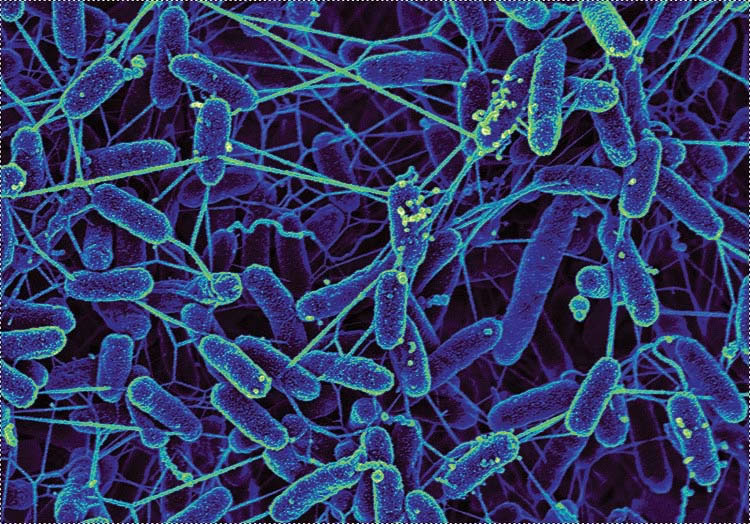

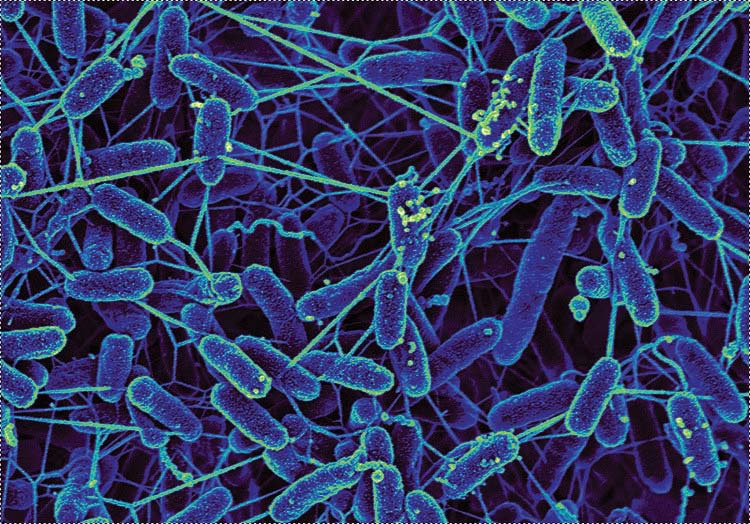

Enlarge (credit: Rizlan Bencheikh and Bruce Arey, PNNL)

In recent years, researchers have used DNA to encode everything from an operating system to malware. Rather than being a technological curiosity, these efforts were serious attempts to take advantage of DNA’s properties for long-term storage of data. DNA can remain chemically stable for hundreds of thousands of years, and we’re unlikely to lose the technology to read it, something you can’t say about things like ZIP drives and MO disks.

But so far, writing data to DNA has involved converting the data to a sequence of bases on a computer, and then ordering that sequence from someplace that operates a chemical synthesizer—living things don’t actually enter into the picture. But separately, a group of researchers had been figuring out how to record biological events by modifying a cell’s DNA, allowing them to read out the cell’s history. A group at Columbia University has now figured out how to merge the two efforts and write data to DNA using voltage differences applied to living bacteria.

CRISPR and data storage

The CRISPR system has been developed as a way of editing genes or cutting them out of DNA entirely. But the system first came to the attention of biologists because it inserted new sequences into DNA. For all the details, see our Nobel coverage, but for now, just know that part of the CRISPR system involves identifying DNA from viruses and inserting copies of it into the bacterial genome in order to recognize it should the virus ever appear again.