An expert told Vox that Biden team’s idea is a “Hail Mary pass.”

After weeks of sensitive deliberations and closed-door meetings, the Biden administration watched this weekend as two secret Afghanistan documents leaked to the public — revealing their behind-the-scenes push for a peace agreement between the Taliban and the Afghan government that would facilitate the withdrawal of US troops from the 20-year war.

Until the leak of these documents, the belief was that the Biden administration was discussing three broad options for how to proceed in Afghanistan.

The first was to adhere to former President Donald Trump’s deal with the Taliban, which would require President Joe Biden to withdraw all remaining 2,500 US troops in the country by May 1. The second was to negotiate an extension with the insurgent group, allowing American forces to remain in the country beyond early May and likely pressuring the Taliban to reach a peace agreement with the Afghan government. And third was to defy the Trump-Taliban pact altogether and keep US troops in Afghanistan with no stated end date.

But two documents published by Afghanistan’s TOLONews show the Biden administration may be seeking a different path: One that pushes for an accelerated peace and, potentially, sets the stage for a troop withdrawal by the end of the president’s first term — a promise he made during the campaign.

In an undated letter from Secretary of State Tony Blinken to Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, the top diplomat informs Ghani that the Biden administration is “immediately pursuing a high-level diplomatic effort” to “accelerate peace talks” between the Afghan government and the Taliban. To that end, Blinken says the administration has prepared a “roadmap for the peace process.”

The second leaked document is that roadmap: an eight-page “discussion draft of a peace agreement” designed “to jumpstart Afghanistan Peace Negotiations between the Islamic Republic [of Afghanistan] and the Taliban.”

The proposal has three sections: 1) guiding principles for Afghanistan’s constitution and the future of the Afghan state; 2) terms for governing the country during a transitional period and a roadmap for making constitutional changes and addressing security and governance matters; and 3) terms for a permanent ceasefire.

“The draft reflects a variety of ideas and priorities of Afghans on both sides of the conflict and is intended to focus the negotiators on some of the most fundamental issues they will need to address,” the US proposal reads. But, it adds, “Ultimately, the two sides will determine their own political future and the contours of any political settlement.”

Zalmay Khalilzad, the US envoy for Afghanistan, reportedly presented this plan to the government in Kabul and the Taliban last week. “Ambassador Khalilzad’s trip represents a continuation of American diplomacy in the region,” a State Department spokesperson said. However, they added, “We have not made any decisions about our force posture in Afghanistan after May 1. All options remain on the table.”

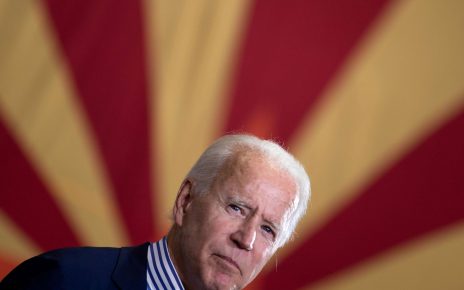

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22354457/1275336294.jpg) Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesExperts say the US may have two goals in mind with this play. Should both sides agree to this or a similar peace plan by May 1, Biden would have the political room to withdraw all troops from the country. Or, if there was genuine movement toward a deal but no agreement, Washington would let the Taliban know it was going to stay until the group struck a deal.

“This gives them the space to argue it both ways,” said Jonathan Schroden, an expert on the war at CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization in Arlington, Virginia. But, he noted, the chances that the gambit succeeds are pretty slim. “This is a Hail Mary pass.”

Simply put, it’s hard to believe long-sputtering negotiations will kick into high gear with just weeks to go before the deadline, and so far neither side has shown much appetite for the American proposal.

“They can make a decision on their troops, not on the people of Afghanistan,” Afghan First Vice President Amrullah Saleh said on Monday. “It is under discussion [and] after discussion, we will have a position on it,” said Mohammad Naeem, spokesperson for the Taliban’s political office in Doha, Qatar.

The Biden administration is pushing a high-risk, high-reward option that may still result in keeping US troops in harm’s way beyond the May 1 deadline. It’s unclear it’ll pay off.

What the two Biden documents on Afghanistan actually say

The two US-drafted documents are clearly meant to be read in tandem. The proposal lays out a draft agreement meant to spur talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban, while Blinken’s letter establishes an international diplomatic framework to support an agreement.

It’s worth taking a quick look at the key elements in the documents.

Blinken’s letter sets up a framework for international diplomacy

In his letter, Blinken says the US plans to ask the United Nations to bring together nations with interests in Afghanistan — the US, Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan, and India — to hash out what each party would like to see in a peace deal. “It is my belief that these countries share an abiding common interest in a stable Afghanistan and must work together if we are to succeed,” the secretary writes.

It’s a smart initiative that experts have long called for, analysts told me, but they fear it’s too much, too late. It’s a process that should’ve begun years ago, and getting so many disparate parties aligned on such a complicated matter likely won’t happen by May 1.

One matter highlights that point: Afghanistan is wary of cutting any deal with Pakistan since it’s long been a supporter of the Taliban, and Pakistan would rather Afghanistan remain unstable than move any closer to India. Should Kabul and New Delhi become very friendly, Islamabad fears it’d be surrounded by two antagonistic partners.

Then add in how the US, Iran, and China feel about the situation, and it becomes clear that these talks could take a while to complete.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22321493/1229709795.jpg) Patrick Semansky/AFP via Getty Images

Patrick Semansky/AFP via Getty ImagesOrganizing such a gathering, then, “is just step one in a journey of 1,000 steps,” said Adam Weinstein, a former Marine who served in Afghanistan and is now at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a Washington-based think tank the advocates for military restraint in US foreign policy.

Blinken’s letter also says the US plans to ask Turkey to host “a senior-level meeting of both sides in the coming weeks to finalize a peace agreement.” This sounds like a new version of the US-brokered 2001 Bonn conference that appointed a transitional government in Afghanistan, which is why some analysts told me they’re already calling the proposal “Bonn 2.”

Here again, the problem is the timeline, as the government in Kabul and the Taliban until May 1 to finalize a peace deal.

Reaching an agreement during that time frame is possible, experts say, but not likely, considering all the complicated issues they must discuss. That’s where America’s peace proposal comes into play.

The US-drafted peace plan is specific but full of tough asks

The document Khalilzad showed to both parties is meant to help the warring sides reach a deal faster.

It begins by establishing a number of guiding principles meant to address the concerns and demands of both the government in Kabul and the Taliban, including that:

- Islam will be Afghanistan’s official religion

- The future Constitution will guarantee the protection of women’s rights, and the rights of children, in political, social, economic, educational, and cultural affairs

- Afghanistan will be a safe home for all of its ethnic groups, tribes, and religious sects

- The future Constitution will provide for free and fair elections for Afghanistan’s national political leadership in which all Afghan citizens have a right to participate

- The future Constitution will establish a singular, unified and sovereign Afghan state under a single national government, with no parallel governments or parallel security forces

The proposal also lays the groundwork for the creation of a transitional “Peace Government” to run the country until a new constitution is adopted and national elections held.

Critically, the Peace Government would consist of officials appointed “according to the principle of equity” between both parties, and “with special consideration for the meaningful inclusion of women and members of all ethnic groups throughout government institutions.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22354463/1206279825.jpg) Johannes Simon/Getty Images

Johannes Simon/Getty ImagesFinally, the agreement outlines the terms for both sides to come to a permanent ceasefire and how that ceasefire will be implemented and monitored. The deal would seek a 90-day reduction of violence and then create a commission to oversee the ceasefire’s continuation throughout the peace process.

There’s more in the plan, but you get the idea. What the US offered is a start — and in some areas, much more than that — but most expect it’ll take longer than a few weeks to reach the end of the process.

Hanging over it all is what the US will do with its troops. Importantly, neither document ties America’s military presence to the diplomatic effort, which means the US could remove service members from the country and still push hard to broker a deal.

Experts say that possibility runs the risk of weakening Kabul and America’s leverage during negotiations, giving the Taliban the upper hand in talks or incentive to just take over the capital city and the remaining parts of the country it doesn’t currently control by force.

But some also say tying America’s troop presence to a highly complex process is also problematic, since it would leave service members in danger for an unknown period of time.

“A sustainable agreement cannot be predicated on the permanent presence of US troops,” said Weinstein. “The small chance that a political settlement is reached exposes the Biden administration to considerable risk. It’s the equivalent of gambling.”

Tough decisions, then, are to be had not only in Afghanistan over the next couple of weeks, but also in Washington.