It’s time for the world to get more ambitious with its emissions targets.

2020 was one of the two warmest years on record, tied only with 2016.

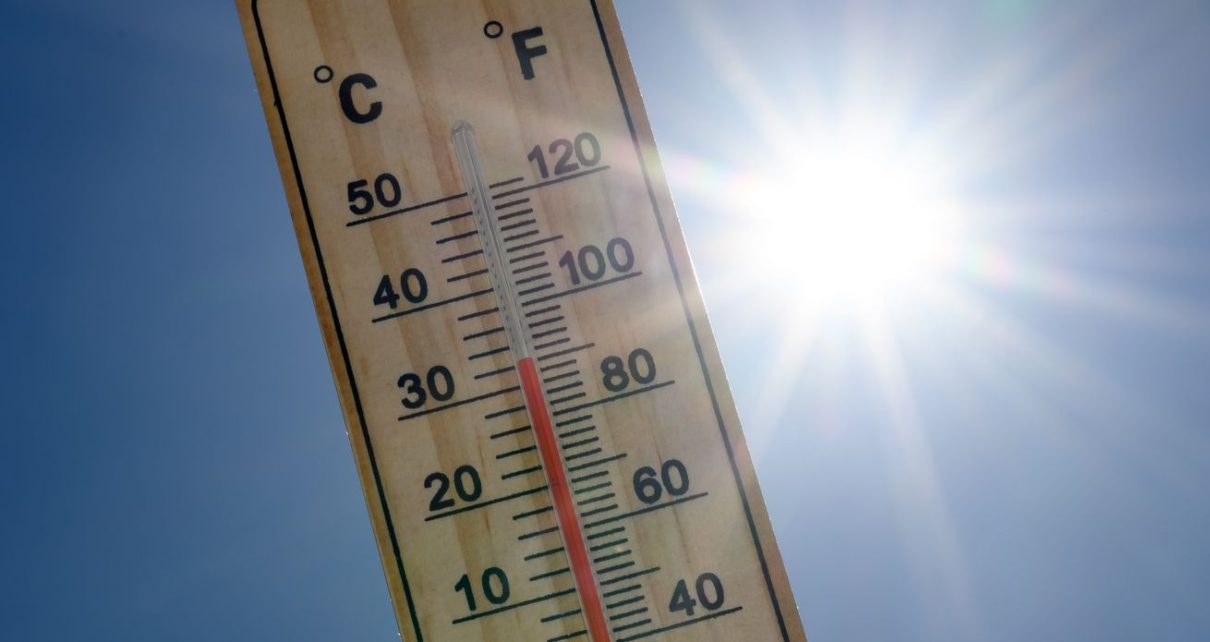

According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, in 2020, average temperatures globally were 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.25 degrees Celsius) warmer than preindustrial levels — the point at which scientists agree that human activity, and particularly the burning of fossil fuels, began to accelerate global warming.

In nearly every way, 2020 was a record year for climate-related disasters.

The impacts of the record heat have been felt both around the globe and in the United States. Historic wildfires burned in California, Colorado, Australia, and the Amazonian rainforest. The Atlantic hurricane season produced a record 30 named storms.

Swarms of crop-destroying locusts invaded East Africa, causing devastation to a region already struggling with food insecurity. The Arctic, the area that is currently warming faster than any other place on the planet, saw record declines in ice cover as well as records for how late in the year the ice actually froze.

️2020 has tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record, as well as being the hottest year recorded for Europe, according to our #CopernicusClimate Change Service.

Follow this thread for more details, or read the full press release on our website➡️https://t.co/aEj53ieM5u pic.twitter.com/qk87x1iKtg

— Copernicus ECMWF (@CopernicusECMWF) January 8, 2021

Even more troubling, 2020’s high temperatures occurred despite the absence of an El Niño event, which typically has the effect of warming the globe; 2016, the other warmest year on record, had an El Niño.

So 2020 being the warmest on record, without an El Niño event, indicates just how much human activity is changing the world around us.

Lockdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic and global traffic coming to a halt contributed to a 7 percent drop in emissions. However, the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide actually grew to record highs in May.

Recently released figures from NOAA found that more than 20 climate- or weather-related events costing $1 billion or more hit the United States last year — from a combined drought and heat wave in Colorado to hailstorms and heat waves that struck parts of Ohio.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22223231/2020_billion_dollar_disaster_map.png) Map by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2021

Map by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2021According to figures from a report by Munich Re, environmental disasters cost the world $210 billion in 2020. The US alone accounted for $95 billion of that sum, nearly double the cost of damage in 2019.

Limiting warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, the fundamental goal of the Paris climate agreement, will require countries worldwide to commit to stronger targets under the carbon disagreement and make a rapid transition away from fossil fuel-intensive practices toward renewable energy.

It’s time for the world to get more ambitious with its emissions targets

The Paris climate pact, which just had its fifth anniversary, contains a mechanism for countries to make even stronger commitments.

Yet while many countries in 2020 made headlines for announcing quicker timelines for moving to net-zero emissions, a recent analysis showed that just 45 parties (44 countries, plus the EU’s 27 member states, viewed as one bloc) met the deadline to share their updated targets. That may sound like a large number, but the world’s largest emitters — the United States, China, and India — were noticeably absent from the list.

Despite the bleak global outlook, experts say it’s possible to put the US on a 1.5-degree warming path and even cut 70 to 80 percent of emissions by 2035. But achieving rapid decarbonization requires essentially “electrifying everything,” as David Roberts reported for Vox in 2017: swapping out technologies that still run on combustion, like gasoline-powered vehicles, and natural gas heating and cooling with alternatives that run on electricity, like electric vehicles and heat pumps.

The ultimate goal is to quickly replace all carbon-heavy forms of energy with cleaner ones.

President-elect Joe Biden has announced plans to rejoin the Paris agreement on day one of his presidency, but in addition to rejoining, the US will have to make a more ambitious commitment if it truly wants to lead global efforts against climate change.