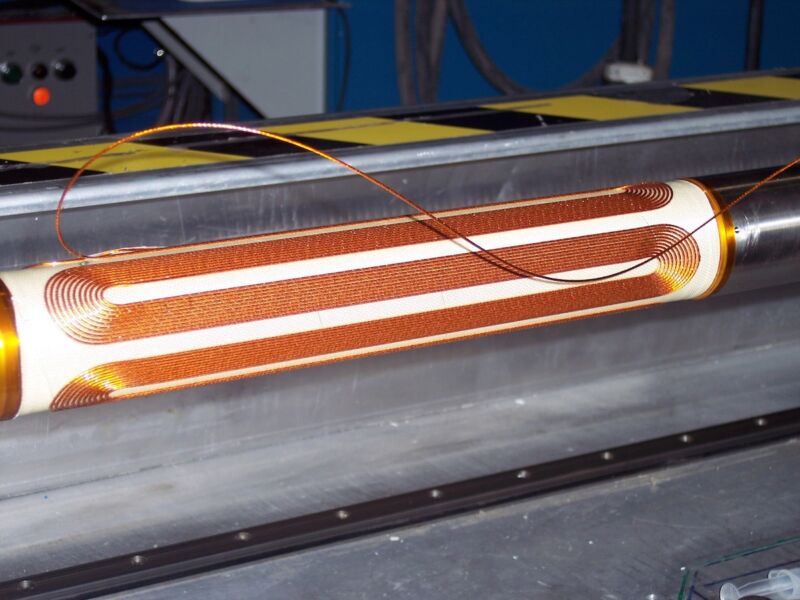

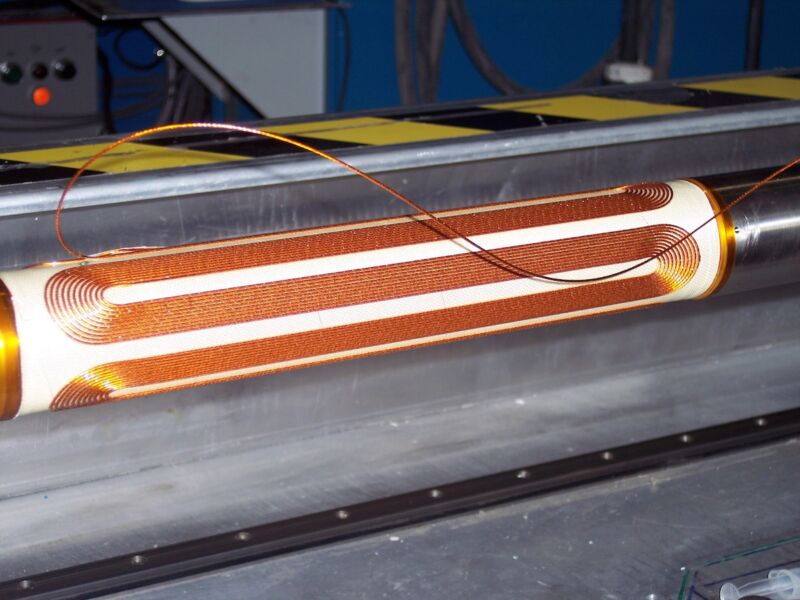

Enlarge / One of the magnets used to help contain antimatter. (credit: Brookhaven National Lab)

On Wednesday, scientists reported successfully cooling atoms made of antimatter using an ultraviolet laser. The cooling process deployed here works on normal matter, so it was also expected to work just fine with the antihydrogen used for these experiments. Rather than providing yet another confirmation that matter and antimatter appear to behave the same, the experiment is significant because it increases our chances of being able to identify subtle differences between the two types of matter.

Exotic yet apparently normal

Normal matter and antimatter are notable for their ability to annihilate each other in a burst of energy when they come in contact. But otherwise, our understanding of the physics of antiparticles indicates that they should behave identically—an antiproton can pair with an antielectron to form antihydrogen, which would then be subject to forces like gravity and electromagnetism. As far as most of physics is concerned, antimatter is just matter reflected by a mirror: a few things reversed, but otherwise identical.

Testing that, however, is a challenge. All the antimatter produced naturally on Earth comes from energetic processes like radioactive decays and the impact of cosmic rays. As a result, the antimatter itself carries plenty of energy, and it moves very quickly. Similar things apply to antimatter we humans produce. It’s generally made by colliding energetic particles with a stationary target, and the antimatter that comes out of these collisions is also very energetic.