With the COVID-19 pandemic searing the continent with renewed vigor, Europe is back in lockdown.

But all lockdowns are not created equal, and there is massive variation in the way different European countries are tackling the surge. Some, such as France and the U.K., are shutting nearly everything they can. Others, such as Germany, are hoping a lighter touch can still turn the tide.

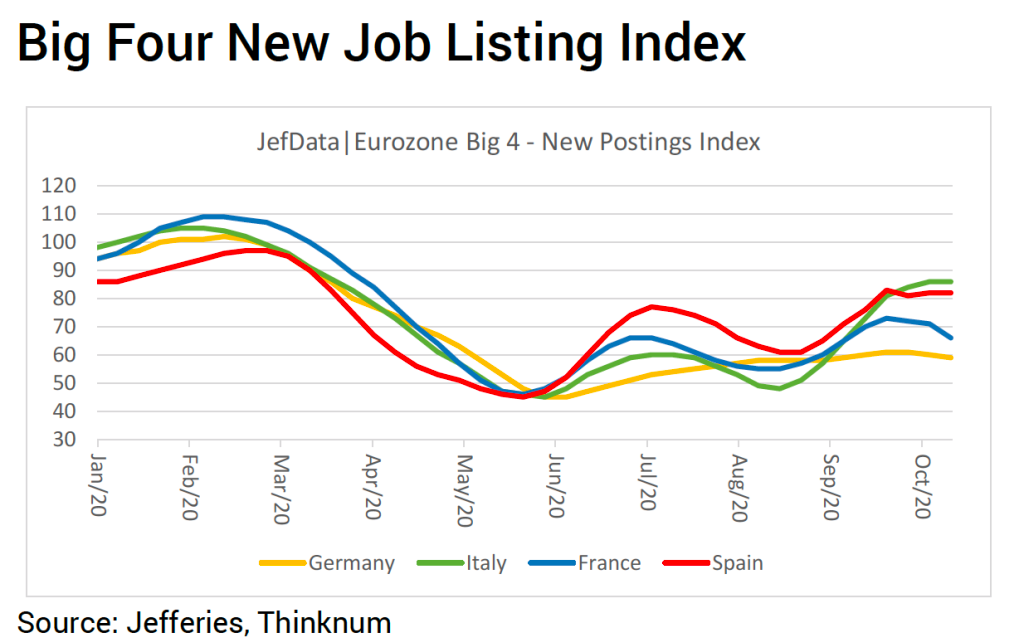

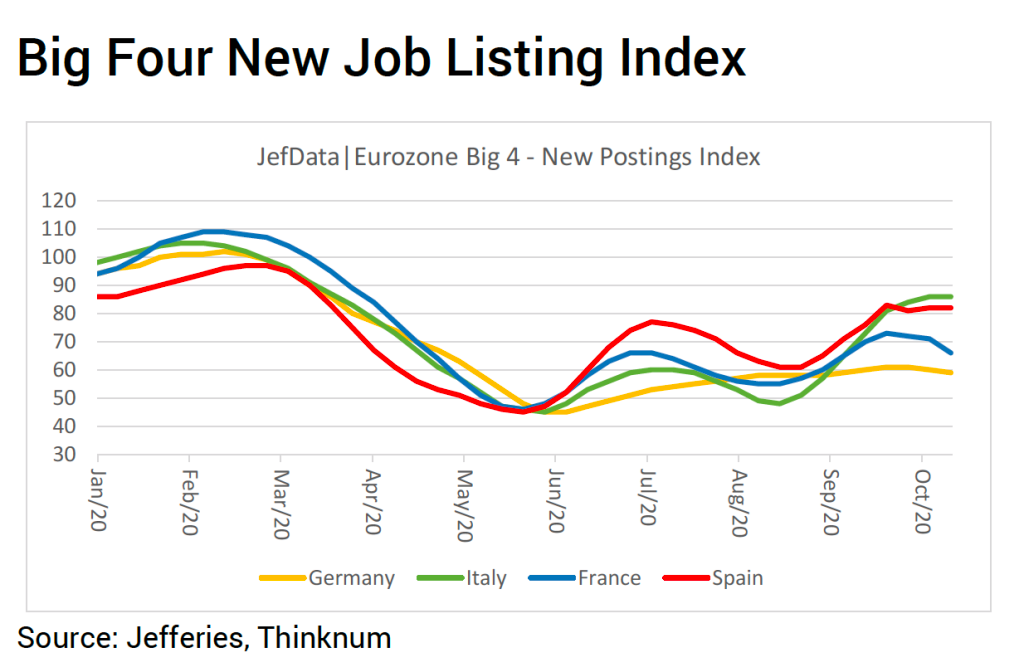

Either way, those restrictions come just as Europe’s labor markets appeared to be at least stabilizing. By October, EU unemployment was 8.1%—down from the pandemic height of 15%—but further restrictions are expected to bring another round of economic pain. On Thursday, the European Commission released a more pessimistic economic forecast for 2021 and 2022. “This forecast comes as a second wave of the pandemic is unleashing yet more uncertainty and dashing our hopes for a quick rebound,” said Valdis Dombrovskis, the Commission’s economy chief.

Here’s an examination of the situation in the three European countries where Fortune staffers live and work: Germany, Italy, and the U.K.

Germany

Germany’s second national lockdown, tentatively planned to last just through the month of November, is relatively mild. That largely reflects the fact that, while case numbers continue to rise, Germany’s current rates are below those in worse-hit neighbors—260 cases per 100,000 people over the past two weeks, versus 899 in France, 1,576 in Belgium, and 1,586 in the Czech Republic.

Nonessential shops can remain open in Germany, as long as they limit the numbers of customers inside at any given time. Gyms, sports facilities, tattoo parlors, cinemas, theaters, bars, and clubs are shut, but hairdressers get to stay open this time round, as do schools and day-care facilities.

Restaurants are getting mixed treatment in what many call “lockdown-lite”: As was the case during the easing of the spring lockdown, they cannot seat customers but they can provide takeout.

Dashmir Farizi, co-owner of the Punto e Virgola pizzeria in Berlin’s Schöneberg district, reckons that leaves him with about a quarter of his previous trade.

“It was a shock to hear that we have to close. We have been around for a decade, and to have to close is like an electric shock,” says Farizi, speaking during lunchtime on Friday, against a backdrop of upturned chairs on tables. “To lose customers in this way…It’s not easy.”

During the summer, German restaurants had to space out their tables to allow social distancing, implement various hygiene rules, and register the contact details of their patrons, but that still allowed them to maintain a semblance of normality. That’s gone now.

“Everything was perfect,” says Farizi. “The disinfection materials; tables were distanced; waiters were serving with masks. Everything was there, and despite that we have to shut. In my opinion, that’s not fair.” Department stores and supermarkets get to stay open with many people inside, he points out.

Chancellor Angela Merkel addressed just this point earlier in the week, arguing that the only alternative would be to shut everything down again.

“The answer cannot be, ‘We will keep them all open.’ That would lead to our ruin,” Merkel said. “But if people believe closing everything is more fair, it’s a possibility, but one that would be a lot harder and a lot more expensive.”

As it stands, the monthlong “lockdown-lite” will knock around half a point off German GDP, Deutsche Bank estimated earlier this month. So far, Merkel’s administration has pledged just 10 billion euros to help (mostly larger) affected businesses get through November.

“We must just try to make the best of it and all stay healthy,” says Farizi.

Italy

On Friday, Italians woke up to a country with new internal borders. To beat back a resurgent second wave of COVID cases, the government split the country into three color-coded regions: yellow, orange, and—the most restrictive—red.

The financial capital Milan, for example, is deep inside the zona rossa (red zone). Under new rules, residents of Milan and the surrounding regions of Lombardy and Piedmont cannot cross their respective borders without permission. These are the toughest measures yet since Italy in March locked down the entire country, the first nationwide COVID lockdown anywhere in the world.

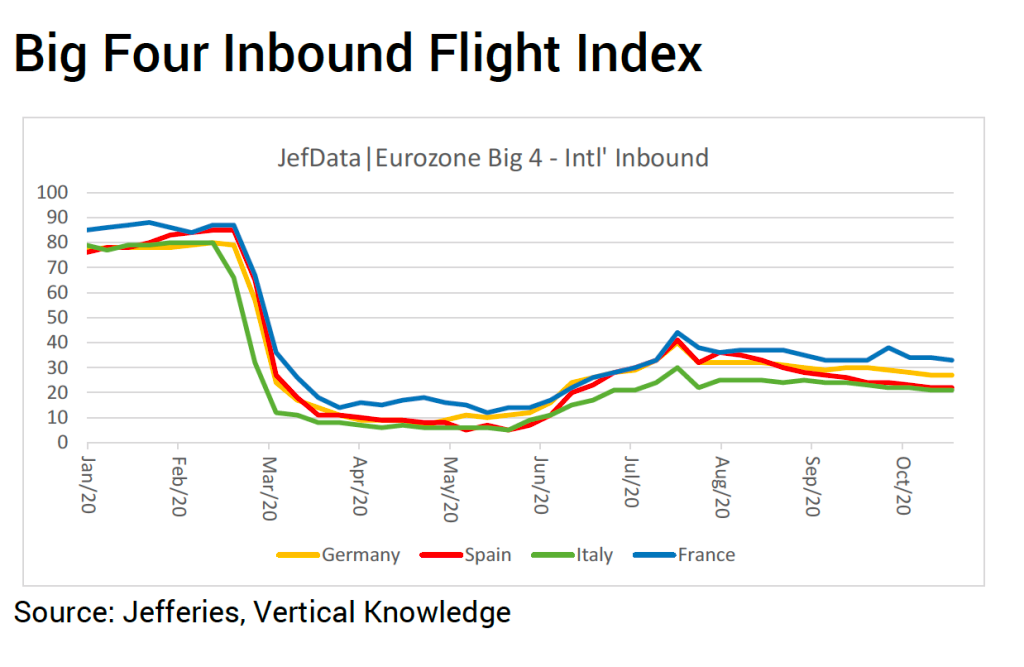

There are six such regions inside the restricted “red” area, predominantly in the hard-hit north, the heart of the Italian economy. There are growing concerns that a nasty second wave of infections could be a knockout blow for the economy. Italy’s debt-to-GDP could soar to as high as 160% next year, economists warn, as vital sectors such as tourism and hospitality collapse with fewer holidaymakers and business travelers.

You can see the impact in Rome. Museums and exhibits are closed. Restaurants and bars shut at 6 p.m., and vehicle traffic is but a trickle after dark. Local restaurateurs grumble that the promised government assistance to keep the businesses afloat is a case of too little, too late. Their big hope is that these latest measures flatten the curve in time for what’s usually a busy Christmas season.

U.K.

In the U.K., meanwhile, a fresh monthlong nationwide lockdown across England has been treated with feelings of inevitability, as restrictions had slowly tightened throughout the autumn. Lockdowns had already been in force across much of the U.K., including all of Wales and swaths of the North, encompassing Manchester and Liverpool, while the pace of infections had mounted at a rapid clip. By Friday, 1.1 million infections had been recorded in total in the U.K., with more than 23,000 infections reported on Friday alone.

Restrictions this time are slightly more mild: Schools, colleges, and some other institutions—notably, professional football—have been kept open and operating. On foggy streets in south London this week, traffic had thinned, but the sidewalks were still full of schoolchildren.

For many small businesses across London, the long period of edging toward a full lockdown has left them feeling grim but prepared; while some have made necessary tweaks, others have completely overhauled how they do business.

“We’re more prepared now,” says Adam Newey, the owner of the Hill Bakery and Deli, a small artisan bakery that also provides cheese and wine, in the south London area of Camberwell. “Our friends and customers say, ‘Well, we’ll put up with it.’”

In the first lockdown, Newey says, government support helped pay the business’s rent when it was forced to close for seven weeks. This time around, as a food business, the bakery can and will stay open. So far, footfall hasn’t been affected, he notes, and customers are still coming.

“If everyone loses their job, that might be a different story,” he adds.

For Uyen Luu, a cook and photographer, the first lockdown destroyed her business running Vietnamese supper clubs and cooking classes out of her studio in Hackney, in east London. Once restrictions were lifted, those supper clubs haven’t come back, and Luu says she’s taken a different approach: opening a Saturday-night takeaway business, relying on social media promotion, and working out of her home.

The pace has been relentless, she admits, with thin margins and high risk.

“I’m buying five times more ingredients, not knowing when people are going to order it,” she says. Like every food business, she says, the choice was adapting—or going under.

For Hayley Elam, the owner and director of the south London yoga studio Lost in Yoga, this time around is also simpler.

“We already had all of the infrastructure in place to switch everything to online yoga classes,” she says, from training the teachers to having online price packages.

But she admits she’s skeptical the lockdown will only last a month, as promised—a sign that trust, too, has worn thin in the months since the U.K.’s last lockdown.

“Last time they said two weeks, and it was 4.5 months until we reopened,” Elam says. “So it is hard to believe what the government says.”

More must-read international coverage from Fortune:

- Denmark is culling millions of furry minks to extinguish a worrying COVID-19 outbreak

- China is ramping up its other big trade war

- The world’s largest surveillance system is growing—and so is the backlash

- Who won the election? Putin and Xi, experts say

- COVID-19 resurgence sets back Europe’s economic recovery hopes