Senegal’s quarantine policy sought to slow transmission, and local health care workers battled the pandemic from the ground up.

This story is one in our six-part series The Pandemic Playbook. Explore all the stories here.

DAKAR, Senegal — Aissatou Diao talked about Covid-19 a lot. How to socially distance, what to do if you have a cough or a fever. But when the first coronavirus case arrived in Yeumbeul, a village outside Dakar where she does health outreach as a community relay, she couldn’t believe it.

“I almost died when I heard I was on the list of people who were in contact with the Covid patient,” Diao recalls.

That single contact brought Diao to Novotel, an upscale hotel in Dakar with Atlantic Ocean views. As part of its pandemic response, Senegal sought to provide a bed to everyone with Covid-19 — including mild or asymptomatic cases — and their direct contacts. In the spring of 2020, for about six months, Red Cross volunteers replaced hotel staff at Novotel, and rooms filled with people like Diao, exposed to Covid-19 and sent away to isolate.

Her fellow community relays, who did Covid-19 outreach with her, kept calling and calling to check her status. They wanted to know if they’d be next. “We all got ready with our luggage, waiting for the results,” one of them said.

Diao tested negative, twice, and she left quarantine after just four days. A year later, she calls it a funny story: a short stay in quarantine as she tries to make others aware of the seriousness of Covid-19.

Diao’s experience captures both sides of Senegal’s Covid-19 response. The West African country used aggressive interventions like this isolation policy to slow transmission. At the same time, community and local health actors bolstered the public health response from the bottom up, relying on longstanding relationships and trust to convince people to wear masks, seek out testing, and get treatment.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468548/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_48.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468564/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_51.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468565/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_52.jpg)

“We have what we call a ‘chain of solidarity’: The nation joined hands together,” Moussa Seydi, chief of infectious disease service at Dakar’s University of Fann Hospital Center, said. “Religious leaders came to join the political decision-makers, and also, the community involved themselves in giving this response to Covid-19.”

Vox reported in Senegal at the end of March, just a little more than a year after the country detected its first Covid-19 infection. In Dakar and in the surrounding districts, we spoke to government and local officials, public health experts, doctors, nurses, community leaders, and volunteers to understand how Senegal’s early action from the government and the community buttressed a fragile health care system. This article is part of The Pandemic Playbook, Vox’s exploration of how six nations developed strategies to fight Covid-19.

Senegal’s early policy of isolating people in treatment centers or hotels — combined with other top-down public health measures, such as curfews, mass gathering bans, and temporary school closures — sought to slow transmission in a place that has limited hospital beds, doctors, and resources. A 2017 World Bank study estimates that Senegal only has seven doctors per 100,000 patients. The United States, by comparison, has about 260 physicians per 100,000 people.

The country relied on its experience battling other outbreaks, from the Ebola epidemic in 2014 to HIV/AIDS, to prepare and act early. Senegal depended on local leaders and health agents, all front-line workers, often with multiple job descriptions: communicators, contact tracers, caregivers. They tried, and sometimes struggled, to make the Covid-19 policies work in their communities. They handed out masks. They went on local radio to talk about the coronavirus. These tiny acts, replicated from neighborhood to neighborhood, helped persuade a public to comply with public health measures.

“When we talk to the population and tell [them] to face this Covid, it’s the community who can do it,” Abdoulaye Bousso, the director of Senegal’s Health Emergency Operation Center, who helped lead the country’s Covid-19 response, said. “It’s not the health system, it’s the community.”

Those interventions helped Senegal withstand a first wave, with fewer than 15,000 cases and just over 310 deaths by the end of September. By then, the country had relaxed many of its most stringent policies, a combination of its early success and a growing recognition that cost and sometimes fierce public backlash had started to make those measures unsustainable.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468884/GettyImages_1213154639.jpg) John Wessels/AFP/Getty Images

John Wessels/AFP/Getty ImagesThose trade-offs, along with a false sense of security and the toll of restrictions, may have helped fuel a more potent second surge in Senegal, one that tested the country’s health system. Senegal has now recorded more than 40,000 cases in the pandemic, out of more than 4 million recorded in Africa, and just over 1,000 deaths have been confirmed. But the country — and its communities — responded to the surge, and cases have declined steadily since their daily peak of about 460 in mid-February.

Other factors likely played some role in the country’s relatively low death toll so far. About 60 to 70 percent of Senegal’s population is under 35, likely leading to more asymptomatic or mild spread and less severe disease than in nations with older populations. Senegal’s testing is rapid, but the country still faces limits on its testing capacity, so many cases are likely unrecorded. Some early serological studies point to much greater community spread than the official numbers show. And there are plenty of unexplained disparities between poor and wealthy countries, and between different regions, that we still don’t fully understand.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22473833/senegal_covid_cases.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox But Senegal was also ready. “People were saying: ‘You all will die with this Covid. Africa will disappear with this Covid,’” Seydi said. “Africans got so scared that they didn’t have any other choice but to prepare themselves. More than usual! And this preparation contributed to the fight against this disease.”

Senegal prepared for Covid-19 by looking to a much more lethal disease

The 2014 Ebola epidemic left a grim wake in West Africa. It sickened 28,000 people in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Nearly half those infections were fatal. Senegal recorded its first case that August, a traveler who arrived to Dakar from Guinea.

The Ebola patient was identified, but only days after his symptoms started. Once that happened, he was isolated, his contacts quarantined. Doctors and officials, with help from some international agencies, coordinated care and the response. After one case, and the requisite waiting period, Senegal was declared Ebola-free.

Senegal had contained the outbreak. Abdoulaye Bousso saw all the ways it might not have worked. The lesson from Ebola, he said, was that Senegal needed to invest in a permanent emergency response system, something the country wouldn’t have to put together and take down after each crisis. Senegal, like many countries in Africa, dealt with outbreaks and public health challenges all the time. They often had to do so with scarce resources. This was all going to happen again.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22473840/senegal_locator_map.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox After Ebola in 2014, Bousso helped establish Senegal’s Health Emergency Operations Center, which he now leads. It gave Senegal five years to strengthen its system when a new coronavirus was detected in Wuhan, China.

This was “peacetime” preparation, Amadou Sall, the head of Senegal’s Pasteur Institute, said.

“When you’re having an epidemic that is at that scale, all you have to do is reinforce — you don’t have to build from scratch,” he said.

Senegal ramped up those reinforcements in January. “We use the same strategy in Ebola,” Bousso said. “The most important thing is to detect — to test rapidly, to isolate, and to treat patients.”

At the start of the pandemic, the Pasteur Institute in Dakar was the only lab in Senegal that could test for Covid-19, and just one of two labs in Africa that the World Health Organization designated for Covid-19 testing. Fann Hospital, in Dakar, which Seydi oversees and which treated the lone Ebola patient, was the only facility equipped to care for Covid-19 patients at the start of the pandemic. It had 12 spaces with beds to isolate patients when Covid-19 hit.

Testing in 48 hours or less became Senegal’s gold standard. “You want to increase the number of people to test, but you also want to make sure you can deliver in a very short period of time,” said Souleymane Mboup, one of Senegal’s premier researchers and the head of the Institute for Health Research, Epidemiological Surveillance, and Training, whose lab eventually oversaw testing in Senegal’s Thies region and for travelers.

The process also had to exist across Senegal. “We managed to have [field labs in] each of the regions of Senegal, a few labs that were in a position to deliver a test in 24 hours,” Sall said. Senegal never performed as many tests per capita as the United States, but the share of tests coming back positive — one indicator of whether enough testing is being done — dropped quickly in the early weeks of the pandemic, and has, at times, been lower than positive rates in the US.

Quick test results made the isolation policy possible. “We decided that that person should be isolated and put in quarantine,” Mamadou Ndiaye, the director of prevention at the Senegalese Ministry of Health and Social Action, said. “This was the best way we could limit the transmission of the virus among the community.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468899/GettyImages_1210833718.jpg) John Wessels/AFP/Getty Images

John Wessels/AFP/Getty ImagesRather than ask people to quarantine or isolate at home, the government put coronavirus patients, regardless of severity of symptoms, and their contacts in separate facilities to limit the possibility of transmission.

Senegal needed beds to do this, and people to take care of patients. Seydi and his team trained personnel across Senegal. The country added beds where it could to hospitals and health care facilities. It set up field hospitals. The country expanded its maximum capacity to 1,500 beds. That figure does not include hotels, emptied of guests, which mainly became quarantine centers for people who had been in contact with a Covid-19 case. More than 3,200 Red Cross volunteers helped take care of those in quarantine.

This national blueprint also had to work in each part of Senegal, from Dakar to the country’s rural corners. Senegal has 14 medical regions, subdivided into 79 health districts. The districts have health centers with doctors and nurses. Below those centers are “postes de santé,” or health posts — often staffed with a head nurse and midwife — and health huts, the closest link to the community. Those institutions are all building close relationships with the community, working with volunteers and leaders for outreach and campaigns.

“Anything that happened in one place can be somehow detected and then taken care of by the people at the level where those people are,” Sall said.

Meeting people where they are

When Amy Gningue enters a home, she greets people with “Salaam alaikum” and asks to speak to her cousins. There will always be cousins: Everyone in her community in Yeumbeul counts as a cousin. She was born here, grew up here, got married here. This makes the conversation go a little easier when, after the greetings, and maybe breakfast, she begins speaking to the head of the family, asking questions like, “Are you aware of the existence of Covid-19?”

If the answer is yes, Gningue might ask more questions: “What do you think we can do to prevent the disease?” She wants to start a dialogue: He may say that he’s asking family members not to shake hands, to use hand sanitizer, to wear a mask. But if he doesn’t know all this, Gningue might offer advice: Masks work, and it might help to get some antiseptic gel.

“I do not impose on people,” Gningue said. “When I see someone who is not wearing a mask, I come respectfully to him and ask the reason why he is not wearing masks, knowing they are in danger by not wearing a mask. You see, I have this advantage.”

Her advantage is that she’s the community’s badienou gokh, a neighborhood godmother or auntie. “For some, I am ‘badiene,’ meaning sister to their fathers. For others, I am aunt; for some, I am sister. For other people, I’m just a woman, a wife,” Gningue said. Badienou gokhs also have a formal role in health, often in maternal or reproductive care. Her stature and roots in the community mean her word counts as much as, or more than, what doctors or health officials say.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468918/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_43.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468920/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_33.jpg)

Covid-19 consumed Gningue’s year. She visited with patients. She tried to find assistance for families who’d lost income or jobs. But much of what she does is general outreach, working alongside about 10 community relays, including Aissatou Diao. They target eight districts in Yeumbeul Nord and Yeumbeul Sud, a rural municipality that is still less than an hour outside of Dakar.

“As grown-up children of the community, we are trusted,” Ramatoulaye Ka, who works with Gningue and is the president of the community relays, said.

When Gningue and her colleagues talk about their work, sitting on black couches pushed against each wall of Gningue’s living room, they do so with a mix of pride and exhaustion. They believe they’ve made a difference; when we speak at the end of March, Yeumbeul has not recorded any new cases in almost a week, a point of success for them. It’s been a long year of going door to door, hosting focus groups, telling people to wash their hands and wear a mask.

Those like Gningue have long been a link between the community and the health care system. There may not be a doctor in every village, or a hospital in the region, so this infrastructure exists to connect people to care, whether it’s childhood vaccines or postnatal checkups. Community outreach happens around other diseases, like HIV/AIDS prevention or malaria.

“The pandemic,” Mouhamet Thioune, another community relay and ambulance driver in Yeumbeul, told me, “is just a disease. Like any other disease.”

So they got to work prioritizing Covid-19. They did this in two ways: by raising awareness of Covid-19 and in helping to make the Covid-19 policies — test, trace, and isolate — work across communities.

Consistent messaging from government and public health officials helped these efforts. Ndiaye, the minister of prevention, delivered daily press conferences during the pandemic, and the Ministry of Health and Social Action gives updates each day on cases, hospitalizations, deaths. “The weak points and strong points,” Ndiaye said.

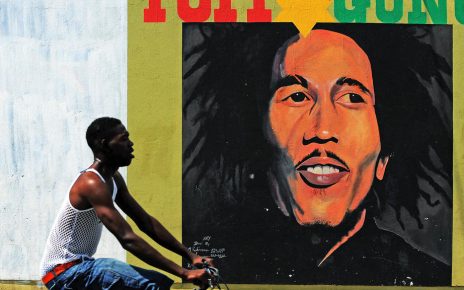

Religious leaders, especially imams in a country that’s 95 percent Muslim, helped reinforce the seriousness of Covid-19, many of them getting on board with mosque closures at the start of the pandemic, or urging social distancing when restrictions were lifted. Some even continued to keep their mosques closed. Graffiti artists created murals; artists rapped in full protective gear.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468953/_MGL3791.jpg) Ina Makosi for Vox

Ina Makosi for VoxCommunity efforts did the same from the bottom up. Badienou gokhs and community relays often helped with tracing contacts, urging people to get tested or trying to convince them to go into quarantine. They were “firemen,” said Ibrahima Niang, president of a network of community leaders in Dakar, intervening when people hesitated about interacting with the health system. Trusted figures like Niang and his fellow leaders tried to persuade them, so that every citizen would understand that they depend on each other in the crisis. We “inform them this is not the end of the world,” Niang said.

“We’re are doing it because there is a process we need to follow to save our communities,” he added.

Daouda Thioub, an infectious and tropical disease specialist and deputy coordinator of the Fann Hospital Epidemic Treatment Center, said that while not everyone would listen to the experts, they would often listen to leaders in the community. When he would talk about Covid-19, he’d appear on local radio, speaking in Fulani, his dialect, rather than French.

“We cannot work against you. We work for you, because we belong to you,” Thioub said. “This was a very effective message.”

Youth groups, women’s groups, savings and loan clubs, and educational groups all got involved. In Notto Diobass, a village near the city of Thies, a youth organization handed out masks and sanitizer, installing hand-washing equipment people could use before entering their homes. The Love Your Husband club, a women’s social group, raised money through its mobile bank to buy equipment, soap, and masks.

“We all felt that we have one enemy to fight. It was Covid,” Ka, in Yeumbeul, said. “We say the whole community join[ed] hands, from community leaders, to politicians, or young people or any kind of association that we have in the district. People come together and join forces to face the enemy.”

It was still not easy work. Especially in the early days of the Covid-19 response, community workers felt they weren’t adequately included in the government’s measures. They fought against misinformation: that Covid-19 was a fake disease, an old person’s disease, a city disease. Thioub said he has had patients who refuse to believe they are sick with the coronavirus. As the pandemic wore on, people became fatigued and frustrated.

And the community relays were fighting not just fatigue and misinformation but stigma — a stigma that, they say, the government’s isolation policy worsened.

Senegal’s Ebola playbook worked — until it didn’t

Youssoupha Thiaw had never done room service like this before: Put the food down on the floor, knock, and run away. “That’s all you could do,” he said in his tiny office at the Hotel Le Ravin, in Guédiawaye, a district outside of Dakar.

Last year, from March until June, his hotel hosted a few hundred people who had been in contact with confirmed Covid-19 cases. There was a short period before the Red Cross volunteers arrived, and his staff helped, dropping off food and doing minor cleaning, like changing the bedding between patients. “We did it badly,” Thiaw said. They rushed the job to get the heck out of that room.

Thiaw was scared, but he understood what Senegal was trying to do: For each Covid-19 case they could take out of circulation, they could break one more chain of transmission. This would tightly control community spread, and it would put Covid-19 patients under the care of doctors and nurses, who could offer treatment that might stave off more severe disease. The more closely managed Covid-19 cases, the less likely Senegal’s health care system could be surprised by an onslaught.

“Isolation was almost perfect,” Sall, of the Pasteur Institute, said. “That has been extremely efficient in monitoring and controlling the disease at the very beginning, I would say for the first three to four months.”

But by June, it was becoming clear that almost-perfect isolation only worked if everyone complied, got tested, knew their contacts. “At a certain moment, we realized that the virus was almost certainly in the community,” Seydi, of Fann, said.

The policy had started to become unsustainable in other ways. Paying for hotels — Thiaw says he received XOF 50,000 per room, or about $90 — is costly. So is caring for people at treatment centers who are mostly fine. It strained testing capacity, as resources went to screening people already in quarantine. Khadidiatou Tine, the head nurse at the Poste Santé de Notto said they often experienced shortages of tests, but they used many on people in quarantine, where few would actually come back positive. “It was,” she said, “a waste of time.” About 60 percent of the Covid-positive patients isolated under the policy had mild symptoms, or no symptoms at all.

The government also struggled to support people who had to quarantine. Senegal’s economy is largely informal; people work day to day. Quarantine means they cannot earn any money. The government tried to provide food staples, like oil and rice, but that help had its limits, often leaving community groups and organizations, including NGOs, to fill the void. And even if people understood the rationale behind the policy, it became a source of frustration and fury in the form of protests. And sometimes fear.

Fear, in particular, as the isolation policy intensified the stigma around getting Covid-19. Diao, the community relay in Yeumbeul, said that after her quarantine, people still believed she had Covid-19, even though she did not. “You are stigmatized. People are like, ‘This is a Covid family. These are Covid children,” Diao said. Her kids, she said, got teased in school.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22469075/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_79.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22469077/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_2.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22469078/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_19.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22469079/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_76.jpg)

That sense of fear was sometimes even more intense for those who tested positive. An ambulance would come to their homes, with a full medical team equipped in head-to-toe PPE. These were Ebola procedures, applied to the coronavirus. Those people, in goggles and white gloves, when you see them, Gningue said, “You say, ‘This is danger.’”

Ndeye Coumba Sene, a health official with the District Centre de Santé Wakhinane in Guediawaye, said people would turn off their phones, or hide from community relays or contact tracers, as if trying to outrun quarantine. When people did test positive, she added, they sometimes were in denial because they feared the stigmatization that might come when they returned to the neighborhood. “The community considered Covid-19 a shameful disease; this was a problem,” Sene said. “And that’s the reason why most of them were very reluctant to be tested, but also — even though they present some symptoms of Covid — they refuse to go to hospitals.”

Front-line community actors and nurses understood that this resistance made Senegal’s Covid-19 response less effective. Gningue said she and others pushed back, urging the doctors and officials to change their approach or risk Covid-19 spreading. They also saw more of a role for themselves in the larger Covid-19 response; they felt if they, not the ambulances, showed up at people’s homes, their neighbors would be more likely to follow the measures.

“The state kept on saying this is a medical battle, so the approach should be health-based. And the community kept on saying this is a community battle, the approach should be community-based,” Niang, in Dakar, said.

Officials like Bousso eventually recognized the fear, and the stigma it generated. “We saw that it’s not necessary to put all those patients in hospital,” he said. “Now we decide to use the home isolation, and the home isolation permits our health system to brace and to not be very stressed.”

All of that shifted the country to a policy of home isolation, meant to quarantine and protect those most at risk of becoming seriously ill.

Those who test positive for Covid-19 but aren’t really sick wait it out at home, unless they are considered higher-risk and might need a treatment center. At home, their cases are monitored, and a doctor will call to see what their temperature is, how their breathing is. Sometimes a mobile unit — usually a doctor, maybe with one other person — will drop by to take vitals. If “the situation of the patients are worsening, [these teams] inform the local medical authorities,” Sene, from the District Centre de Santé Wakhinane, said. Those local authorities are supposed to notify regional medical authorities if a patient now needs a bed, the distribution of which is carefully monitored.

Contact tracing still happens, but it now mostly comes with the advice to stay home unless their status changes. Only those who might be at risk — older adults and those with underlying conditions — are urged to get a test.

It makes a Covid-19 diagnosis, and the aftermath, a lot less dramatic. A doctor might knock on a door, along with a community relay, to tell you to get a test, or that you have Covid-19. “It’s just kind of a visitor coming to inform that you are supposed to have [a] Covid test,” Ka said. “Nobody knows; people are conducting it secretly.”

The confidentiality blunted some of the stigma, even if it did not fall away completely.

“The day the government has decided and the scientists have decided that if your symptoms are not severe, you will be kept at home, and treat[ed] there; that was a tipping point,” Daouda Diouf, the director of Enda Santé, said. “Communities felt that the government is recognizing also their role in addressing the pandemic, in responding to the pandemic.”

The move away from the isolation meant trade-offs. Some were felt during Senegal’s second wave.

In her office, Louise Fortes shakes a cardboard box, white prescription boxes rattling inside. They are donations from Covid-19 patients who’ve left the hospital, recovered. They ask what they can do, and Fortes tells them how to buy the medications.

Those are the good news stories. Because most of Fortes’s patients are now over 60, or have diabetes or some other condition. By the time she sees them on her ward in Dalal Diam hospital, in Guediawaye, they are often already very sick. “Sometimes,” she said, “it’s too late.”

Fortes is the head physician in charge of Covid-19 patients in Dalal Diam, Senegal’s largest treatment center, with 200 beds. She started this role on March 27, 2020, an exhausting anniversary that arrives as Senegal is emerging from its far more brutal second wave. On a Tuesday in late March when we meet, 70 patients are still here, a small slice of the 2,600 patients who have received treatment at Dalal Diam since March 2020. Right now, the Covid-19 ward feels cavernous and empty, like a high school after the last bell rings.

The second wave tested Dalal Diam, though never fully overwhelmed it. Still, between December and February, Senegal saw an increase in emergency cases and, especially, deaths across the country.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468973/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_81.jpg)

Senegal’s Covid-19 response looked very different once the second wave arrived. Most restrictions had lifted; people isolated at home. But as cases and deaths began to climb again, the country had to reckon with the trade-offs it had made as it adjusted its strategies.

Quarantining at home meant the “almost perfect” isolation no longer existed. People did not always comply with the advice to stay home, and some likely just felt they couldn’t, especially for Senegalese who needed to earn money each day. There was an acceptance, if not exactly explicit, that infections would slip through.

The change in isolation strategy accompanied a redirection of testing to symptomatic and mostly at-risk people. This helped guarantee that testing covered those most likely to spread the virus, and those most vulnerable. But it also meant it was much harder to get a sense of the scale of the outbreak, and that the case numbers recorded likely couldn’t account for the true spread of the virus.

“Those who are ill and unknown are not tested — that’s why if we have recorded 200 cases, this might not be a right figure compared to those who are staying home and who have not been tested,” Thioub, the infectious and tropical disease specialist at Fann Hospital, said. Those likely lower-than-reality figures gave people a false sense of security, so they weren’t as vigilant about mask-wearing or social distancing.

After the first wave, in about September and October, Senegal also began to demobilize treatment centers. At that time, cases were low, just low double digits daily. But when cases started to inch up again, Senegal was left playing catch-up.

“The intensity with which we were working during the first wave that enabled us to achieve results has led us to close a certain number of centers that were open, and the staff that were hired had been reduced,” Ndiaye, the minister of prevention, said. “So some centers closed, reducing the staff — and we were surprised with the surge that came later.”

“It took time to reorganize to face the second wave,” Ndiaye said. “We tried to update, to reopen and restart, but it took time.”

The government tried to reimpose some restrictions early this year, declaring a new state of emergency and introducing another overnight curfew in Dakar and Thies, two cities that saw big spikes in cases. But the intensity of the measures, especially for Senegal’s workers, didn’t seem proportionate to the crisis, and people resisted. Some began pushing back against mask mandates, religious ceremonies restarted again, and demonstrators filled the streets.

“The unity we saw when the first wave occurred slowly cracked through the second wave,” Seydi said. The blame, he said, is spread around. “Why the Ministry of Health? Because the Ministry of Health reacted late to the second wave. Why the community? Because the community has been rebelling against the decisions that would be implemented by the authorities.”

Senegal’s Covid-19 response came with difficult choices. But it had to adapt for a drawn-out fight.

The case numbers, but most of all the deaths, woke up many more people to the reality of Covid-19, Tine, the head nurse at the Poste Santé de Notto, said in March. She and her community outreach workers wanted people to take the disease seriously before people died.

Sometimes, she said, she felt like she and her volunteers were fighting alone against the pandemic. The government didn’t involve the community in their early plans. The health post needed donations to obtain basic supplies. Once, early in the pandemic, she and her team of community health outreach workers got chased away because they were wearing T-shirts that said Covid-19.

This has been the reality of Senegal’s Covid-19 fight: trying to leverage its resources and experiences to contain a pandemic that has bested far richer and more powerful countries. Senegal is also digging in for a long fight, one that has implications for the entire globe as new variants emerge. Vaccine distribution has started in Senegal, with about 400,000 people vaccinated. But the country had only acquired about 600,000 doses by the end of March, buying doses from China and receiving a donation from Covax. John Nkengasong, the director of the Africa CDC, has said, in the best-case scenario, just 60 percent of the continent’s population could be vaccinated by the end of 2022.

Senegal did not have the technical or financial tools of richer countries, but it also had no other option. It had to prepare, but it also had to be flexible, and adapt, as the pandemic wore on. “You have to learn how to survive with the means you have,” Mboup, of the Institute for Health Research, Epidemiological Surveillance, and Training, said.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22468980/APRIL_2021_SENEGAL_COVID_RICCI_SHRYOCK_26b.jpg)

Senegal’s response also crashed up against the economic pressures. The country saw anti-lockdown protests last spring. Thousands flooded Dakar’s streets in March for political protests, and many saw the social unrest as tied to the furor and despair over coronavirus restrictions. One economist has estimated that more than 2 million people in Senegal — out of 16 million — have fallen into poverty since the pandemic began. In sheer numbers, the full force of the pandemic will be felt there, and many more people spoke about being out of work, or struggling to find income, than of being sick with, or even scared of, the coronavirus.

“In this country, all we know is hard work and supporting our families,” Amary Lo, a resident of Notto, said. Some of the lockdown measures made that even harder, with negative ripples throughout the community. “We suffered a lot during the lockdown because compensation was not enough,” he added.

The pandemic is not over in Senegal. The at-home isolation policy is still intact. Contact tracers are still tracking people down, cajoling symptomatic or at-risk people to get tested. The second wave looks to be behind Senegal, but doctors worry about another, and maybe another, around the corner. They also worry people will get complacent again, and cases will come roaring back. With a meager vaccination campaign, Senegal will have to grapple with these uncertainties for many, many months more.

In Dakar, during lockdown, Niang and his team of community leaders would take a tam-tam and bang it through the neighborhood, chanting messages about Covid-19 prevention, an on-foot caravan. There was no dancing, no singing, no ceremonies, so you could hear the tam-tam everywhere. People had nothing better to do than come and watch.

The streets are filled again in Dakar. Restrictions were lifted in mid-March. The vaccination campaign is small, and stuttering, but happening. Their groups are still doing their caravans, trying to tell people how to protect themselves from Covid-19. As one of them said, they will continue doing it “until we hear that we’ve recorded zero cases in Senegal.”

Ricci Shryock is an independent journalist and photographer based in Dakar. Since 2008, most of her work has been in West and Central Africa, focusing on the Ebola crisis and migration trends.

Ousmane Balde is a freelance reporter, fixer, and translator based in Dakar.