It’s not clear that the president’s decision was legal.

President Joe Biden is facing heat from fellow Democrats and law experts over his Thursday airstrikes against targets in eastern Syria tied to Iranian-backed militias, namely because they say he had no real legal justification for the attack.

The administration said the seven 500-pound bombs dropped on facilities two militias used to smuggle weapons were designed as a message: Attack US troops in the region and you risk retaliation. Over the past two weeks, Iranian proxies have fired rockets at anti-ISIS coalition forces outside Erbil, Iraq — killing a Filipino contractor and injuring US troops — and near the US Embassy in Baghdad.

“President Biden will act to protect American and Coalition personnel,” Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby said in a statement hours after the strikes, calling them a “proportionate military response.” As of now, no deaths have been confirmed — the Pentagon is still assessing that — though US officials said they suspect the strikes possibly killed a “handful” of people.

Congressional Democrats denounced the strikes almost immediately, saying the US is not at war with Syria and that lawmakers didn’t authorize any attack on Iranian-backed militants. As a result, they essentially argue Biden ordered an illegal launch.

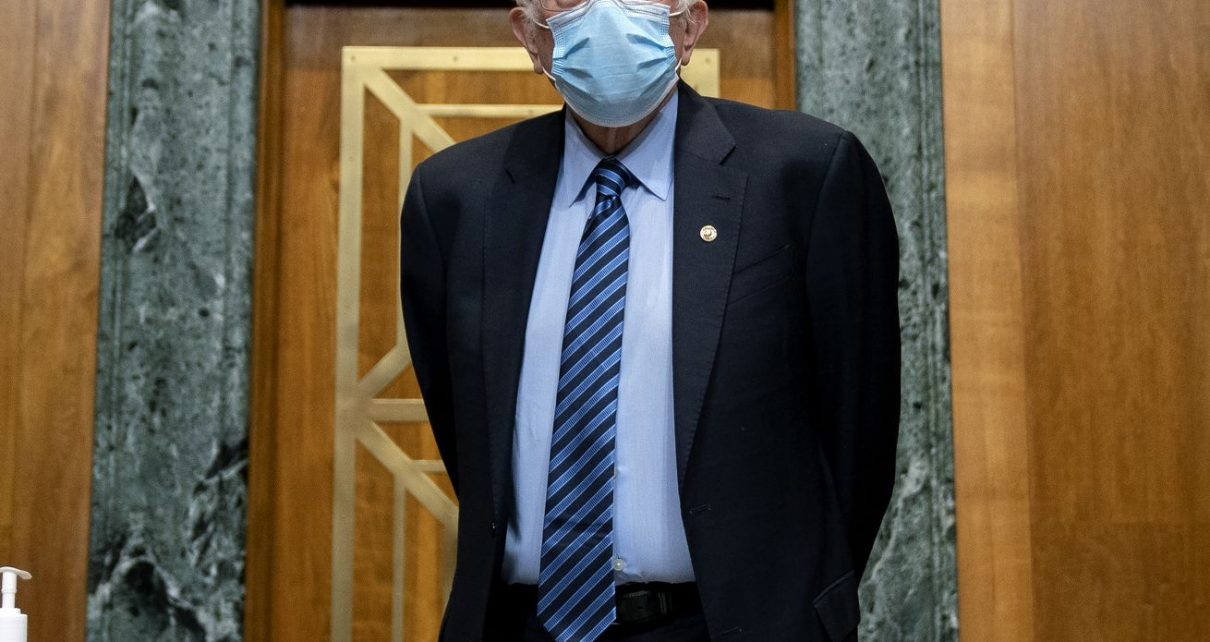

“Offensive military action without congressional approval is not constitutional absent extraordinary circumstances,” Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA), a longtime advocate for bolstering Congress’s role in authorizing military operations, said in a Friday statement. “Our Constitution is clear that it is the Congress, not the President, who has the authority to declare war,” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) added on Friday.

Criticism continued in the House. Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), a leading progressive foreign policy proponent, stated, “There is absolutely no justification for a president to authorize a military strike that is not in self-defense against an imminent threat without congressional authorization.”

Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-MN) also highlighted a 2017 tweet from current White House press secretary Jen Psaki that criticized then-President Trump’s decision to bomb Syria in retaliation for a chemical weapons attack. “What is the legal authority for strikes?” Psaki asked, noting “Syria is a sovereign country.”

“Good question,” Omar tweeted in response on Thursday night.

Great question. https://t.co/79K8uyzwGi

— Ilhan Omar (@IlhanMN) February 26, 2021

Vice President Kamala Harris, then a senator, also questioned Trump’s 2018 bombing of Syria after another chemical weapons attack, tweeting, “I am deeply concerned about the legal rationale for last night’s strikes.”

While many Republicans showed their support for the attack, the pushback over Biden’s first known strike reflects a decades-long debate over what the president can and can’t do with the largest military in the world. Biden’s decision in Syria just provided the latest flashpoint.

It’s therefore worth looking at each side’s main arguments. They’ll dominate not only the discussion about this strike but future ones over the next four years, too.

The Syria strikes reanimated the presidential vs. congressional war powers fight

A National Security Council spokesperson told me the administration has two main legal arguments for why Biden had the authority to retaliate against Iranian-backed proxies operating on the Syria-Iraq border. Both of them rely on the idea that responding to the last two weeks’ attacks on coalition facilities counts as self-defense.

Regarding domestic law, the spokesperson said, “the President took this action pursuant to his Article II authority to defend U.S. personnel.” Simply put, Article II of the Constitution names the president as the commander in chief, thereby giving him ultimate authority over all military matters.

US troops were endangered by the proxies’ actions in recent weeks, and so he had every right to defend them from future attack, the argument goes. Importantly, the White House isn’t claiming it had the authority to drop bombs on Syria, just that the US had a pressing need to act in self-defense.

As for international law, the spokesperson said “the United States acted pursuant to its right of self-defense, as reflected in Article 51 of the UN Charter.” That article states, in part, that nothing in the UN’s laws “shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations.” (We’ll come back to the full first sentence in a moment.)

By citing this provision, the administration is basically making the same argument as it did in domestic law: The proxies threatened US troops, and so America has the right to use force to defend them.

Congressional Democrats (and some Republicans) aren’t buying those arguments, though. Their case, based mostly in domestic law, stems from Article I of the Constitution, which states that only Congress can declare war or authorize military operations. There are some situation-dependent caveats to this, but that’s the main point.

Over the decades, Congress has abdicated that authority, rarely taking war votes while allowing the president to wield the military as he sees fit. The Korean and Vietnam wars, for example, were conducted without congressional approval. And the 2001 authorization passed to greenlight operations against al-Qaeda after 9/11 continues to be cited for counterterrorism operations around the world, even when al-Qaeda wasn’t the target.

Lawmakers have slowly begun to claw back their authority. In 2019, Congress passed a “War Powers Resolution” to block Trump from involving the US military in Yemen. Trump vetoed the bill, however, and without the supermajorities needed to overrule that veto, those offensive operations continued until Biden stopped them earlier this month. Still, it was a signal that Congress would rise against a president abusing his legal mandate.

Also in disagreement with Biden’s team are some law of war experts.

Mary Ellen O’Connell, a professor at Notre Dame and co-author of Self-Defense Against Non-State Actors, told me she agrees that the president should come to Congress when there is time to seek authorization. There was in this case, she contends, as the aggressions weren’t happening now but rather occurred over the past two weeks.

That’s something Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) picked up on in his Friday statement.

“Retaliatory strikes, not necessary to prevent an imminent threat, must fall within the definition of an existing congressional authorization of military force,” he said. “Congress should hold this administration to the same standard it did prior administrations, and require clear legal justifications for military action, especially inside theaters like Syria, where Congress has not explicitly authorized any American military action.”

But O’Connell’s main critique is that the White House got the international law wrong. As promised, here’s the first sentence of the UN Charter’s Article 51 in its entirety: “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.”

O’Connell said the attack wasn’t on the American homeland, and the US surely had enough time to work with UN Security Council partners to punish Iran using diplomacy — not force. That means Biden’s team either willingly misread what that provision says or didn’t comprehend its true meaning.

“They are citing the correct sources of law,” O’Connell said, but “they are wildly misinterpreting them.”

“They are undermining their attempt at becoming a leadership team for the international community in promoting good order, stability, and the rule of law,” she concluded.

Of course, the president had more than legal argument on his mind when making his decision to drop bombs. As president, it’s his responsibility to protect Americans wherever they are. He also surely didn’t want Iran to believe it could threaten US troops with impunity. Risking Congress denying an authorization request might send Tehran that exact signal.

But even Kirby, the Pentagon spokesperson, couldn’t define what imminent threat US forces faced in Syria or Iraq, except to say the Thursday attack was meant to deter future Iranian assaults on Americans.

Which means the debate over when a president can authorize a strike by himself and when he must ask lawmakers for permission is alive and well during the Biden years. It’s raging already, and will surely continue in the years to come.