid funding to states during downturns. Economists Hilary Hoynes and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach have proposed the same for food stamps, and Georgetown’s Indivar Dutta-Gupta has a plan for a similar trigger in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash welfare program.

Better still, America could choose to strengthen its safety net not simply in a time of extreme crisis, but on an ongoing basis. The Biden administration has proposed extending the expanded child tax credit, which offers parents like Holloway $3,600 a year for each of their kids under age 6 and $3,000 for older kids through 2025 at least — and some in Congress want to make it permanent. That way Holloway would have ongoing support for babysitting, her continuing education, and activities for her 14-year-old that fall on the right side of the law.

Holloway says she is incredibly grateful for the support she’s gotten during the pandemic, but she expects and plans for it all to go away. “I know one day we’re going to wake up and all these things aren’t going to be here,” she told me. For some programs, that’s probably appropriate. Covid-19 was a unique crisis in need of unique remedies.

But what if some of the help wasn’t snatched away? What if families like Holloway’s could rely on some cash support from their government, not just this year, not just in a time of crisis, but every year, as a basic right of citizenship?