To be legitimate climate leaders on the world stage, the US and China must start by raising ambition at home.

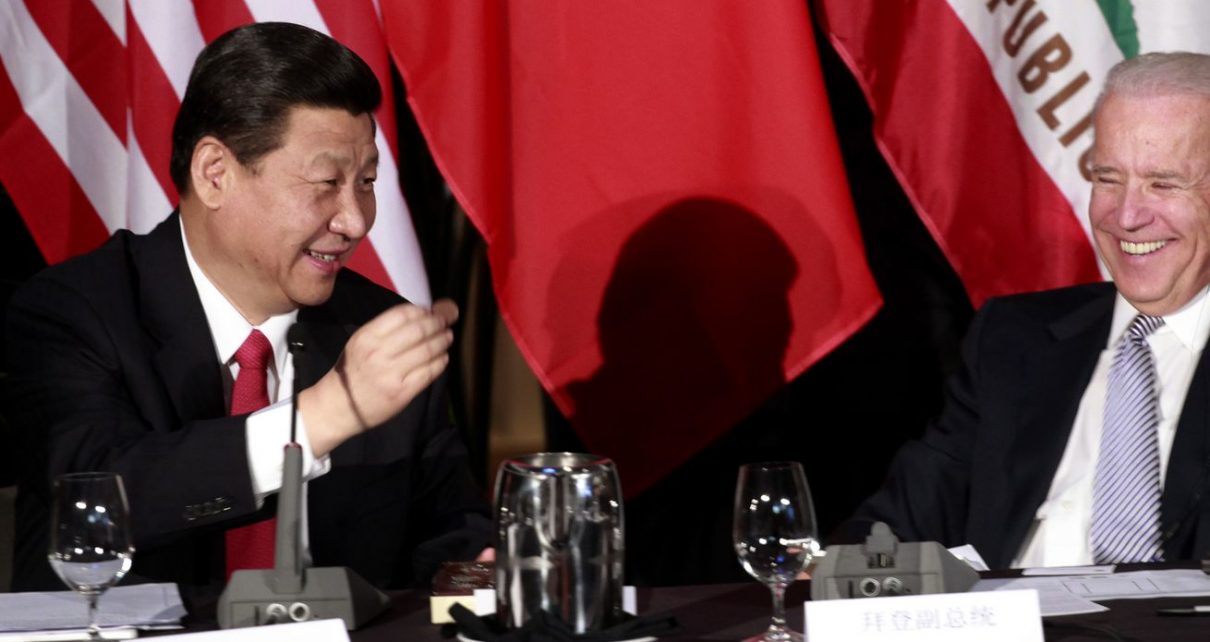

Top officials from the US and China met in Alaska this week for their first face-to-face meeting since President Joe Biden took office. On the agenda was a full range of issues of importance to both sides — not least of which is climate change.

China and the US, the world’s top two economies, together account for 43 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. And while much of the industrialized world is looking to the United States for signaling on climate action, many countries in the developing world look to China for guidance.

“The Biden administration coming into office has been a massive shot in the arm. There are countries around the world that were not planning on increasing their Paris targets this year and are now actively reconsidering that. For example, Japan,” Thom Woodroofe, senior adviser at Asia Society Policy Institute, told me.

“They are doing that because of the Biden administration more so than China, but there are several other countries who will take their lead from China, just as much if not more so. For example, a country like India,” Woodroofe added.

The last time the US and China collaborated on climate change it resulted in the signing of the landmark Paris Agreement. But relations deteriorated under Trump, so there’s work to be done in reestablishing ties.

“Working constructively to bolster these international agreements rather than weaken them, that’s the core part of the cooperation,” Deborah Seligsohn, assistant professor of political science at Villanova University, said.

Appointing John Kerry as the new US climate envoy shows just how eager the Biden administration is to engage and lead the world on climate. A seasoned diplomat, Kerry played a key role in helping to negotiate the Paris Agreement while serving as secretary of state under Obama. Since then, he’s continued to act on climate with his World War Zero Initiative.

And in a positive sign that the country is willing to engage with Kerry, China has appointed seasoned climate diplomat Xie Zhenhua, whose close friendship with former US climate diplomat Todd Stern helped broker the original Paris Agreement.

“Perhaps the biggest signal that [China] wants to find a way to be able to cooperate on climate is the appointment of Xie Zhenhua,” said Woodroofe.

“He’s someone who’s a climate person, not a geopolitical person,” Woodroofe added.

When Kerry first announced that climate could be treated as a stand-alone issue in US-China negotiations, Beijing quickly threw cold water on the idea.

But in a change of heart, during a March 7 news conference state councilor Wang Yi, China’s highest-ranking diplomat, said China would be “willing to discuss and deepen cooperation with the United States with an open mind” on key issues like climate — while taking a hard stance on Taiwan.

So despite a tense relationship between the US and China on several issues, the selection of high-ranking climate diplomats suggests that a careful collaboration on climate may be possible.

“The two sides are talking to each other. The channels are there and have been used in the past,” Li Shuo, Beijing-based policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia, told me in an email. “The question is whether these talks will result in positive outcomes. Climate should provide a safe space for them to conduct an honest conversation. It could, and should, be a stand-alone issue, and not at the expense of other issues.”

With that in mind, here’s how the US and China could lay the groundwork for addressing the climate emergency, and how the US can pressure China to raise its climate ambition.

Work toward “parallel development” on climate goals in each country

As the world’s largest polluters, the most important task is for the US and China to commit to stronger emission reduction targets than currently proposed. The process begins with both countries delivering results at home independently of each other but with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius in mind.

“I see the future being more about parallel development,” Seligsohn, the professor at Villanova, said.

Biden’s $2 trillion climate plan is the most ambitious climate platform of any US president in history, but until it gets signed into law, it’s just a platform.

To reassume climate leadership, “the first thing the US has to do is get our own house in order. We’re not in a good position to ask China to do more on climate change if we have nothing on the books,” Joanna Lewis, director of the Science, Technology and International Affairs Program at Georgetown University, said.

And while China’s announcement of its goal to become carbon neutral by 2060 initially sent major shockwaves throughout the climate world, its 14th Five-Year Plan for economic development left more questions than answers on how the country would get there.

As a central part of the 2016 Paris Agreement, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) indicate what each country plans to do domestically to help achieve the broader goal of limiting warming to 1.5 Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

So more than any high-level meeting or summit, strengthening America’s nationally determined contribution will signal to China and the rest of the globe that “America is back” and put the US in a better position to influence China and other countries to pursue even more aggressive climate plans.

“The most important item [the US and China] need to discuss is their respective climate ambition, as embedded in the Nationally Determined Contributions. We need to see joint enhancement of their climate targets,” Greenpeace’s Li said.

Although relations between the two countries are at their iciest in years, each country working to improve its nationally determined commitment under the Paris Agreement is an effective starting point that will improve its ability to influence the rest of the world.

In December, Chinese president Xi Jinping announced new NDC targets that weren’t ambitious, but the formal NDC paperwork hasn’t been submitted, leaving room for the targets to be strengthened ahead of COP26.

“Once it becomes clear that the US can put forward an ambitious set of climate targets, then there will be increased pressure on China to engage with the US and potentially revisit the ambition of its own climate targets,” Georgetown’s Lewis said.

If Biden can set a stronger US target before his summit of world leaders to address the climate emergency on April 22, there will be more pressure on China to match the level of US ambition. In which case, experts suggest China has two choices.

“One is to do nothing and suffer the cost to its reputation (and potentially further complicate the [US-China] bilateral relationship),” Li said, and, “the other is to further step up ambition.”

“This is a tightrope that Beijing needs to walk,” Li added, noting the difficulty that lies ahead for China. “What’s clear is this will be a top-level decision over the next few weeks.”

The same is true for the Biden administration.

Compete in helping less-developed countries make the clean energy transition

If the US and China are successful in raising their climate goals at home, the next step is to play a leadership role in helping less-developed countries transition to clean energy.

Both Washington and Beijing have indicated that they want to play a role in helping developing countries, but China’s status as a global leader on climate change is complicated by the county’s paradoxical status as both the world’s largest coal consumer and largest renewable-energy producer.

To be considered a legitimate climate leader on the world stage, experts say that, much like the US must also do, China will have to reckon with its pollution.

“China’s leadership will need to understand, before too long, that there is no way for China to maintain and enhance its standing in the world, with rich and poor countries alike, if climate change starts to wreak widespread havoc and China stands out as the dominant polluter who has refused to do what needed to be done,” Todd Stern, the former climate envoy, wrote in a September 2020 article for the Brookings Institution.

China also needs to address the climate impact of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — a massive infrastructure project formally launched in 2013 to increase Chinese influence around the globe. BRI projects are now in at least 140 countries, representing pretty much every inhabited corner of the planet.

Since 2013, the country has invested a total of more than $760 billion in BRI countries with nearly $300 billion going to energy investment, according to data from the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker.

There are even plans to build a Polar Silk Road using Arctic shipping routes, which the recent loss of year-round sea ice has made possible.

China has been catching flack from critics who say its plans to build coal plants in developing countries along Belt and Road are just a way to find markets for its coal companies while decarbonizing at home. And since 2013, the Chinese government has invested $50 billion to build overseas coal projects. Unless China changes course, 60 additional coal plants, emitting nearly as much carbon dioxide as Spain does each year, could come online in BRI countries.

Biden also called out China’s BRI in his climate plan for “financing billions of dollars of dirty fossil fuel energy projects across Asia and beyond.”

To encourage a Chinese shift to clean-energy projects along BRI, Biden said on the 2020 campaign trail that, if elected, he would rally the rest of the world to hold China accountable for the environmental impact of its BRI and make the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies a necessary condition for starting any new US-China climate negotiations.

Instead of climate legislation, on January 27 President Biden issued an executive order asking the secretaries of State, Treasury, and Energy to work with all relevant agencies and partners of the US government to “identify steps through which the United States can promote ending international financing of carbon-intensive fossil fuel-based energy while simultaneously advancing sustainable development and a green recovery.”

The Biden administration’s strategy is to call China’s bluff on international climate leadership by leaving the country isolated in its support for overseas fossil fuel projects. Feeling the cold shoulder and already committed to addressing climate change as part of its national interests, the hope is that China would then reverse course and use clean-energy alternatives for BRI instead.

In 2020, China’s investment in renewable energy (solar, wind, hydropower) accounted for the majority of its overseas energy investment for the first time, at 57 percent — a substantial increase from 38 percent in 2019. But China’s state-owned companies and banks still largely support fossil fuel projects over renewable energy, which means there’s more room for improvement.

On February 13, noting the number of intricate steps necessary to pull off Biden’s BRI strategy, Politico reported that former climate adviser to President Barack Obama, John Podesta, said Biden’s climate strategy of isolating China as a climate hypocrite would take some “diplomatic choreography” to work.

There’s reason to believe the dance between the US and China on climate has already begun.

As the Wall Street Journal reported on March 9, the US and China are co-chairing a G20 group on the economic risks of climate change and ensuring a green recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, which means Biden’s plan to pressure China to switch to clean-energy alternatives by seeking a “G20 commitment to end all export finance subsidies of high-carbon projects” is underway, though given the tensions between the two countries, the negotiations are progressing at a slow pace.

The best approach to engaging China moving forward, Georgetown’s Lewis wrote in a recent paper, is to “leverage rather than block China’s BRI investments to support regional development needs, while simultaneously redirecting BRI toward greener technologies.”

But the Biden administration also needs to invest in clean-energy projects for lower- and middle-income countries, not just push China to do so.

One way to do that is through the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) established in 2019. And it appears for the Biden administration, that work is already underway.

While naming future priorities for DFC’s work at a DFC board meeting March 9, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said “development finance is a powerful tool for addressing the climate crisis.”

Blinken said he and Kerry are “very interested in how the DFC can help drive investment toward climate solutions, innovation in climate resilience, renewable energy, and decarbonization technologies.”

On March 18, in a display of DFC’s commitment to helping developing countries transition to clean energy, DFC and USAID announced $41 million in financing support for renewable energy in India. Blinken also said that Biden’s climate summit of world leaders on April 22 would be a chance to put DFC’s work on display.

Climate responsibility begins at home, but it has worldwide impact

The US alone can’t finance all the clean-energy projects needed to make renewable energy more attractive to developing countries than China’s coal investments in BRI. But it can send a strong message to China and the rest of the international community by finally contributing to international climate funds established under the Paris Agreement.

In 2014, then-President Barack Obama promised $3 billion for the Green Climate Fund, an international initiative that has committed nearly $8 billion since 2010 to help developing countries address climate change by tying the money to “low-emissions and climate resilient development.” But by the time Obama left office, the US still owed $2 billion.

During his term, President Donald Trump ended US commitment to the fund. But with Trump out of office, climate activists are now calling on the Biden administration to step up to the plate.

As a part of his climate platform, Biden said he will recommit the US to the Green Climate Fund. Climate envoy Kerry has also echoed that commitment. But if the US does recommit, it should also play a role in helping manage the Green Climate Fund. This would help ensure the money goes to those most vulnerable to climate change, as recent claims about Fund mismanagement have surfaced.

The US may also become a first-time donor to the Adaptation Fund, which has raised $783 million to help developing countries prepare for climate change impacts.

The Biden administration is very much aware of its responsibility to help developing countries transition to net-zero economies. During remarks on January 25 at the virtual Climate Adaptation Summit, Kerry promised the Biden administration would “make good” on past promises.

“Internationally, we intend to make good on our climate finance pledge,” Kerry said.

While noting that in the long term the best way to help developing countries address climate change was transitioning to net-zero by 2050 and limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, Kerry said the Biden administration will “significantly increase the flow of finance, including concessional finance, to adaptation and resilience initiatives.”

There’s no better way to signal that “America is back” on the world stage than for the US to become more active in development finance for countries in need of help. If enough countries increasingly prefer renewable-energy projects, it could pressure China to reconsider its overseas investment in fossil fuels.

There’s already evidence to suggest this is happening. On March 10, the Financial Times reported that China decided to cancel its coal projects in Bangladesh, citing concerns about pollution.

At this point, there’s also significant support among American voters for US-China cooperation on climate change, so it’s just a matter of summoning the political will to make ambitious plans a reality. Recent polling by the Asia Society Policy Institute and Data for Progress indicates that a majority of likely American voters (56 percent) think the US should work with China to address climate change, setting aside disagreements on other issues to end the emergency.

Though the two countries had a combative first meeting in front of cameras on Thursday, there are still plenty of ways both sides can work in tandem, if not together, to address climate change.