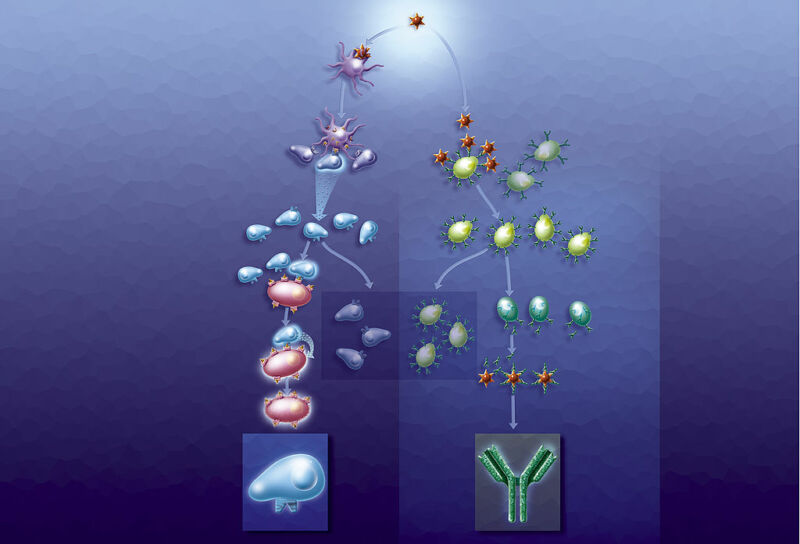

Enlarge / The immune response involves a lot of moving parts. (credit: BSIP/Getty Images)

There’s still a lot of uncertainty about how exactly the immune system responds to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. But what’s become clear is that re-infections are still very rare, despite an ever-growing population of people who were exposed in the early days of the pandemic. That suggests that, at least for most people, there is a degree of long-term memory in the immune response to the virus.

But immune memory is complicated and involves a number of distinct immune features. It would be nice to know which ones are engaged by SARS-CoV-2, since that would allow us to better judge the protection offered by vaccines and prior infections, and to better understand whether the memory is at risk of fading. The earliest studies of this sort all involved very small populations, but there are now a couple that have unearthed reasons for optimism, suggesting that immunity will last at least a year, and perhaps longer. But the picture still isn’t as simple as we might like.

Only a memory

The immune response requires the coordinated activity of a number of cell types. There’s an innate immune response that is triggered when cells sense they’re infected. Various cells present pieces of protein to immune cells to alert them to the identity of the invader. B cells produce antibodies, while different types of T cells perform functions like coordinating the response and eliminating infected cells. Throughout this all, a variety of signaling molecules modulate the strength of the immune attack and induce inflammatory responses.