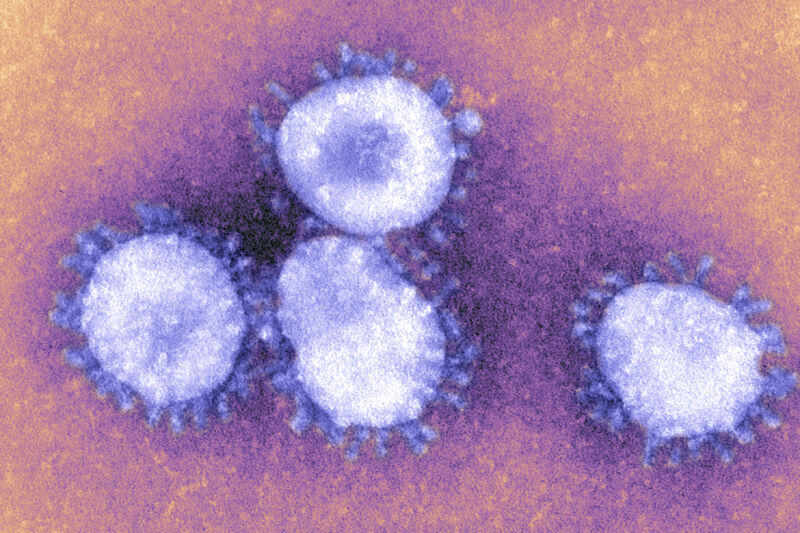

Enlarge / Coronaviruses (credit: Getty | BSIP)

Ever since the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, began jumping from human to human, it’s been mutating. The molecular machinery the virus uses to read and make copies of its genetic code isn’t great at proofreading; minor typos made in the copying process can go uncorrected. Each time the virus lands in a new human victim, it infects a cell and makes an army of clones, some carrying genetic errors. Those error-bearing clones then continue on, infecting more cells, more people. Each cycle, each infection offers more opportunity for errors. And, over time, those errors, those mutations, accumulate.

Some of these changes are meaningless. Some are lost in the frenetic viral manufacturing. But some become permanent fixtures, passed on from virus to virus, human to human. Maybe it happens by chance; maybe it’s because the change helps the virus survive in some small way. But in aggregate, viral strains carrying one notable mutation can start carrying others. Collections of notable mutations start popping up in viral lineages, and sometimes they seem to have an edge over their relatives. That’s when these distinct viruses—these variants—get concerning.

Scientists around the world have been closely tracking mutations and variants since the pandemic began, watching some rise and fall without much ado. But in recent months, they have become disquieted by at least three variants. These variants of concern, or VOCs, have raised critical questions—and alarm—over whether they can spread more easily than previous viral varieties, whether they can evade therapies and vaccines, or even whether they’re deadlier.