When the U.S. rejoins the Paris Agreement later this year, fulfilling President-elect Biden’s campaign pledge, much of the world will be wondering the same thing, says Amos Hochstein: How serious is the U.S., really?

“We can’t walk into 2021 expecting that we’re just erasing the last four years, and the United States is walking onto the international stage, as though we’re in 2016,” says Hochstein, a national security expert who is the former Obama and Biden special envoy for international energy.

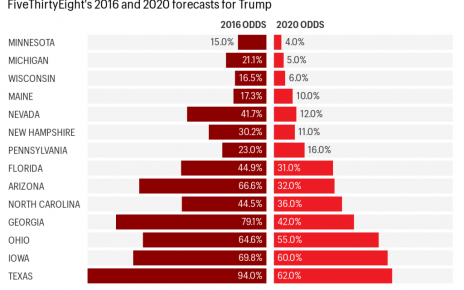

Four years of the Trump administration—which reversed much of the Obama administration’s climate policy both abroad and at home—have produced wariness internationally that a new commitment to the climate will truly have lasting support domestically, he argued, speaking at Fortune’s Brainstorm Tech virtual event on Monday.

The countries that have pushed ahead in their ambitions in the past four years—particularly in Europe, but also, notably, behemoths like China, which committed last year to hit net-zero emissions by 2060—will be watching closely and holding the U.S.’s feet to the fire to ask for real, concrete commitments, he says.

Those doubts predate the Trump administration, he added, including lasting “scars” over the Kyoto Protocol among allies, who he said regularly recalled the U.S.’s pressure on other countries to sign onto the Agreement—while support floundered back in Washington.

Those worries were cemented when many of the Obama administration’s commitments were passed by executive action, he said, and were promptly reversed by the incoming Trump government—including the Paris Agreement, which the U.S. officially withdrew from on Nov. 4, 2020, while the country was waiting for the results of the election.

Concerns over the U.S.’s capacity for lasting momentum on climate change policy isn’t limited to the international community, he argued.

While the Democrats will have the benefits of control over the executive branch as well as the House and a thin majority in the Senate—won in last week’s landmark elections in Georgia—they face other challenges: a conservative-leaning Supreme Court plus deep divisions in Biden’s own party over climate policy and the challenge of getting large swathes of America on board with the energy transition, Hochstein says.

“Making this transition more acceptable and palatable to a broader swath of the American population is going to be critical to the success of the administration,” he says.

To do so, incentives—the “carrot” in the “carrot and the stick”—and the buy-in of the business community are going to be particularly important, he says, especially as the jobs and opportunities of the energy transition won’t be spread out equally.

But rather than gain a leadership position among the group, the U.S.’s goals should perhaps be simpler: Get back in the door, and get taken seriously.

“The way we will get our seat back at the table with credibility,” he says, “is what we do at home.”

More politics coverage from Fortune:

- Supreme Court to review whether or not Mnuchin failed to distribute COVID relief to Native Americans swiftly enough

- Democrats plan to use Senate win to pass $2,000 stimulus checks

- The world is skeptical on Biden’s climate change promises, special envoy says

- These Fortune 500 companies are halting contributions to Republicans (and Democrats) in the wake of Capitol attacks

- Commentary: Tech’s underdeveloped moral compass is threatening our democracy