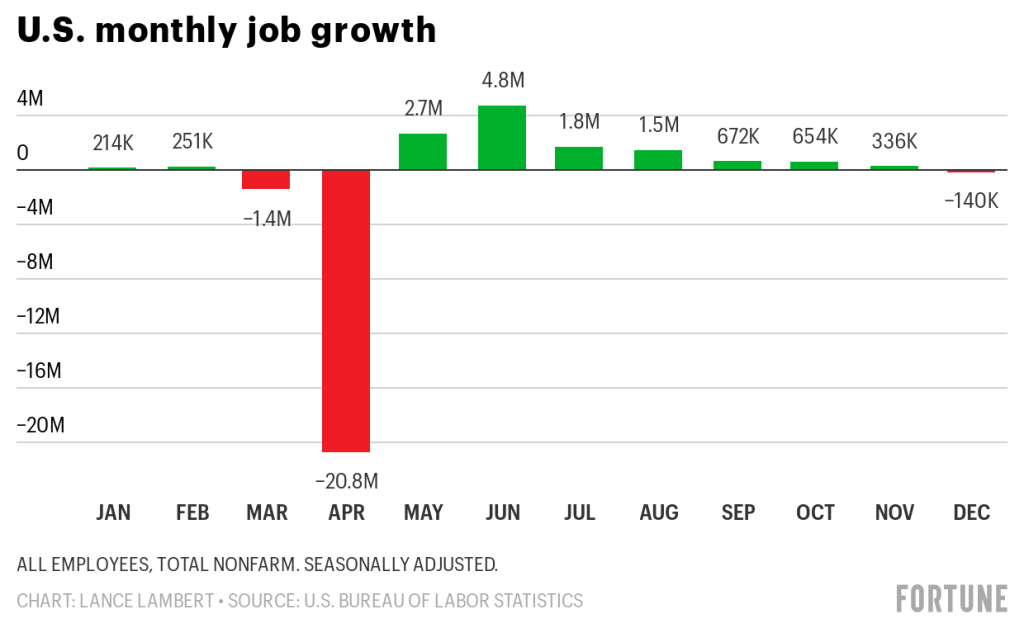

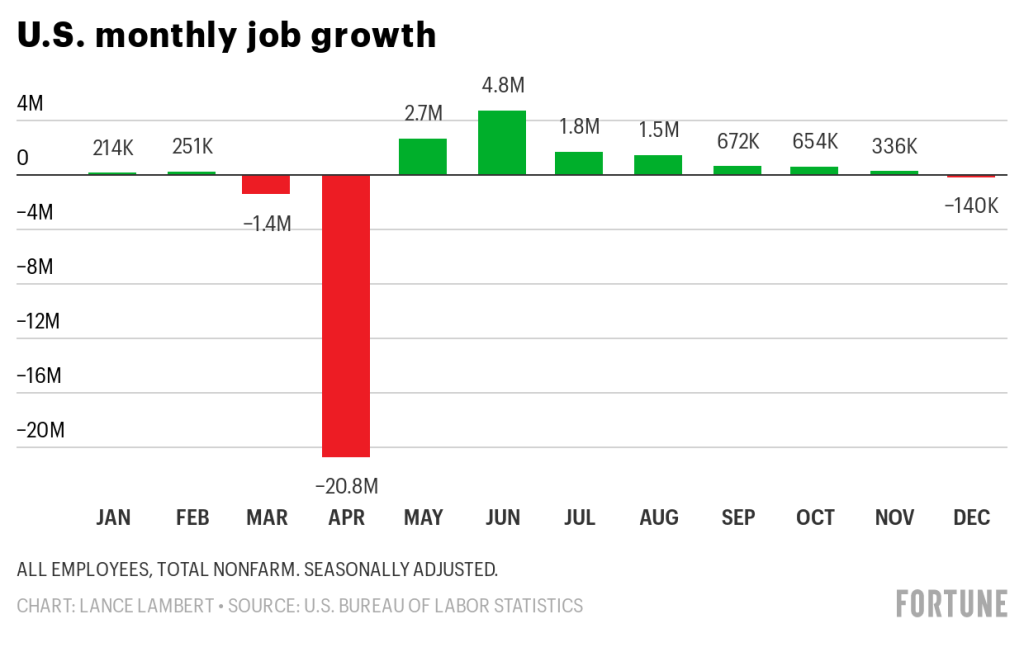

The recovery of the U.S. economy is clearly in a precarious spot.

The unemployment rate for December remained flat from November at 6.7%, and the economy lost 140,000 jobs for the month—the first monthly net loss since April.

For economists like Moody’s Analytics’ Mark Zandi, “December was a bad month for a bad year,” he tells Fortune.

Though a new $900 billion relief package is on its way, having been signed at the end of December, Zandi believes the economy will struggle for the next several months as the pandemic rages on and vaccine distribution moves at a crawl. But with the latest relief deal and the “prospect for another one on the other side of the [presidential] Inauguration, I do think we’ll avoid that double-dip [recession],” he says.

That relief from Congress appears to have come on the late side, as the Friday report shows payrolls in the hard-hit leisure and hospitality sector dropping some 498,000 (with losses of 372,000 from food services and drinking places), overall down roughly 23% from February.

And at this pace of job growth, it could be until the end of 2023 before employment recovers to the February levels, Zandi suggests.

Others like Joseph Song, U.S. economist at Bank of America, agree the labor market won’t return to pre-pandemic levels of unemployment “until sometime in 2023,” he tells Fortune. “It’s just going to be a long slog back, we’ve only recovered around 56% of job losses since March.”

A stimulus accelerant

But fresh stimulus in 2021 could help pull that timeline up, some economists argue.

“Before the Georgia Senate races, I would have said end of 2023, maybe early 2024, because I did not expect any additional fiscal support,” says Moody’s Zandi, referring to the two runoff races that turned Georgia blue on Wednesday. “But now with the Democrats controlling government, I think that pulls forward that date by a year—so I’d say the end of 2022, maybe early 2023,” he estimates.

Similarly BofA’s Song believes more stimulus (particularly something akin to President-elect Biden’s proposed multi-trillion dollar infrastructure package) could speed up the labor market recovery. (Currently Song is expecting the unemployment rate to hit mid-4% by 2022.)

That fiscal support isn’t so much relief programs like the renewed Paycheck Protection Program for small business loans meant to stem job losses, but more traditional “stimulus” packages that could spur job creation, Zandi argues. Zandi and Song both anticipate another relief package in the spring to continue to bridge the economy to the other side of the pandemic, and a fiscal package later in the year that will look like an infrastructure and social program spending package “that will get us back to full employment faster,” Zandi suggests, by creating jobs for the unemployed in infrastructure projects.

But despite the optimism that more stimulus packages are in the cards, the Democrat majority in Congress is incredibly slim, and more moderate Democrats like Sen. Joe Manchin from West Virginia could pose a roadblock to bigger stimulus.

However the $900 billion package should still provide an important boost in light of the latest unemployment figures, and despite Democratic party infighting, those like Song argue “they do know this is their one opportunity to get something done, so we do expect an additional spending package,” he says.

Ultimately, the jobs recovery depends on the virus and the vaccine. And while more stimulus will likely help speed up that recovery, BofA’s Song argues “what’s really going to let the labor market rip is getting the vaccines out and getting people back to re-engaging with the economy.”

More must-read finance coverage from Fortune:

- It’s officially a blue wave. What that historically means for stocks

- Democrats plan to use Senate win to pass $2,000 stimulus checks

- This calculator shows the “grim math” of how much leaving the workforce during COVID will cost you

- The fundamental flaw in cap-weighted index funds

- 2 U-turns in 2 days: Why the NYSE finally decided to delist 3 Chinese companies