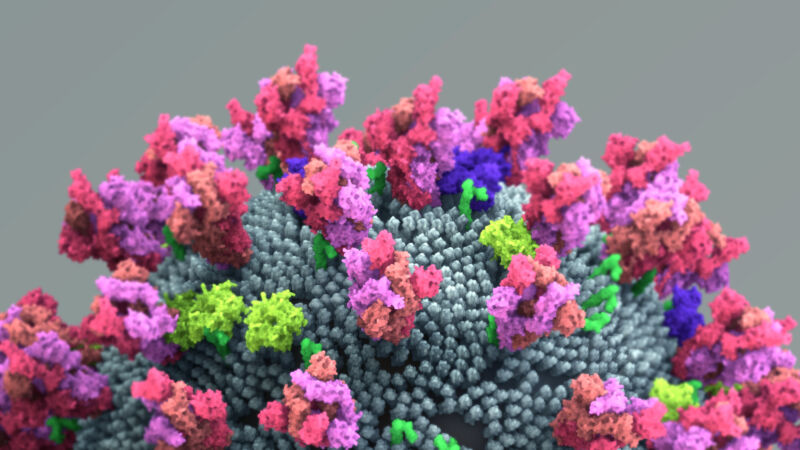

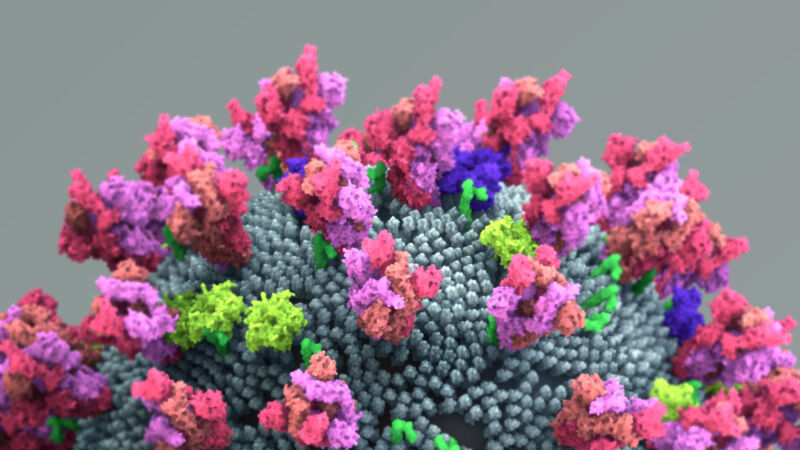

Enlarge / The coronavirus spike protein that mediates coronavirus entry into host cell. (credit: Design Cells / Getty Images)

We’ve always needed to limit the total SARS-CoV-2 infections for reasons beyond the immediate risk they pose to the infected. Each new infected individual is a chance for the virus to evolve in a way that makes it more dangerous—more infective or more lethal. This is true even when an individual has a completely symptom-free infection. The more the virus replicates, the more mutations it will experience and the greater chance that something threatening will evolve.

One of the disturbing discoveries of the past year has been that it’s not just the human population we have to worry about. SARS-CoV-2 has been found in a number of species, notably cats and mink, that we spend a lot of time around. It has even spread from there to the wild mink population, and the virus has jumped back and forth between humans and farmed mink. These animal reservoirs provide added opportunities for COVID to evolve in ways that make it more dangerous to us—perhaps via mutations that allow it to adapt to the new species.

A group of German researchers has now tested some of the mutations that have appeared in viruses circulating in mink populations, and the news is mixed. One specific mutation makes the virus somewhat less infectious to humans but reduces the probability that antibodies raised against the virus will recognize it.