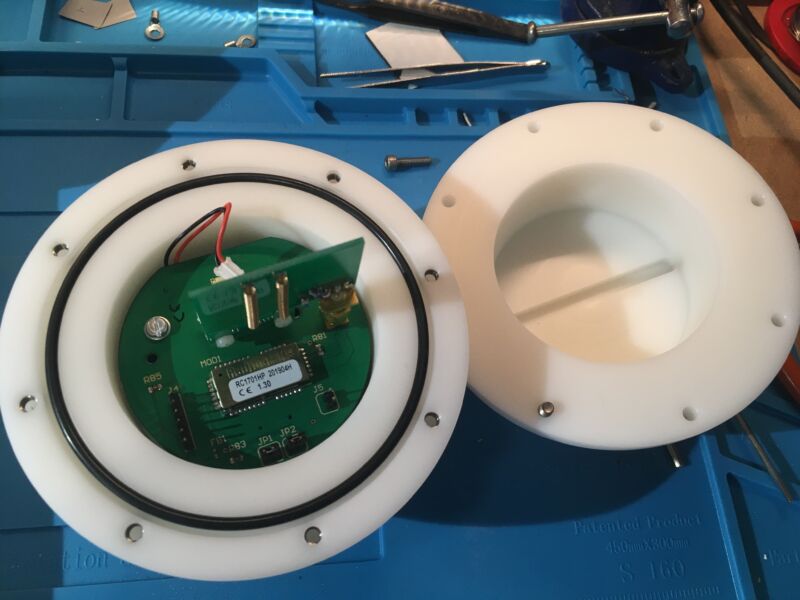

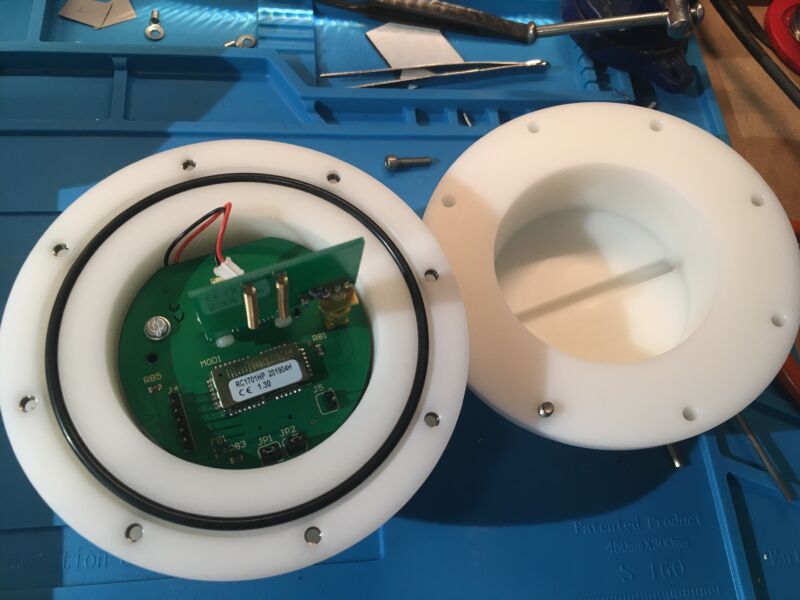

Enlarge / Sensors, support electronics, and a transmitter are all encased in a pressure-proof shell. (credit: Michael Prior-Jones)

Through the GRACE satellite program, researchers have shown that Greenland’s ice sheet has been losing about 280 billion tons of ice each year—the equivalent of close to 1.5 million Olympic swimming pools. For glaciers like those in Greenland and Antarctica, most of this meltwater ends up in the ocean—with already noticeable consequences for rising sea levels.

Better predictions of future sea level rise will require us to understand what meltwater is doing inside—and especially underneath—glaciers. But to do this, researchers need to take measurements through a glacier. Earlier this month, electrical engineer and glaciologist Dr. Michael Prior-Jones and his collaborators in the UK, Switzerland, Denmark, and Canada published their redesigned version of a wireless subglacial probe—the Cryoegg—to help study the inner “plumbing” of glaciers.

Glacial obstacles

The meltwater flowing through and underneath glaciers can end up in small pockets, large lakes, or fast-moving rivers—each of which destabilizes the overlying glacier to different degrees. Subglacial lakes can cause entire sections of the glacier to shift. By contrast, subglacial rivers channel meltwater into a smaller area, causing comparatively less glacial movement.