A humanistic love letter to who and what we are, together on this lonesome, wild, and wondrous rock adrift around a common star.

When the Voyager sailed into the unknown to take its pioneering photographic survey of our cosmic neighborhood, Carl Sagan petitioned NASA to indulge his inspired, entirely unscientific, entirely poetic idea of turning the spacecraft’s cameras back on Earth from the outer edges of the Solar System. That grainy, transcendent photograph of our “mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam” became the central poetic image of his now-iconic Pale Blue Dot meditation on our cosmic place and destiny, which in turn inspired Maya Angelou’s “A Brave and Startling Truth” — the staggering poem that flew to space aboard the Orion spacecraft, inviting a fractured humanity to reach beyond our divisive ideologies and see ourselves afresh “on this small and drifting planet,” to face our capacities and contradictions, and finally see that “we are the possible, we are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world.”

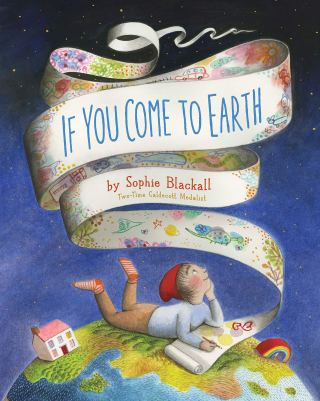

A generation later, this spirit comes ablaze anew in If You Come to Earth (public library) by Sophie Blackall — one of the most beloved picture-book makers of our time and one of those rare artists, so few in any given generation, whose work of great talent and gerat tenderness is bound to be cherished for epochs to come.

Told in the form of a letter from a child to an alien visitor — a particular child named Quinn, whom Sophie met while traveling around the world with UNICEF and Save the Children, and whose uncommon imagination fomented hers — the story is populated by drawings of other real-life children she met on her travels in India, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, a particular class of twenty-three kids she befriended in a Brooklyn public school, and her own real-life friends and neighbors. Animated by the children’s wild, wondrous, touching ideas about the most important things to communicate about our improbable, miraculous world to a visitor from another, the book radiates the spirit of the Voyager’s Golden Record — a poetic capsule of humanism and collaborative meaning-making, the true purpose of which is not to encode for some interstellar other but to decode for us who and what we are.

Page of after page, what unspools is a joyful celebration of the dazzling diversity that makes our planet a livable world: the myriad kinds of climates we live in, the myriad kinds of homes we live in, the myriad kinds of bodies we live in, the myriad kinds of creatures living alongside us, the many of them that make music — birds, whales, humans — and the many kinds of music we make.

Emerging from the story is also a quiet catalogue of the discoveries and inventions that have continually expanded the limits of our creaturely imagination, bringing us closer and closer to one another, closer and closer to the reality of this beautiful, improbable, ceaselessly astonishing planet we are fortunate to call a home: fire, music, Braille, the bicycle, air travel, medicine, the fossils the discovery of which revolutionized our understanding of evolution and deep time, the dazzling creatures of the deep sea, thought to be a lifeless world until Carl Chun’s pioneering deep-sea expedition.

Drawn into the story are curiosities that have dappled Sophie’s imagination for years, decades, a lifetime. At the tip of a promontory on a spread about the water cycle, there perches a miniature version of her Caldecott-winning lighthouse. Blazing across another spread about the unknowns of life and death is a comet inspired by a sixteenth-century illuminated manuscript.

Enchanted by the color wheel in for the forgotten vintage gem The Little Golden Book of Words, Sophie set out to paint a charming new vocabulary of colors “to paint everything in the world” — names drawn from the way colors wash our lives, the way they suffuse our remembered experience and embed themselves in the crevices of our emotional landscapes. She invited people in her world — friends, neighbors, readers — to suggest color names. Being the storytelling animals we are, this seemingly simple invitation unloosed miniature memoirs of soulful, funny, tender, profoundly human moments in human lives, concentrated and consecrated by a particular color-memory. Among those shared by readers on her Instagram — which is its own lighthouse of delight — was this story by an early childhood educator named Joey Chernila:

When I was in high school, my grandmother Nettie came to live at my father’s house. It was just the three of us. Nettie, who was immensely kind and very funny, had begun to show signs of Alzheimer’s. She always worked with her hands and was a wonderful knitter. She’d knit sweaters, scarves, and espcailly caps. Her favorite color was an unearthly pink. Somewhere between the flesh of a wild salmon and an anorak put on a child who we don’t quite trust not to run away into the woods.

As her attention span grew shorter, so too did her caps. They resembled yarmulke or the caps Marvin Gaye wore in the 70s. She could finish one in a day, and would give them out to all my teenager friends who were always about the house. Soon my small high school halls were dotted with people wearing these garishly colored tiny knit caps. Did the teachers worry that the kids were being pulled into a new kind of religious sect?

In a way, we were. Nettie would pull us aside and berate us with her fiercely humanist maxims. Chief among them was this:

Just be a human being.

We got to hear that one a lot, because she didn’t know if she had told us that before and was old enough to not really care too much. Anyway… “Nettie’s Cap” is a nice name for a color.

And so Nettie’s Cap became one of “the colors you need to paint everything in the world,” perched on the edge of the page just below the burnt-orange of Mars, opposite the forlorn algae-green of Second Place, and several chromatic continents northeast of Slug Belly.

In her author’s afterword about the making of the book, Sophie reflects on our place in the cosmic scheme — a rocky planet orbiting a single star in a particular solar system, within a galaxy populated by billions of stars, within a known universe populated by billions of galaxies — and writes:

There are lots of things I don’t know. I don’t know if there is life elsewhere in the universe, though I find it hard to believe we are alone. But I do know this: Right this minute, we are all here together on this beautiful planet. It’s the only one we have, so we should take care of it.

Complement If You Come to Earth with the story of how the Golden Record was born and astronomer Natalie Batalha, who led NASA’s Kepler search for habitable worlds outside our solar system, reading and reflecting on Dylan Thomas’s poignant cosmic serenade to the wonder of being human, then revisit the stunning drawings of the nineteenth-century scientist who coined the word ecology to weave the wildly diverse lives of our planet into a delicate tapestry of interbeing.

Illustrations courtesy of Sophie Blackall; photographs by Maria Popova

donating = loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes me hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most unmissable reads. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.