A subtle celebration of the terrifying tenderness that makes life barely survivable but also makes it worth living.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum observed in contemplating how to live with our human fragility. The monumental challenge, however, is that of sculpting such trusting openness from the messy elemental vulnerability of being human, at times too tender to bear the world with all the uncontrollable invasions of its chaos and uncertainty, invasions that so often make us feel like we are about to shatter beyond repair.

To be a complete human being is to befriend the fear of fragility, intimate and menacing as it is — the work of a lifetime that begins in those most formative and fragile years when we first become aware of a world separate from ourselves, a world we must live in, a separateness we must live with, and somehow remain whole.

How to befriend that fear is what Italian artist and children’s book author Beatrice Alemagna explores with great allegorical deftness and tenderness in Child of Glass (public library) — a long-belated addition to the loveliest children’s books of its year.

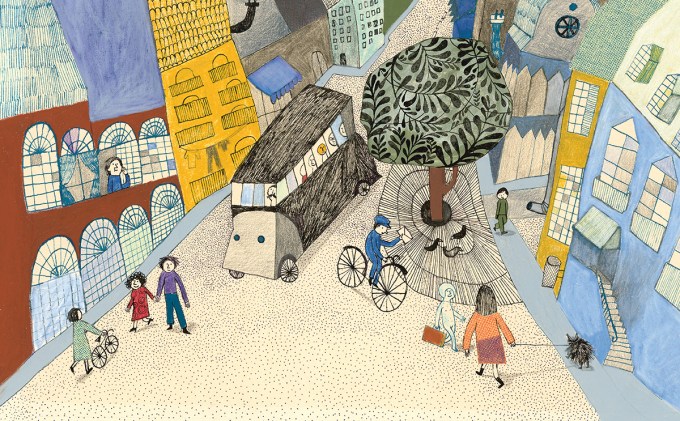

With its undertone of magical realism, the story, translated and published in English by the indefatigable Claudia Zoe Bedrick of Enchanted Lion, begins in a small European village, with the astonishing birth of a child of glass — a baby girl named Gisele.

With her large, lovely eyes, the luminous Gisele learns to live with her strange condition of total transparency, blending into the landscape and the city, changing color with the setting sun “and shimmering like a thousand mirrors beneath the moon.”

As word of this living marvel spreads throughout the village and beyond, people make pilgrimages from all over the world — to see her, to touch her, to ask the well-meaning, rude questions about whether her parents have insured her and how she can be patented.

But Gisele’s own deepest fear is not about the fragility of physical breakage — it is the savage vulnerability of being completely transparent, her inner world completely unprotected from the ceaseless invasions of the outer world, her thoughts and feelings, even the most disquieting anxieties and most private terrors, visible like a colossal ever-changing collage.

Here, the genius of the physical book, untranslatable to a screen, steps in to magnify the sensitivity of the story with a syncopation of translucent and solid pages. Transparencies of Gisele’s face layer different mood-states to render the composite confusion of her being (as we all are) half-opaque to herself but her also being (as we only imagine ourselves to be) wholly transparent to the world.

Alarmed by the visible darkness flitting across her mindscape as it flits invisibly through all of ours, the villagers turn on Gisele, begin scolding and shaming her. Unable to take the abuse, Gisele, “sparkling and luminous, sensitive and transparent,” packs her suitcase, kisses her goodbye parents, and leaves.

But wherever she goes, carrying her fragile transparency and the unbearable cargo of the attendant vulnerability, she encounters the same.

Eventually, she realizes that her only salvation lies not in changing the world’s orientation to her but in changing her own orientation to her condition, which in turn changes her interchange with the world.

The story resolves in a soulful reminder that there is no cure for our fragility — there is only the courage of not merely living with it but embracing it as a wellspring of the tenderness that makes life worth living.

Couple Child of Glass, the touching and tactile loveliness of which the screen only diminishes, with Alemagna’s wondrous illustrated celebration of the rewards of nature and solitude in the age of screens, then revisit her visual serenade to the joy of reading accompanying Adam Gopnik’s letter to children in A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

Illustration by Beatrice Alemagna courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books; photographs by Maria Popova

donating = loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes me hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most unmissable reads. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.